1. Introduction

Vietnam has pioneered payment for forest environmental services (PFES) interventions in Asia since 2008. For around a decade, Vietnam’s implementation of PFES has typically been viewed as successful in achieving forest protection, poverty reduction and water security goals.01c708e474d6 In 2020, 46 provinces with more than 500,000 households participated in PFES, of which over 80% were ethnic minority households. Total payments for forest environmental services reached 16,758 billion Vietnamese dong (VND) up to 2019 (equivalent to US$750 million), accounting for just over 18% of total government support to the forest sector. Forest areas receiving payments for forest environmental services increased from around 1.4 million hectares (ha.) in 2011 to over 6.8 million ha. by 2020.b4526deadeb3

Several factors have, however, challenged PFES in Vietnam. One set of issues relates to the payment system. Distributing PFES payments in cash is inefficient and risky since it involves cash being transported to remote mountainous areas in large amounts. Since 2018, an electronic payment mechanism for PFES has been introduced by the US Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Vietnam Forest and Delta Program (VFD Phase 2) to tackle the risks associated with cash. The first VFD-supported e-payments via Viettel Pay were made to 530 households in Son La province and 1,951 households in Lam Dong province.d23c8e73ab66 This e-payment mechanism was viewed as promising, and 19 provinces then adopted the system in 2021. In theory, this payment method is more efficient, secure and transparent than cash, reducing transaction costs and streamlining payments. A potential additional benefit is that e-payments could reduce corruption, including embezzlement and local elite capture.

This Brief presents evidence from field research on whether, and under which conditions, PFES e-payments help to reduce the potential for corruption in benefit distribution. Our aim is to contribute to the further improvement of PFES management and sustainability in Vietnam, and to examine current issues challenging the success of the PFES e–payment system. We adopted a mixed-methods approach, including a literature review, 42 key informant interviews, 6 focus groups with PFES stakeholders, and a survey of 120 forest owner households across 3 provinces.ccece6273ed5 The findings and policy suggestions presented here are based on three provincial cases of PFES implementation in the districts of Thuan Chau and Quynh Nhai in Son La province, the districts of Don Duong and Lac Duong in Lam Dong province, and the districts of Nam Dong and A Luoi in Thua Thien Hue province.

Study sites

Box 2. Key concepts

Payments for environmental services (PES) involve a voluntary, conditional agreement between at least one ‘seller’ and at least one ‘buyer’ of a well-defined environmental service (Wunder 2007).

Corruption is defined here as the misuse of public office for private gain. The most notable examples are bribery, influence peddling, kickbacks and patronage (United Nations 2005: 23).

Anti-corruption (or anticorruption) comprises activities that oppose or inhibit corruption. Just as corruption takes many forms, anti-corruption efforts vary in scope and strategy.

Financial technology such as ‘mobile money’ is believed to improve the privacy, transparency, traceability and security of disbursements (Thompson 2017).

Elite capture is a form of corruption where the use of public resources is biased to benefit a few individuals of perceived superior social status, to the detriment of the broader population (Persha and Andersson 2014).

2. What is PFES and how should it work in Vietnam?

The notion that ecosystems provide ‘services’ that can be compensated for financially grew out of utilitarian framings in the late 1970s of the benefits of ecosystems to societal life.590c8f036e95 A popular definition stresses such payments are voluntary, conditional agreements between at least one ‘seller’ and at least one ‘buyer’ for a well-defined environmental service, or the use of land presumed to produce such services.58014f2254fe A typical example is when a forest owner receives payment for the carbon-storage service a tract of forest provides. Since the 2000s, ecosystem services ideas previously confined to environmental economics literature have increasingly reached into actual economic decision-making through the promotion of market-based (or neoliberal) instruments for conservation, such as markets for ecosystem services (MES) and payments for ecosystem services (PES) schemes.fa3458c10319 Payments for forest environmental services are a subcategory of payments for environmental services.

Vietnam’s national PFES programme has seen some promising outcomes, but not without past concerns over equity and costs.8b88894e9885 McElwee et al.0b1fb1bbb756 have shown, for instance, that local PFES distribution systems in Vietnam vary considerably, ranging from shared equal-size payments to all, to payments based on who laboured the most to protect forests, to needs-based payments. Local discretion in how payments are determined has given rise to questions about the fairness of PFES disbursements.

PFES in Vietnam should work as follows. Water companies, hydropower plants, other industries and tourism firms, who benefit from forest services, collect PFES payments from utility consumers. The firms transfer these PFES payments to a Provincial Forest Development and Protection Fund (FDPF). These PFES benefits are then distributed to environmental service providers (forest owners such as plantations, households and communities) who, in return, protect the forest. About 10% of PFES payments are kept for administering the FDPF, while the rest goes to forest owners with the aim of ensuring a more stable water supply for electricity production, clean water and other environmental services for the public.

3. How might e-payments tackle corruption in PFES benefit distribution?

Anti-corruption comprises activities that oppose or inhibit corruption. Just as corruption takes many forms, anti-corruption efforts vary in scope and strategy. Anti-corruption has, in recent years, become a priority issue for the Vietnamese Communist Party, given an understanding that perceptions of corruption could fuel (and in some instances have already led to) domestic unrest.42bec51293bd Vietnam passed its first anti-corruption law in 2005 and established a National Anti-Corruption Committee in 2006.6eac71248e24 The commitment of national authorities to tackling corruption has been interpreted as linked to fears of a loss of legitimacy to the party and state.43550827d6c4 In the forest sector, corrupt and criminal actions have contributed to illegal logging in Vietnam,9e1cf2ac6ee5 with newspapers frequently carrying stories on lam tac, a compound word referring to ‘hijacked forests’.aa02518caa6c

In this context, PFES schemes are considered potentially vulnerable to corruption. Pham et al.06721f03fa2c notes corruption might occur in relation to PFES benefit distribution, with a lack of detailed guidance on how to use the money received possibly increasing corruption in villages and communities.8c62e03e1492 Past evidence, from interviews with local officials and focus groups with households,7ea89e33bb26 has revealed examples of corruption involving village management boards, including embezzlement on the part of village heads, leading villagers to mistrust local authorities’ handling of PFES funds.

The basic anti-corruption logic of introducing e-payments to PFES is that financial technology (such as ‘mobile money’) theoretically improves the privacy, transparency, traceability and security of financial disbursements. E-payments might also contribute to more efficient and predictable forms of PFES that address some of the equity concerns discussed above.969478c385c8 Since PFES payments must pass through long chains of project actors, they incur high transaction costs and are susceptible to local elite capture, embezzlement or other forms of corruption. The various characteristics of e-payments could therefore reduce at least some corruption risks in PFES benefit distribution.

4. Assessing the anti-corruption potential of PFES e-payments

PFES appears to have made a significant contribution to forest protection and development in Vietnam. The government has involved social actors through the scheme and generated about US$725 million towards forest protection between 2011 and 2019. In 2018, Vietnam’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) approved Decree No.7491/BNN-TCLN, stating that Provincial People’s Committees should direct the Forest Protection and Development Funds (FPDFs) and agencies to distribute PFES payments via the banking system or electronic payment mechanisms. Overall, the initial e-payment pilots involving Viettel Payf6b5ad5a3957 were seen as successful. One positive early finding in Son La and Lam Dong was that e-payments could be used by at least some ethnic minorities, many of whom had limited literacy.2a9c2a4eace3 Since the initial pilots, great efforts have been made to scale up e-payments. Our research indicates, however, that there exist both multiple corruption challenges for PFES overall and numerous complications in translating the anti-corruption potential of e-payments into reality. We discuss these issues below.

4.1 Transparency and participation in payment calculations and processes

K-index: A method used in Vietnam to determine the economic value of the forest and the size of PFES payments. The index is applied by Provincial People’s Committees or the management board of Forest Protection and Development Funds.

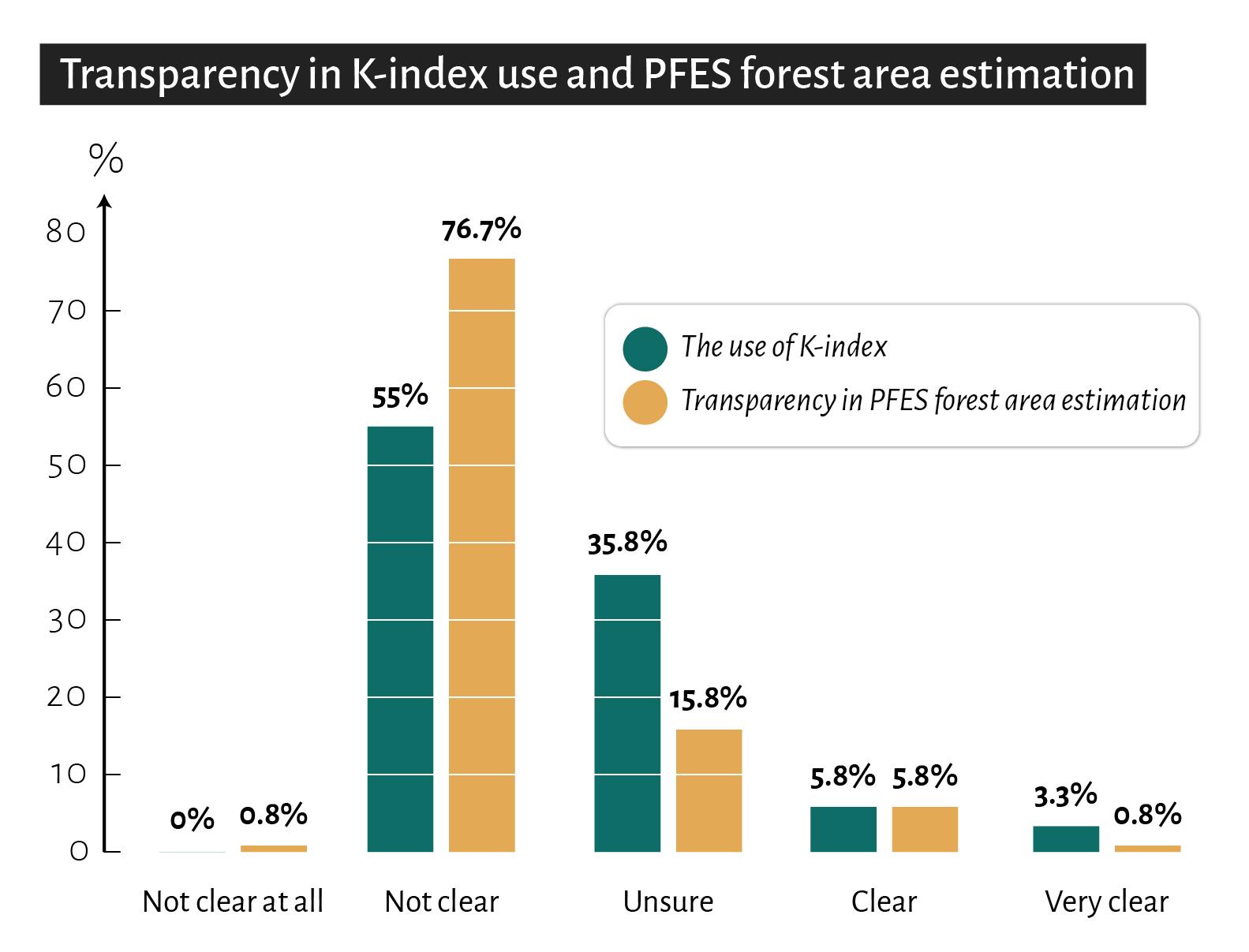

Our research points, first, to limited transparency and participation in payment calculations and processes as corruption challenges for PFES, regardless of the method of payment. Some participants in our survey said PFES payment calculations lacked transparency. When asked, for example, whether they were clear about the method for determining forest value, the so-called K-index (see box), 55% of respondents said that they were not. About 76% of respondents said they did not find the PFES forest area estimation method to be transparent. A particular concern raised was that the K-index did not appear to be sensitive to local variations in forest quality (a key determinant of the quality of the environmental services provided) and could thus lead to similar payments for different quality forest cover.

Transparency in K-index and PFES forest area estimation

Limited understanding of PFES payment calculations may not solely be the result of limited transparency of calculation methods and will relate to existing literacy and numeracy standards among forest owners. But if forest owners are unable to understand these calculations, they will also be unable to monitor the actions of village leaders and management boards. This implies any local elite capture or embezzlement that does occur is unlikely to be detectable through bottom-up monitoring. One interviewee in Lam Dong province reported that opacity in PFES payment calculations and processes had become a challenge due to limited participation of ethnic minority households:

‘We all see that a lack of participation of relevant stakeholders and information sharing have led to negative impact on effectiveness of PFES schemes in our province. You can see that all information regarding current PFES is Kinh language while about 60 to 70% of PFES forest owners are ethnic minority households.’d95df17fbc07

Despite early indications that some ethnic minority households had been able to use the e-payment method, our research found that many such households were still exposed to being taken advantage of in PFES payment calculations and processes. Some poor households, for example, were unable to calculate their forest areas using the K-index and had to ask local authorities for help. Our survey showed many ethnic minority households had lower literacy levels and few communications with officialdom. Many, therefore, found it difficult to prepare annual PFES payment requests and frequently turned to management boards, village leaders or commune officials for assistance. This reliance on third parties potentially increases the risk of local elite capture and other forms of corruption.

4.2 Continued co-existence of cash and e-payments

E-payments have contributed to reducing transaction costs for the Forest Protection and Development Funds (FPDFs). Provincial FPDFs transfer PFES benefits to bank accounts or e-wallets (e.g., via Viettel Pay) instead of physically transporting cash to rural areas. According to one public official we spoke with:

‘E-payment application for PFES benefit distribution is very helpful for us as it helps saving a lot time and transaction cost. We do not have to take PFES money to rural area as well as do not have to give cash to forest owners. We only transfer PFES benefit to their account to e-wallet of Viettel Pay. We think that it also generate transparency in PFES benefit distribution. We know some difficulties in e-payment application but not much.’a2741de9500b

But e-payments still exist alongside payments via commercial bank accounts and cash. Cash can, indeed, still change hands in relation to the determination of forest areas and their value. Our interviews with ethnic minorities participating in PFES revealed similar findings in all three provinces: forest owners living in remote and mountainous communities tended to be unfamiliar with the e-payment method. One ethnic minority PFES forest owner in Lam Dong noted that:

‘We received PFES benefit in cash from the leader of our group. It is convenient for us. We do not know much about e-wallet or banking account, which even become more complication to us. As such, it’s even more unclear to people like us, not to mention we don’t have smartphones, other services for paying with e-wallets are not available in my village.’cb374a8d3644

Another ethnic minority PFES forest owner in Thua Thien Hue said:

‘Our forest area is quite small, so the PFES benefit is not significant source to our income, it is more convenient for us to receive cash. We are not familiar with e-payments and I do not know application of PFES benefit payments to make the PFES schemes more transparent. Although we have also been trained, it is difficult to apply. The number of local adopters is small because we can choose to accept cash.’b42cd185d08e

We observed, therefore, different assessments of the usefulness of PFES e-payments from the public officials (especially those from the Forest Protection and Development Funds) as compared to the ethnic minority forest owners participating in PFES we spoke with. What is certain is that, in many locations, e-payments continue to co-exist with cash payments, leaving PFES benefit distribution open to the potential corruption associated with cash.

Our study also revealed that the leader and cashier of each community forest group were typically the only two people to receive information about PFES payments to the accounts of each group. As one interviewee reported:

‘We often know amount of PFES payment upon our labor days contribution to forest patrolling activities in the end of year. Other expenditures of PFES benefit of our group were decided by leaders. We do not know when the PFES payment made for our group. We should have information about PFES payment transferring and participating in PFES expenditures in your group.’76c91cb62d60

Further information-sharing mechanisms thus appear necessary among forest community members, forest community group leaders and the FPDFs on PFES payments and expenditures.

4.3 Limited access to devices, technological services and financial literacy

In our survey, a large proportion (73%) of respondents preferred to receive PFES payments in cash, with a smaller proportion (27%) preferring e-payments or bank transfers. One explanation for this is that despite receiving training and leaflets about the e-payment method, many forest owners lack smartphones, internet connections, access to ATMs and/or other technological services for using e-wallets. One interviewee reported that:

‘We live in the forest. We are familiar with cash-based markets rather than bank accounts or e-payments. Although we have been introduced e-payment methods, we still do not know how to use it. We prefer payment in cash to e-payment. We do not have smartphones, we do not have ATM in our village, if you want to withdraw small amount of PFES benefit, have to go to district centres. It is really an inconvenience for us while PFES benefit is decreasing annually.’6865e74bc594

Another issue undermining full application of the e-payment system is limited financial literacy among PFES management boards and village leaders. Management boards and village leaders play an important role in receiving PFES benefits for members of communities. But many are not adequately trained in financial management, while some are illiterate. Since PFES financial management regulations are quite complex, management boards face difficulties in distributing PFES benefits and preparing receipts for expenditures. One village leader in Thue Thien Hue reported that:

‘We are assigned leader of PFES forest management board of 60 PFES forest households in our village. Our management board consists of 4 persons but none of us get financial training on financial management. We have both worked and researched more regulations in the management of PFES benefit. PFES benefits usually don't transfer until December of each year, while we have to spend the whole year. The PFES money is now transferred to the bank account and the bank is located in the district center. Every time I went to withdraw PFES benefit in bank, we have to complete complicated procedures; both me and the cashier went to district for whole day but sometimes could not withdraw money. We also had difficulty preparing receipts for the purchase of equipment.’37bfb01eda65

In other words, our research found that limited access to devices, technological infrastructure and financial literacy constrained the uptake and functioning of e-payments. In turn, these conditions likely undermine the anti-corruption potential of e-payments at the community forest group and individual forest household levels – for example, by providing incentives for the continued use of cash.

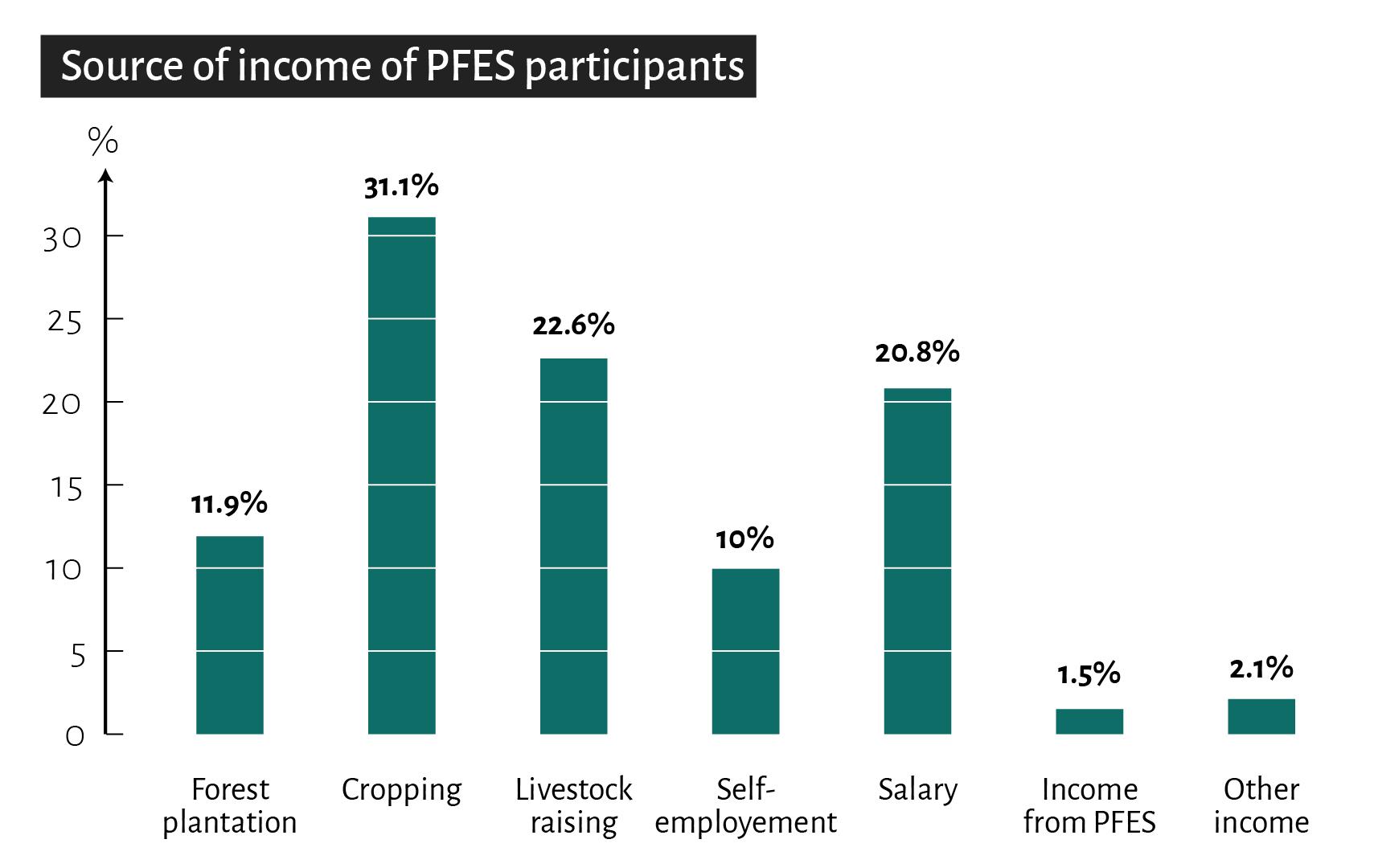

4.4 High opportunity costs for forest owners engaging in PFES

Forest owners who participate in PFES must forego forest conversion and protect forest areas. This means they cannot engage in a range of lucrative activities (some of which are already illegal) that destroy and/or degrade forests, such as corn and coffee production, shrimp farming (if it converts mangroves), or accessing timber. Yet many forest owners at the study sites we surveyed stated that PFES payments constituted only a very small share of their total annual income (about 1.5%). They therefore continued to engage in a range of other income-generating activities, as seen in Chart 2.

Source of income of PFES participants

As one forest owner in Thua Thien Hue reported:

‘We were allocated 15 hectares of natural forest for protection and participating in PFES schemes. In 2019 and 2020, we got paid about VND 100.000 to 200.000 per ha. on average (in our village). We all know any source of income is important to us. However, about VND 1.5 million does not make important changes in our livelihoods per annum. We have to practice many livelihood activities in order to make a living for my family.’c2b77f79c1c3

The opportunity costs for forest owners participating in PFES are therefore high and this may challenge forest owners’ incentives to protect forests under the PFES scheme. One public official in Lam Dong noted that:

‘In fact, there are still some issues affecting the implementation of PFES […]when the income from PFES only accounts for a small proportion of the income of forest owners. When participating in PFES […], forest owners must make commitments not to encroach on forests and must participate in forest protection and development. Meanwhile, many social actors in the region still encroach on forest areas to grow coffee and vegetables and reap great benefits. This affects the psychology of PFES forest owners.’95ba8003fd70

Observing their neighbours benefitting economically from forest conversion could lead some forest owners participating in PFES to convert forestland into coffee or rubber plantations, or to other uses. Some forest owners might conceivably also participate in PFES while still engaged in illegal logging, although we did not find concrete examples of this during our research.

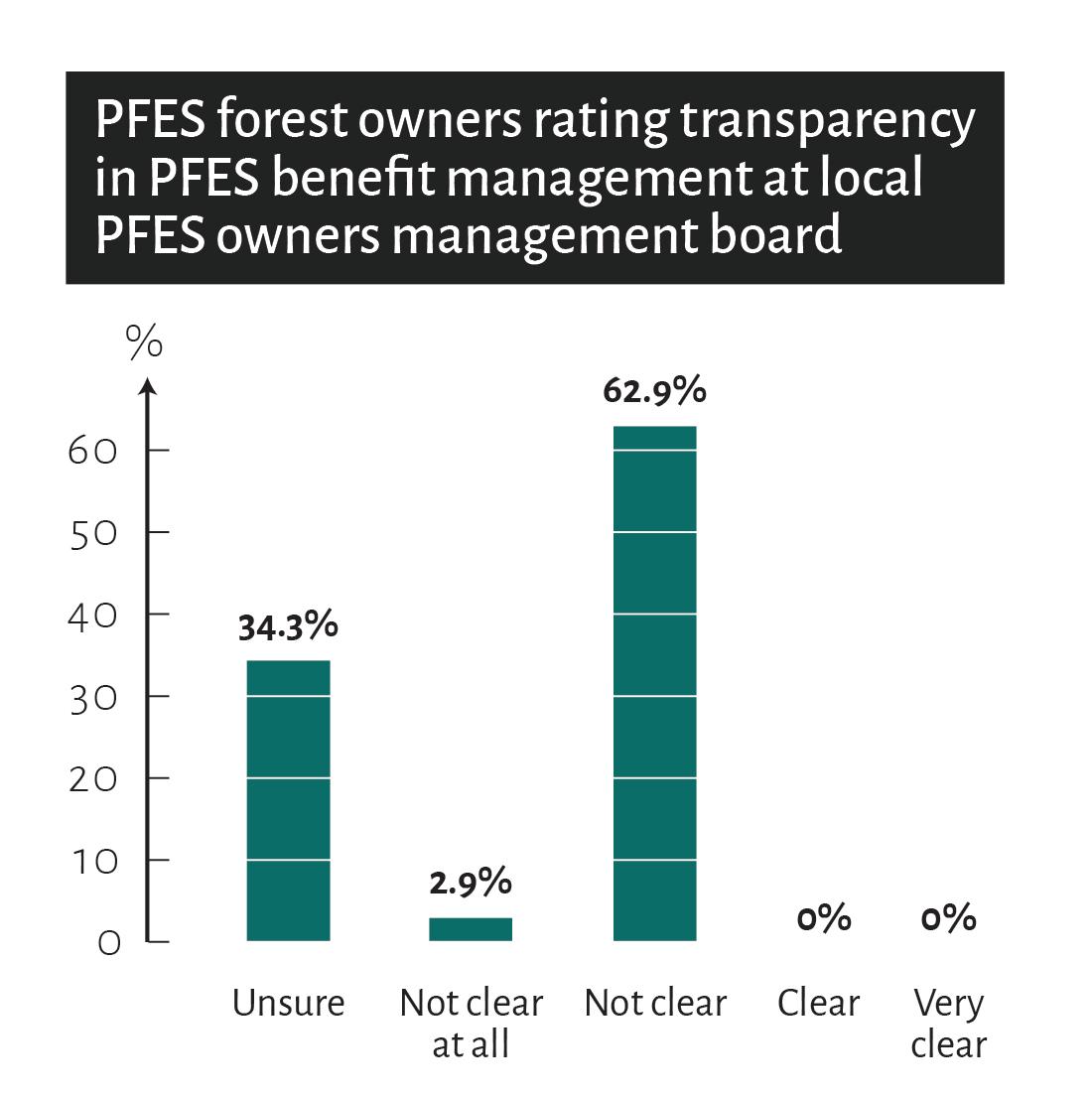

4.5 Discretion on the part of community forest owner management boards

PFES benefits are transferred via cash, bank accounts or e-payments to community forest owner management boards. These are small groups of people elected as representatives of the community forest group to manage the process of forest protection and receive/distribute PFES benefits for all members. As noted above, these boards play a decisive role in PFES benefit distribution, yet our research indicates a high level of discretion in how they operate, including how PFES benefit-sharing guidelines are interpreted.

First, spending on tools, for example, must demonstrate VAT (value-added or sales tax) receipts. But some boards buy tools in local markets without receipts. Second, spending on meetings and administration is largely determined at the discretion of the management boards. Third, the rates for daily fees for forest patrols are decided by the management boards.

In our survey, 62% of forest owners reported that the administration of community forest owner management boards was not clear to them. Given that potential corruption could occur not only at the step of PFES payments to these community forest management boards, but also in the boards’ own expenditures, the levels of discretion enjoyed by these boards could increase their vulnerability to corruption.

PFES forest owners rating transparency in PFES benefit management at local PFES owners management board

4.6 Limitations in monitoring the specifications in PFES contracts

Contracts signed between forest owners and PFES funds include specifications such as the total area of forest included in the schemes and the various responsibilities of different stakeholders. Low literacy and/or a lack of technical training appear to be leading to difficulties, not only in preparing the necessary documents but also in monitoring contract specifications in some communities. Defining the boundary between forest areas included in a PFES scheme, and those that are not, is technically challenging. Our research indicates that there has been collaboration between the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, local forest rangers and Forest Protection and Development Funds on applying remote sensing techniques to this task. At the same time, and as noted above, PFES forest owners and communities seem to have insufficient knowledge of how PFES forest areas and values are calculated. A particular area of confusion was as follows:

‘…we wonder why the [PFES] decree clearly stipulates 4 types of services that must be paid for… but now, more than 10 years ago, only 2 services have been performed. This can create psychological feelings of unfairness in payment for forest environmental services. Besides, we are also wondering about determining the area of watersheds applying PFES… and how much forest area is paid in each location.’842ab0936710

PFES, in theory, includes payments for four environmental services: (i) watershed protection, including soil protection, restriction of erosion and sedimentation of lakes, rivers and stream beds, and maintenance of water sources; (ii) protection of the natural landscape; (iii) carbon absorption; and (iv) provision of spawning grounds. However, we found that only the first two of these services were typically paid for. This is most likely because they were the first services to be piloted, while the third service is complicated to calculate, and the fourth typically involves only small sums. Regardless, forest owners did not understand why some services were not paid for. This lack of understanding combines with opacity regarding the methods for determining PFES payments. As a result, forest owners reported perceptions that monitoring PFES contract specifications was prohibitively hard.

5. Forest governance challenges beyond PFES

We observe that the wider forest governance context in which PFES is emerging in Vietnam is challenging and that e-payments are being rolled out amid differences of understanding between communities and elites, as well as illegal forest product supply chains. Some enterprises and forest owners have, for example, been allocated forestland by the government to implement afforestation projects or to restore forests from infrastructure projects. Some of these projects have been behind schedule for many years, while forest-dependent communities do not have enough forestland to carry out their livelihoods. Different views over access to forestland between communities and elites have emerged in many provinces, with one interviewee noting that this sometimes leads to forest encroachment on the part of PFES participants:

‘The current situation that many PFES forest owners lack production land while many large enterprises or forest owners who are allocated forestland do not implement or delay the implementation of projects, leads to non-used forestland. Meanwhile, people who comply with the regulations of the PFES scheme do not have land for production. So, they often encroach forestland for coffee, rubber or fruit trees as well as exploit forest products. Income from PFES participation is still small amount, thus we have to do so.’fdd3dd2a4235

This points to a paradoxical situation in which PFES forest owners lack land for their livelihoods, while others possessing land do not plant and protect forests, with this discrepancy driving at least some illegal forest encroachment. PFES e-payments are not designed to address these issues and should not be expected to discourage all forms of forest illegality, nor all forms of forest corruption. Rather, PFES e-payments are one part of a suite of interventions supporting a consistent, equitable and effective legal regime for forest protection and development.

6. Conclusion and policy suggestions

The introduction of PFES e-payments has been widely recognised as an interesting innovation in Vietnam, since the payments seem to enhance efficiency and traceability in benefit distribution. However, the theoretical additional benefit that these e-payments reduce opportunities for corruption is not easy to demonstrate empirically. The co-existence of e-payments with other payment forms, including cash; a lack of devices, technical services and financial literacy at some implementation sites (particularly remote, mountainous areas); limited transparency and participation in PFES payment calculations and processes; difficulties in monitoring PFES contract specifications and the administration of community forest management boards; and wider forest governance challenges all imply that e-payments are no panacea for tackling corruption linked to PFES benefit distribution in Vietnam. At the same time, our research shows that, given the right supporting conditions, it is feasible PFES e-payments could help reduce the potential for some corruption in benefit distribution and expenditure. With this in mind, we suggest the following:

- E-payments should ideally and ultimately become the sole mechanism for PFES benefit distribution across whole provinces. This would help generate systematic financial information and close the loopholes cash payments present.

- For this to be possible, ATM installation and support to electronic services (e.g., Viettel Pay) should be prioritised alongside long-term capacity building for officials, forest owners and forest owner management boards.

- Contracts for forest environmental services between the Forest Protection and Development Funds and forest owners should be subject to more thorough multistakeholder monitoring and scrutiny.

- A focus should be placed on equity in the determination of the K-index and PFES benefit calculation for each forest owner. This process should be adaptable but transparent to all PFES forest owners and should not simply follow a ‘one size fits all’ method.

- Participation and cooperation among PFES stakeholders (including forest owners, forest management boards, local forest rangers and officials) should be strengthened in determining forest boundaries and quality.

- All four forest environmental services (originally noted in Decree No.99/TTg) should be used in order to increase PFES benefits to forest owners.

- Measures aimed at resolving conflicts over accessing forests between PFES forest owners and elites are needed to improve and sustain the equity of PFES.

- Local governments should implement land acquisitions for old reforestation projects that are found to be behind schedule and reallocate forestland to relevant communities based on livelihood needs.

- Khanh 2020.

- Do and NaRanong 2019.

- Winrock 2021.

- All quotes in this Brief are English-language translations of results from our key informant interviews.

- Gómez-Baggethun et al. 2010; Wunder et al. 2008.

- Wunder 2007.

- Gómez-Baggethun et al. 2010.

- 2019.

- McElwee 2012; McElwee et al. 2019.

- McElwee 2004.

- McElwee 2004; To et al. 2017a; 2017b.

- Fritzen 2005; Rand and Tarp 2012.

- Rand and Tarp 2012.

- Fritzen 2005.

- Pham et al. 2013.

- Pham et al. 2013.

- 2016.

- Thompson 2017.

- Winrock 2021, p. 66.

- Viettel Pay is an electronic payment system, developed by the Viettel Group, which is widely used for PFES benefit distribution in Vietnam.

- Interview No. 14, Lam Dong province, 2021.

- Interview No. 5, Thua Thien Hue province 2021.

- Interviewee No. 24, Lam Dong province 2021.

- Interviews No. 25, Thua Thien Hue province, 2021.

- Interview No. 27 in Thua Thien Hue, 2021.

- Interview No. 7, Thua Thien Hue province, 2021.

- Interview No. 16, Thua Thien Hue province, 2021.

- Interview No. 8, Thua Thien Hue province, 2021.

- Interview No. 17, Lam Dong province, 2021.

- Interview No. 2, Lam Dong province, 2021.

- Interview No. 10, Lam Dong province, 2021.