Blog

Sexual corruption is abuse of power – and there’s more to it than ‘sextortion’ alone

In December 2023, Resolution 10/10 was passed at the 10th Conference of States Parties to the UNCAC, focusing on gender and corruption. As highlighted in previous blogs, this is the first resolution to specifically mention sexual corruption. It calls on states to recognise and raise awareness about the fact that demanding sex or acts of a sexual nature can be considered a particular form of corruption. It also calls on states to take further measures and close legislative gaps in order to prevent and prosecute sexual corruption effectively.

To move forward in policy implementation, we need a shared understanding, and a new definition, of what constitutes sexual corruption.

An inclusive definition of sexual corruption

We propose an inclusive definition of sexual corruption that acknowledges several hidden aspects of the issue and emphasises the abuse of entrusted power:

Sexual corruption occurs when a person abuses their entrusted authority to obtain a sexual favour in exchange for a service or benefit that is connected to the entrusted authority.

Three components must be present for an act to qualify as sexual corruption:

- Abuse of authority: Power is abused by someone with entrusted authority for personal gain.

- Quid pro quo/This for that: A service or benefit connected to the entrusted authority is conditioned on a favour.

- Sex as a currency: The currency of the transaction is a sexual favour.

This framing of sexual corruption focuses on the responsibility of the person with entrusted authority to carry out associated duties in a just and fair manner. Our definition broadens the focus of sexual corruption to include all forms of abuse of entrusted power for sexual gain. An act can be considered sexual corruption regardless of whether the service is a right or an undue advantage, if it is extortion or bribery, and regardless of who initiated the exchange.

However, although it is vitally important to recognise sexual corruption, in reality it is not always easy to do so. And even when it is recognised, the abuse of power – inherent in this type of corruption – is a central dynamic that often goes unnoticed.

In 2019, for example, a client service agent was fired from the Swedish Public Employment Services for offering an internship to a job seeker on the condition that she have sex with him. Following his dismissal, his trade union sued his former employer for wrongful termination. In the Labour Court, he contended that he merely sought a relationship with the job seeker.

The Court found that the agent had sexually harassed the job seeker and broken the rules of his former employer, and therefore had not been wrongfully dismissed. When investigating the sex involved, the court scrutinised the actions of the job seeker to judge if she had consented to the sexual advances or not.

One aspect that disappeared in the proceedings was that the agent had abused his entrusted authority. He had conditioned a service – an internship – that was available to him by virtue of his position, on a sexual favour.

This – the abuse of entrusted power for private gain – is corruption. And there are several aspects to it that feed into our definition of specifically sexual corruption.

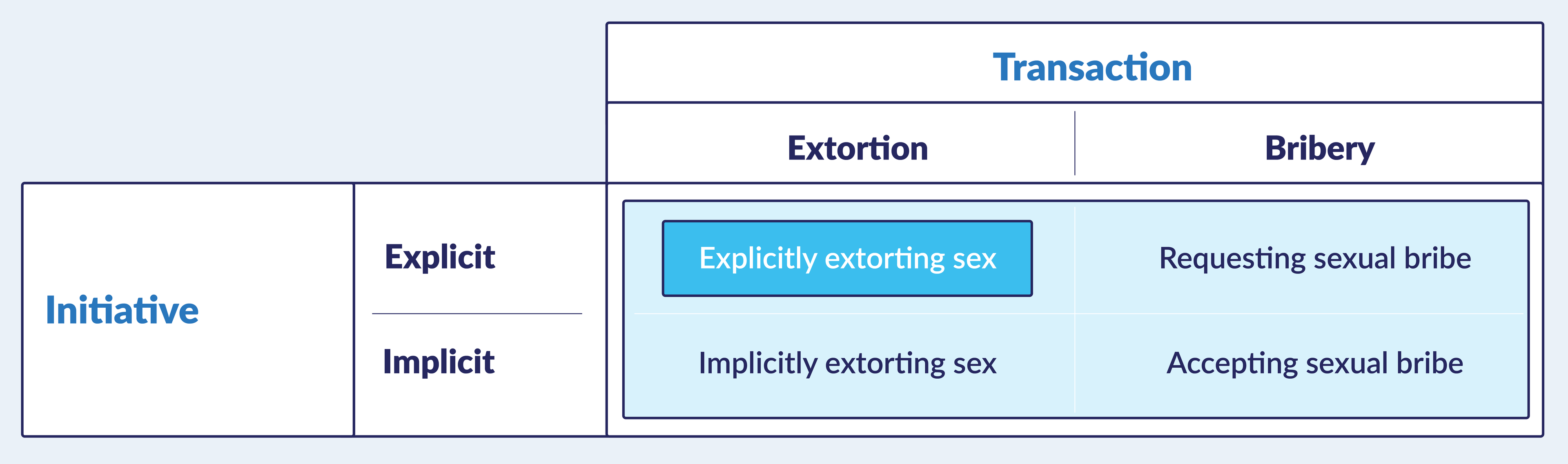

Sexual corruption includes both extortion and bribery

The word ‘sextortion’ has often been used to describe the whole phenomenon of sex and the abuse of authority (the bright-blue box in Figure 1), but because explicitly extorting sex is only one of the forms that corruption can take, we prefer to use the term ‘sexual corruption’ in our definition. For instance, if a teacher withholds something that belongs to a student by right (eg a grade or diploma) unless the student agrees to a sexual act, that is sexual extortion (sextortion). Or if a teacher offers an undue advantage (eg a higher grade) in exchange for sex, that is sexual bribery. Both cases are forms of sexual corruption: the teacher is abusing their entrusted authority for private gain, in the form of sexual favours.

Figure 1. Abuse of authority in sexual corruption

Credit: Adapted from Bjarnegård et al., 2024. copyrighted

Sexual corruption can be implicit and institutionalised

Sometimes, sex can be offered in exchange for a service because it is expected or implied. Sexual bribes can be institutionalised to the extent that they do not need to be explicitly requested. This does not change the fact that conditioning a service on a sexual favour constitutes abuse of power. Sexual corruption includes all cases of abuse of entrusted power in exchange for sex, regardless of who took the initiative and regardless of whether or not sex was explicitly demanded.

Sex as a currency in corrupt transactions

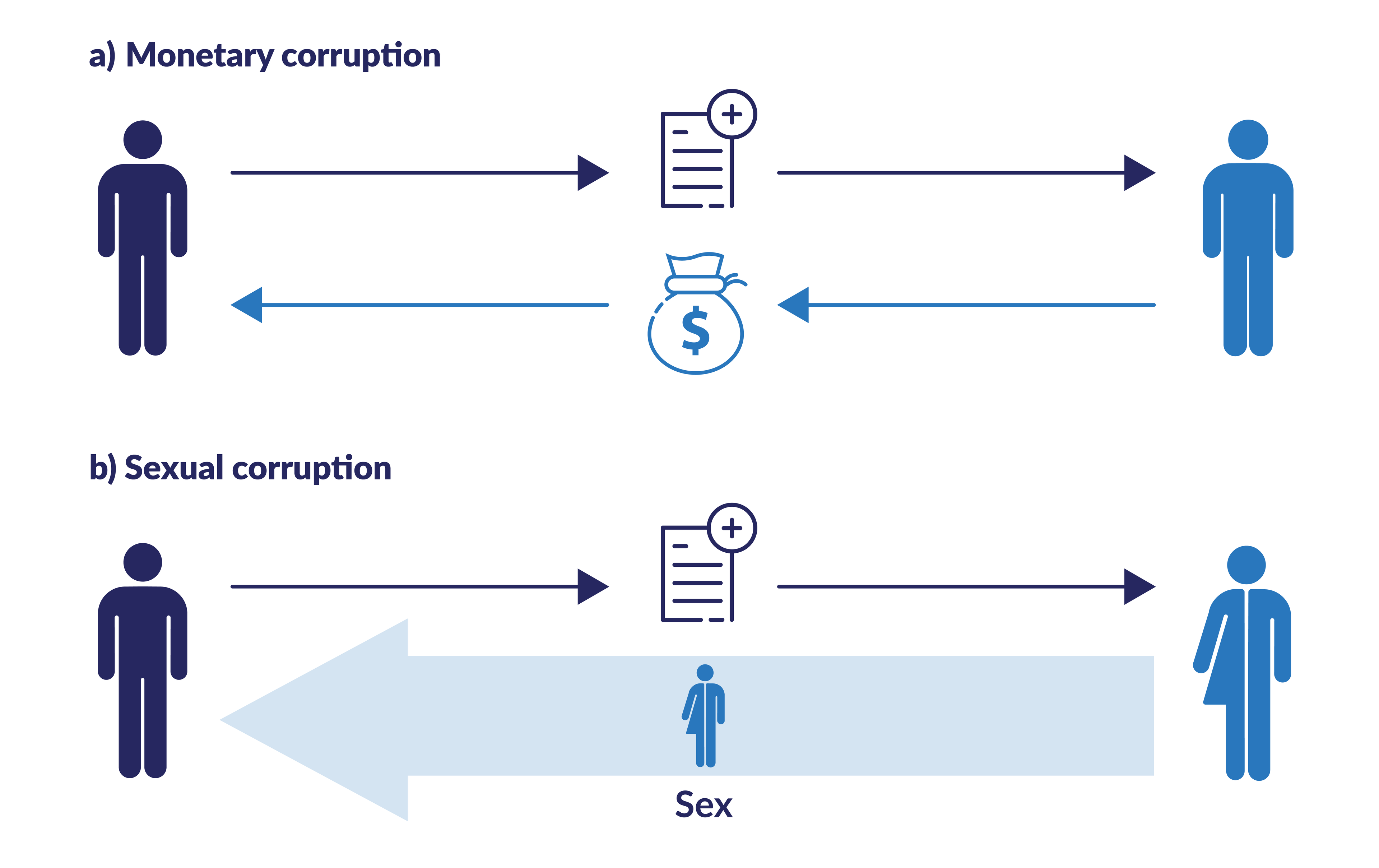

Sexual corruption is, on the surface, similar to other forms of corruption. If a border control agent demands sex to let someone cross a border, the ‘bribe’ has the same function whether it is in the form of money or a sexual favour.

But if we look a little deeper, when sex is the currency of the bribe it becomes a very different form of corruption. In monetary corruption (scenario a in Figure 2), the currency of the bribe is separate from the person paying the bribe. In sexual corruption (scenario b), the body of the service-seeker is the bribe: the bribe (sex) is inseparable from the person paying it.

Figure 2. Exchanges in monetary corruption and sexual corruption

Credit: Adapted from Bjarnegård et al., 2024. copyrighted

This has a number of implications. First, sexual corruption violates the bodily integrity of the service-seeker. It does physical and psychological harm similar to other forms of sexual violence. Second, the exchange cannot be interpreted as consensual. In sexual corruption, the sexual act is conditioned on the delivery of a service or benefit. Conditioned sex is not consensual sex.

Accountability and liability for abuse of entrusted power for sexual gain

Once we acknowledge that sex can be a currency in corrupt exchanges, we also need a stronger focus on the responsibility and accountability of the person abusing their position of authority. Legislation that recognises sexual corruption as a specific form of corruption is still scarce, but there are some exceptions, for instance Tanzania’s 2007 Prevention and Combating of Corruption Act (PCCA). Section 15 on monetary bribery holds both parties liable, while Section 25 on sexual corruption only holds liable the person abusing their position of authority, not the service-seeker.

Focus on the abuse of entrusted authority

To understand sexual corruption, we must start with – and firmly hold on to – the abuse of entrusted authority. Common expressions such as ‘sex for grades’ or ‘sex for jobs’ imply that sex is the starting point of the exchange. If we turn the expression around and instead talk about ‘grades for sex’, ‘jobs for sex’, or – as in the earlier example – ‘internships for sex’, things look quite different. The starting point of the exchange becomes the grade or the job that lies in the hands of the person with entrusted authority by virtue of their position. This shifts the focus towards the person abusing their entrusted authority, power, and position, handing out services in an unethical, arbitrary, and unprofessional manner.

All forms of abuse of entrusted power in exchange for sexual gain constitute sexual corruption. If we centre on the abuse of power, we can steer away from tired tropes that focus on the actions of the victim (eg ‘women sleeping their way to the top’). Instead, attribute responsibility where it is due: to the person abusing their entrusted power.

References

Bjarnegård, E., Calvo, D., Eldén, Å., Jonsson, S., Lundgren, S. 2024. Sex instead of money: Conceptualizing sexual corruption. Governance, 1–19.

The Swedish Labour Court. 2021. Judgment No. 10/21, Case No. A 37/20, 2021-03-10. The Swedish Labour Court, Stockholm, Sweden.

The authors form a knowledge hub about sexual corruption at Uppsala University.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)