Blog

Zero tolerance of corruption in international aid: how a scaled approach can bolster anti-corruption

From principle to practice: strict or proportionate approach?

Many countries have a policy of zero tolerance for the misuse of funds from their international aid budget. The aim is to show that corruption is unacceptable: organisations that fail to prevent it will be held responsible and face the costs.

As a general rule, the Norwegian practice is to freeze funding to organisations or programmes they suspect of corruption, and then to carry out a full investigation. If the organisation has misused funds, they have to be repaid.

Not all donors are as strict in putting the zero-tolerance principle into practice. While some countries stop all funding as soon as there is a report of misconduct, others will reduce or only partly freeze funding. This ‘lighter-touch’ or more proportionate response recognises that:

- The total suspension of funding may hurt vulnerable recipients. This would conflict with the ‘do no harm’ principle.

- In areas with extremely high levels of corruption, donors need to use a practice that is more proportionate to the severity of the alleged offence.

- Individuals or groups may invent charges of corruption. They could be trying to stop organisational reforms. Or they may wish to block funding to organisations that criticise a government or influential people and networks.

- Aid freezes can stop efforts to report on and understand the scope of the corruption, how it is organised and who is (or is not) involved. Some people argue that a more proportionate application of the zero tolerance principle could lower the threshold for reporting suspicions of corruption.

Unequal practice

Several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have called attention to what they regard as unequal treatment. While NGOs encounter immediate reactions to reports of wrongdoing, UN organisations and international development banks receive more lenient treatment — even in cases of major corruption.

The explanation is that UN organisations, the World Bank, other development banks and multi-donor trust funds have a delegated legal responsibility to investigate and deal with cases of corruption. However, on several occasions, donors have had to use pressure to get UN organisations and others to start an investigation. Donors also face difficulties finding out the results and/or ensuring that necessary changes are made.

Such unequal practices may undermine respect for the zero-tolerance principle. This is especially the case when individuals or organisations involved in documented corruption cases face no or only limited penalties or sanctions.

A scaled approach — step by step

From our discussions with aid agencies, we have learned that they wish to defend the principle of zero tolerance. Corruption is unacceptable and all those responsible should be held accountable. However, we have also found that it is possible to apply this principle in a way that still observes the ‘do no harm’ principle. This would at the same time strengthen anti-corruption efforts.

To do so, donors need to use a scaled approach, one that is flexible about the degree to which they respond to corruption. Under this method, donors also need to give additional support to measures that help manage corruption risks. This approach could lead to more cases of corruption being reported, including instances where corruption is only suspected. This would in turn strengthen the partner organisation’s own skills and capacity to identify, limit and stop corruption.

For a scaled method to work, and to be accepted by donors and fund managers, partner organisations must admit to facing risks and potentially having a problem with corruption incidents. They must also declare and show their willingness to tackle the problem.

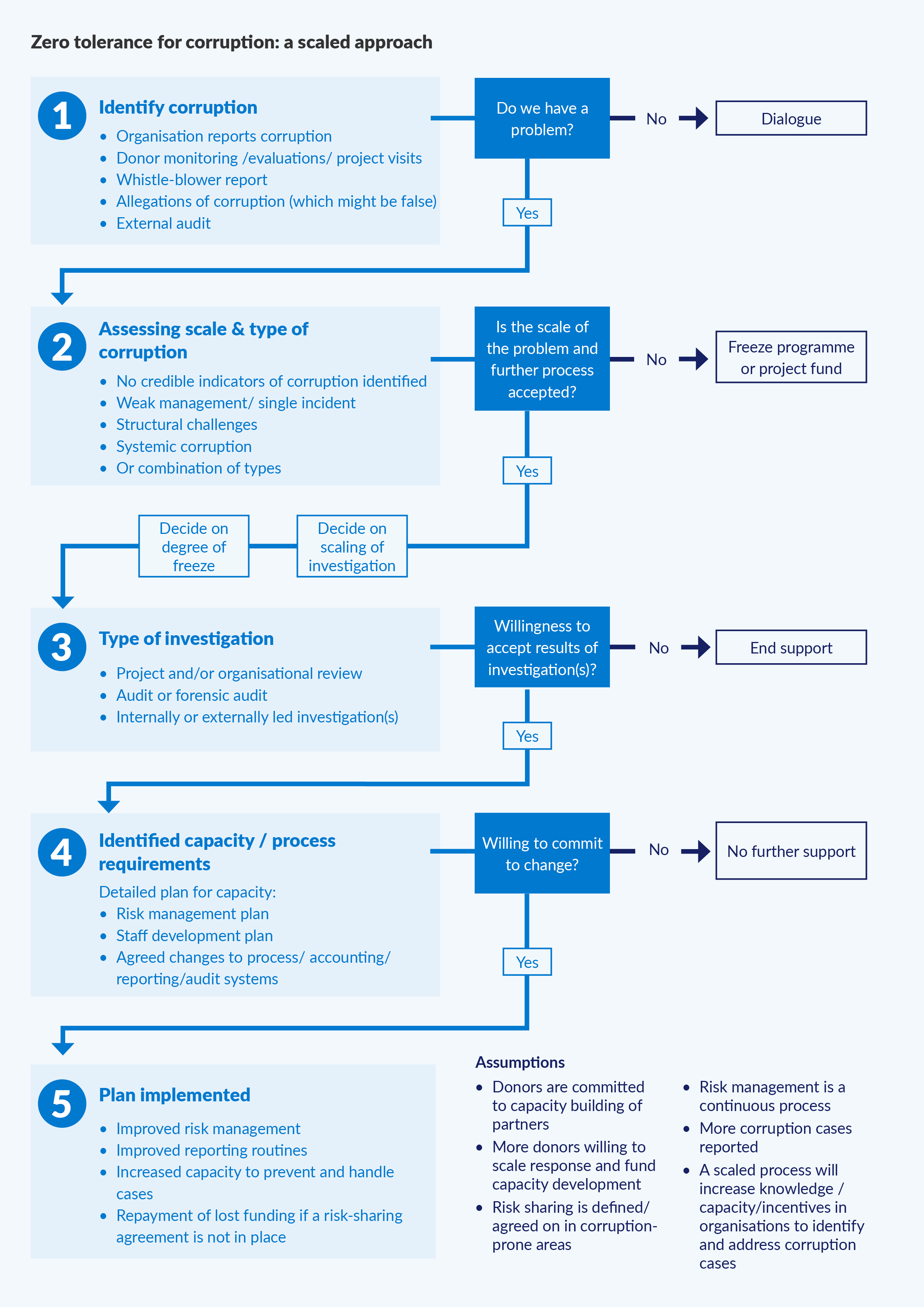

The first step then is to identify and/or admit an alleged or suspected corruption incident (step 1, see graphic). Based on existing evidence on the nature of the problem, the second step (2) would be to assess the scale and type of corruption. If credible indicators for corruption were identified, a third step (3) would be to set the scale of the investigation and the degree to which the organisation’s funding should be frozen. Investigators should judge early on if the problem is only a minor bookkeeping error, sloppy routines or false reporting. Or whether or not it is a systemic problem with many people involved and requiring a major investigation. Donors would then be able to adjust their response along the way, if the problem turns out to be larger or smaller than they first believed.

Following the investigation, it is essential that the partner organisation accepts the findings and sees how much of a problem it faces, eg single incident or more structural problem, or somewhere in between. If the organisation denies that any corruption exists or refuses to follow a plan to prevent it from happening again (step 4), its funding should be stopped. It has had its chance and has not made use of it.

Where organisations are willing to participate in a process of reflection and change, however, donors should consider granting additional funding. At this stage it is important to recall that the occurrence of corrupt practices tends to involve more than “just” financial issues, including nepotism, serious conflicts of interests or weak organisational governance. Thus the additional donor support could provide the organisation with an opportunity to improve its operational and governance systems, as well as their routines, to better guard against future corruption (step 5).

Better reporting and skills

This kind of scaled approach would avoid organisations fearing punishment if they report that corrupt practices might be taking place. It could also boost their own skills to uncover and prevent corruption. At the same time organisations can build a culture that promotes and rewards anti-corruption routines.

Shared risk

In some countries, corruption is so widespread and deep-rooted that running aid operations is a high-risk activity. By adopting a shared, scaled response to corruption cases, donors can make an active choice to share risk with partner organisations. This would also establish a shared basis for changing attitudes and improving practices.

In many cases, different donors fund the same organisations that carry out the practical work of development. A common policy and platform such as the scaled approach will add to their strength, because they will have similar information to draw on. The same applies when following up on corruption cases with multilateral organisations and national authorities.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)