Caveat

While a range wide of activities can directly or indirectly lead to the raising of public awareness of corruption, this paper focuses on campaigns that are deliberately carried out with the aim of dissuading corruption among the public in line with the understanding adopted by Rebegea (2023:7), among others.

Query

Please summarise the analytical debate on what sort of anti-corruption awareness raising campaigns work and provide any good practices of effective awareness campaigns.

Introduction

Article 13 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC 2003) calls upon states parties ‘to take measures….to raise public awareness regarding the existence, causes and gravity of and the threat posed by corruption’, thus recognising awareness raising as a key preventive measure against corruption. Beyond national governments, many anti-corruption actors including international organisations, civil society organisations and media carry out awareness raising campaigns to raise public consciousness around corruption, including through outreach conducted in schools, promoted through posters or billboards, or aired on television, radio and social media platforms (Sauve et al. 2023: 30).

Several attempts have been made by these actors to measure the ‘success’ of an awareness raising campaign in practice, including by testing the knowledge of audience members prior to and after being exposed to a campaign, monitoring the number of visits to social media websites and trying to prove a correlation with a change in corruption reporting rates (UNODC Secretariat 2013: 7). However, there are inherent empirical challenges to such efforts, for example, accurately identifying and tracking all audience members exposed to a campaign, as well as causally attributing any shift in their attitude or behaviour to the impact of the campaign’s content. Indeed, the effectiveness of awareness raising campaigns has been described as understudied in academic literature (Falisse and Leszczynska 2021: 97). Sauve et al. (2023: 32) argue that even though public awareness campaigns are widely used, there is insufficient evidence on their effectiveness in preventing corruption.

However, in recent years, an increasing number of scholars have conducted experimental studies to test the effects of awareness raising campaigns on treatment and control groups’ attitudes towards corruption and support for anti-corruption reform in the short term. Surprisingly, and perhaps even shockingly for campaigners, many of these studies have found that awareness raising campaigns often have little positive impact or even unintended negative consequences.

These findings raise a series of questions for anti-corruption campaigners: under what conditions are awareness campaigns (in)effective? Are there differences in effectiveness across different countries and contexts? Which kinds of messages or vehicles for messages are more effective than others?

To help address these questions, this Helpdesk paper proceeds as follows: firstly, it critically reviews recent research, mainly survey experiments, on the effects of anti-corruption awareness campaigns across various contexts. The paper highlights examples of innovative vehicles for spreading anti-corruption messages.

Effective anti-corruption messages

A growing body of research relying on experiments suggests that awareness campaigns may be ineffective or even exert a counterproductive influence on efforts to curb corruption. However, a closer examination reveals effects vary depending on the country, the scale of the campaign and, most importantly, the messages conveyed.

Guided by a typology set out by Peiffer and Cheeseman (2023: 9-10) and with reference to other academic literature, four different strands of anti-corruption messaging are considered in this section, including their assessed effectiveness and contextual variables in their deployment.

Message 1: Pervasiveness of corruption

Stahl (2022: 9) argues that awareness raising campaigns typically coalesce around messages framing corruption as a widespread phenomenon or highlighting its ‘evils’. Peiffer and Walton (2022:1) describe how initiators of these campaigns typically assume that such messages ‘will cause outrage in citizens, and second, that outrage will lead to citizens being more willing to act against corruption’.

They conducted a survey experiment in Port Moresby, the capital city of Papua New Guinea, highlighting the prevalence of corruption in the country through messages such as:

Corruption in Papua New Guinea is considered to be widespread throughout society, the private sector and across all public services and agencies. In a recent survey, 99% of respondents in PNG said that in PNG corruption is a very big or big problem. 90% said that corruption had gotten worse over the past decade. (2022:9)

However, they found exposure to this message did not increase survey subjects’ willingness to report corruption. This followed other studies with similar results. For example, Corbacho et al. (2016: 1088) conducted a survey experiment in Costa Rica demonstrating that participants were more inclined to consider bribing when they became aware of widespread corruption in society. Although this study did not explicitly investigate the effects of awareness campaigns, subsequent survey experiments have confirmed that messages highlighting the extent of corruption can diminish the willingness to curb corruption and enhance the propensity to engage in bribery (Peiffer 2017; Peiffer 2018; Cheeseman and Peiffer 2021; Cheeseman and Peiffer 2022). Similar results were yielded in a developed country setting; Köbis et al. (2015: 11) conducted laboratory experiments with students in the Netherlands. They found that the behaviour of recipients who received messages highlighting social norms about high levels of corruption did not differ in their propensity for corrupt behaviour compared to a control group of recipients who received no messages.

Overall, experimental studies indicate messages on the pervasiveness of corruption can backfire and have a rebound effect, particularly when citizens perceive corruption as an expected behaviour and become disincentivised to act against corruption or, unintentionally, incentivised to behave as corruptly as others (Persson et al. 2013: 456; Peiffer and Alvarez 2015: 53). Peiffer and Alvarez (2015: 353) termed this phenomenon ‘corruption fatigue’ where messaging which emphasises the pervasiveness of corruption make people less motivated to do anything to counter it.

Message 2: Immorality or negative consequences of corruption

Studies have analysed messages highlighting the immorality or negative consequences of corruption, finding they are typically ineffective in preventing corruption. Falisse and Leszczynska (2021), for example, conducted a lab-in-the-field experiment in Bujumbura, the economic capital of Burundi. Participants were exposed to messages emphasising that corruption is at odds with good governance and professional integrity. However, Falisse and Leszczynska (2021: 104) found that these messages had little effect on participants’ propensity to take bribes.

In addition, Peiffer and Walton (2022), as well as Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022), conducted survey experiments featuring messages focusing on the immorality or negative consequences of corruption, for example, emphasising that corruption is against religious teachings, it amounts to theft of tax money or that it is wealth lost to other countries. However, they found that these messages were either ineffective or counterproductive.

Wijaya and Pertiwi (2024) argue that messaging that reduces the problem of corruption to individual moral responsibility may be ineffective because it fails to reflect the complexity of everyday corruption and can place unrealistic expectations on the individual to address the problem of corruption.

Message 3: Progress against corruption

Compared to the outcomes associated with messages 1 and 2, experimental studies have demonstrated slightly more positive effects from messages highlighting progress in addressing corruption. Gans Morse (2018) conducted a survey experiment in Ukraine and tested whether negative (‘Corruption in Ukraine continues to increase’) and positively framed (‘Corruption in Ukraine is starting to decline’) messages affect willingness to pay bribes. The experiment found that positive messages may reduce the willingness to make bribe payments, in comparison to negative messages which sometimes cause unintended effects that increase the likelihood of corrupt behaviour.

Köbis et al. (2019) conducted a lab-in-the-field experiment in Manguzi, a small town in South Africa. They discovered that the use of posters with positive messaging (eg ‘Less and less people in KwaZulu-Natal pay bribes’) led more public officers to refuse to acceptbribes but did not significantly impact citizens’ propensity to offer them (Köbis et al. 2019: 611-612).

Notably, experimental studies caution against messages on progress which emphasise the successes of governments over those of citizens. Peiffer (2017; 2018) and Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) found that messages regarding successful government led corruption control can reduce citizens' willingness to act against corruption and increase their propensity to offer bribes. Peiffer and Alvarez (2015, 355) explain this by pointing out that citizens in highly corrupt countries are often sceptical of government led anti-corruption efforts. This suggests that awareness raising campaigns should carefully balance the portrayal of government led reforms, especially when public confidence in government effectiveness is low.

Message 4: Local relevance of (anti-)corruption

Another approach is awareness raising which emphasises the relevance of corruption as a local issue that affects the lives of citizens and their peers. As Jenkins (2022: 19) explains, such messaging aims to help citizens to see corruption not as an abstract issue but a matter that affects the interests of society as a whole (Jenkins 2022: 19).

Similar to Message 3, some experimental studies have revealed that such messaging can achieve intended effects on (anti-)corruption. For instance, Peiffer and Walton (2022) discovered that, in contrast to messages 1, 2 and 3, messages emphasising that corruption is a local issue significantly improved attitudes and willingness to report corruption. In this regard, Baez Camargo and Schönberg (2023: 13) note that more specific messaging which targets and is tailored to particular subsets of the public rather than the general public, can be more effective.

Agerberg (2021) carried out large-scale survey experiments in Mexico, distributing the following message to participants:

While corruption is a serious problem in Mexico, citizens strongly condemn corrupt practices. In a recent study by researchers at the University of Gothenburg that was specifically designed to elicit honest answers, a representative sample of Mexican respondents were asked about their attitudes towards corruption. Over 94 percent of respondents stated that accepting a bribe can never be justified (Agerberg 2021: 938)

He found such messages conveying strong public condemnation of corruption reduced citizens’ willingness to engage in bribery. Agerberg interprets the different outcome from Message 2 with reference to social norms. While Message 2 also constitutes a condemnation of corruption, it reflects a descriptive norm – perceptions about what others typically do – while the kind of message he used reflects an injunctive norm – perceptions of what is approved or disapproved by others (Agerberg 2021). He finds the latter to be more effective as it is more positively framed and reflects that even in contexts of endemic corruption, most people typically disapprove of corruption.

However, other studies have given different results. Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) found messages emphasising corruption as a local issue can increase the propensity of bribe payments. They (Cheeseman and Peiffer 2022b) also found that messages conveying strong public condemnation of corruption had no significant impact on the willingness to bribe, report corruption or on levels of tolerance towards corruption.

Table 1 expands on a table created by Peiffer and Cheeseman (2023) to summarise the four strands of messaging and studies identified by them and includes additional studies.

It should be noted that this is not an exhaustive list of studies, nor for that matter of kinds of messaging. For example, Jaunky et al. (2020) carried out an experimental study in Mauritius finding that messaging that seeks to simply increase public knowledge of the country’s Prevention of Corruption Act as effective in increasing the probability of reporting an act of corruption. Similarly, an experiment implemented by Blair et al. (2019) in Nigeria found that the combination of a film featuring actors reporting corruption followed by a mass text message, reducing the effort required to report, led to an increase in the willingness to report.

Table 1: Effectiveness of anti-corruption messages in select experiments

|

Type of message |

Measured outcome |

Effect |

Country |

Authors |

|

1. Pervasiveness of corruption |

||||

|

Increasing rate of bribery in country |

Propensity to bribe |

Unintended negative consequences |

Costa Rica |

Corbacho et al. (2016) |

|

Increasing corruption in country |

Propensity to bribe |

Unintended negative consequences |

Ukraine |

Gans Morse (2018) |

|

Grand corruption is endemic |

Support for government’s anti-corruption reform and confidence of citizen’s fight against corruption |

Unintended negative consequences |

Indonesia |

Peiffer (2017; 2018) |

|

Petty corruption is endemic |

Support for government’s anti-corruption reform and confidence of citizen’s fight against corruption |

Unintended negative consequences |

Indonesia |

Peiffer (2017; 2018) |

|

Corruption is endemic |

Propensity to bribe |

Unintended negative consequences |

Nigeria |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) |

|

Corruption is endemic |

Willingness to report corruption |

No effect or largely no effect |

Papua New Guinea |

Peiffer and Walton (2022) |

|

Corruption is endemic |

Propensity to bribe, willingness to report corruption, and intolerance to corruption |

No effect or largely no effect |

Albania |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2022b) |

|

Almost everybody behaves corruptly Nobody behaves corruptly |

Propensity to engage in corrupt behaviour |

No effect or largely no effect Intended positive effect |

Netherlands |

Köbis et al. (2015) |

|

2. Immorality and negative effects of corruption |

||||

|

Corruption |

Propensity to engage in corrupt behaviour |

Unintended negative consequences |

Uganda |

Cheromoi and Sebaggala (2018) |

|

Corruption is illegal |

Willingness to report corruption |

No effect or largely no effect |

Papua New Guinea |

Peiffer and Walton (2022) |

|

Corruption is against religious teachings |

Willingness to report corruption |

No effect or largely no effect |

Papua New Guinea |

Peiffer and Walton (2022) |

|

Corruption is against religious teachings |

Propensity to bribe |

Unintended negative consequences |

Nigeria |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) |

|

Corruption amounts to theft of tax money |

Propensity to bribe |

Unintended negative consequences |

Nigeria |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) |

|

Wealth is lost to other countries |

Propensity to bribe, willingness to corruption, and intolerance to corruption |

No effect or largely no effect |

Albania |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2022b) |

|

Corruption is at odds with good governance or professional integrity |

Bribe |

No effect or largely no effect |

Burundi |

Falisse and Leszczynska (2021) |

|

3. Progress against corruption |

||||

|

Government successes in anti-corruption |

Support for government’s anti-corruption reform and confidence of citizen’s fight against corruption |

Unintended negative consequences |

Indonesia |

Peiffer (2017; 2018) |

|

Government successes in anti-corruption |

Propensity to bribe |

Unintended negative consequences |

Nigeria |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) |

|

Reducing corruption in country |

Propensity to bribe |

Intended positive effect |

Ukraine |

Gans Morse (2018) |

|

Bribery declined recently in region |

Propensity to offer bribe Propensity to accept bribe |

No effect or largely no effect Intended positive effect |

South Africa |

Köbis et al. (2022) |

|

4. Local relevance of (anti-)corruption |

||||

|

Citizens can get involved in anti- corruption |

Support for government’s anti-corruption reform and confidence of citizens’ to act against corruption |

Unintended negative consequences |

Indonesia |

Peiffer (2017; 2018) |

|

Corruption is a ‘local’ issue |

Willingness to report corruption |

Intended positive effect |

Papua New Guinea |

Peiffer and Walton (2022) |

|

Corruption is a ‘local’ issue |

Propensity to bribe |

Unintended negative consequences |

Nigeria |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) |

|

Citizens strongly condemn corruption |

Propensity to bribe |

Intended positive effect |

Mexico |

Agerberg (2021) |

|

Citizens strongly condemn corruption |

Propensity to bribe, report willingness to corruption, and intolerance to corruption |

Unintended negative consequences |

Albania |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2022b) |

Best practices

This section complements the previous section by describing three best practices of awareness raising campaigns. While their effectiveness has, largely speaking, not been subjected to the same rigorous testing as the experimental studies in the previous sections, they appear to have been effective in achieving certain outcomes. Notably, these examples show positive effects of messaging built around messages 3 and 4, as well as using engaging formats and tailoring content to specific cultural contexts.

Integrity Icon campaign

Integrity Icon, formerly known as Integrity Idol, is a global citizens’ campaign, often run annually or biannually to ‘name and fame’ honest public servants (Integrity Idol 2018). Originating in Nepal in 2014, the competition has since expanded to multiple countries, including Afghanistan, Indonesia, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Africa and Sri Lanka. According to its official website, it is a process-oriented campaign, rather than an outcome-oriented one, aiming ‘to create meaningful conversations about what it means to be a public servant and shines a light on the role of ordinary people in strengthening institutions’ (Integrity Icon 2024a).

The selection process begins with citizens nominating public officials. These nominees then submit films to demonstrate their innovative methods or experience of promoting integrity and/or countering corruption in challenging environments. Finally, citizens vote for their preferred candidates via SMS or the website to decide the winner(s), Integrity Icon(s) (Pattisson 2014; Integrity Icon 2024b).

Public officials nominated as Integrity Icons are expected to have unwavering commitment to high standards of public service, often at the local level, which extends beyond their professional responsibilities (Integrity Icon 2022). For example, Tariro Zitsenga, a nurse at Parirenyatwa Hospital, the largest medical centre in Zimbabwe, was named as an Integrity Icon in 2022. She was selected not only because she had never asked for bribes from patients but also because she has trained colleagues to provide patient care in their homes so that they can earn extra income and ideally discourage them from asking bribes for patients (Integrity Icon 2023). Also, as a long-term effect of the campaign, it is worth noting that public officials, nominated as Integrity Icons for reasons other than their anti-corruption efforts, have started to promote anti-corruption by leveraging the community among Integrity Icons. Nassou Keita in Mali represents a notable example. Originally nominated for her dedication to active youth education, including outreach to rural girls, Keita has integrated lessons on integrity into her school’s curriculum since her nomination in 2017 (Russell 2018).

Many scholars in the field of anti-corruption have evaluated the awareness raising effects of the Integrity Icon campaign positively in the literature. For instance, Hough (2017: 156) notes that the Integrity Icon campaigns innovatively ‘plant the seed of anti-corruption in the minds of those watching’ over the long term and ‘prompt discussion about how to make those in the Nepalese public service behave more like Integrity Idol winners’.

Similarly, Kukutschka (2018: 7) highlights the success based on the campaign's enduring presence in various countries and the growing participation of citizens in the form of nominations and votes. Regarding the reasons for these successes, Kukutschka points out that (i) the campaign can engage a broader range of citizens through television and (ii) participation is ‘safe and anonymous’.

Bentley and Mullard (2019) analysed a youth fellowship programme that was part of the Integrity Icon programme in Nepal. They explain that in Nepal, young people generally expect to encounter corruption in public services and have low levels of trust in civil servants. The programmes pair young people with civil servants who have been nominated as Integrity Icons, giving them the chance to shadow them during their work and free time. Bentley and Mullard found that this approach focusing on direct interaction with “integrity trendsetters” was largely successful in changing the participating young peoples’ pessimistic opinions about corruption and increased their levels of social trust in civil servants. Furthermore, it was found to increase their interest in working in public administration themselves and to work with integrity in such roles.

The continuous operation of Integrity Icon across various countries as well as active and growing citizen participation in the campaign demonstrates not only its success but also the importance of emphasising positive cases or trends in efforts to counter corruption. Indeed, Blair Glencorse, the founder and Executive Director of Accountability Lab, emphasises that Integrity Icon ‘reframes the issue in a positive way’ and ‘shifts the debate from people who embody problems to those who embody solutions’ (Quinn 2017). The positive tone of the naming and faming approach brings it more in line with messages 3 and 4 from the previous section compared to the more pessimistic tone of messages 1 and 2.

Glencorse (2020) has noted other positive, long-term effects of the Integrity Icon campaigns. For example, a former winner in Mali used the publicity he received to develop his career, subsequently becoming minister of justice where he reportedly enhanced the anti-corruption portfolio.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the effects of such campaigns may be limited in certain contexts. Buntaine et al. (2023) carried out field experiments in Uganda on awards systems similar to the Integrity Icon campaign and found that the knock-on effect was limited, namely that informing other leaders and residents about the award winners also did not change behaviour or attitudes related to corruption, but rather their resignation towards the sense of endemic corruption prevailed.

Video edutainment

Examples from Greece and Ukraine demonstrate that video campaigns using an ‘edutainment’ approach can effectively capture the attention of specific audiences. Edutainment is education ‘that relies heavily on visual material, on narrative or game-like formats, and on more informal, less didactic styles of address’. Scholars in education have discussed the possibilities of edutainment to keep the audience’s attention ‘by engaging their emotions’ since the 2000s (Okan 2003: 255). Kassa et al. (2017) argue edutainment has strong potential for anti-corruption awareness raising.

From 2016 to 2018, the Greek government, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Commission initiated an anti-corruption project called the Greece-OECD project. This project aimed to assist Greece with the government’s national anti-corruption action plan revised in 2015 (OECD n.d.).

A notable component of this initiative was a YouTube anti-corruption awareness raising campaign. Distinctively, this campaign collaborated with a diverse array of stakeholders, including government, international organisations and popular social media influencers. For instance, as part of the Greece-OECD project, Konilo, a well-known Greek YouTuber, created videos about what people like and dislike about Greece. In these videos, he interspersed discussions with young citizens of everyday corruption with lighter topics, such as Greek cuisine or weather (Konilo 2017; Gyimesi 2019)

Youth engagement with the videos was positive. Reaching the campaign's target audience, with 78% of viewers being young people, these videos accumulated about 900,000 views. Additionally, one video created by Konilo achieved the number one trending position on Greek YouTube at one point, with a significant amount of positive feedback (OECD n.d.).

An experimental study carried out by Denisova-Schmidt et al. (2019) in Ukraine lends empirical credence to the effectiveness of such campaigns. They showed three different videos on corruption and its consequences to over 3,000 survey participants. The results indicated that one video depicting ‘a thrilling story about a victim of corruption related to common bribery in an accessible way’ was more effective in raising awareness than the other two which ‘followed the style of TV news or documentaries on corruption’. Denisova-Schmidt et al. concluded that it was important to package anti-corruption messages in an entertaining way.

Cartoon campaigns

In some countries, certain kinds of anti-corruption messages and certain forms of vehicles for such messages may be more effective than others.

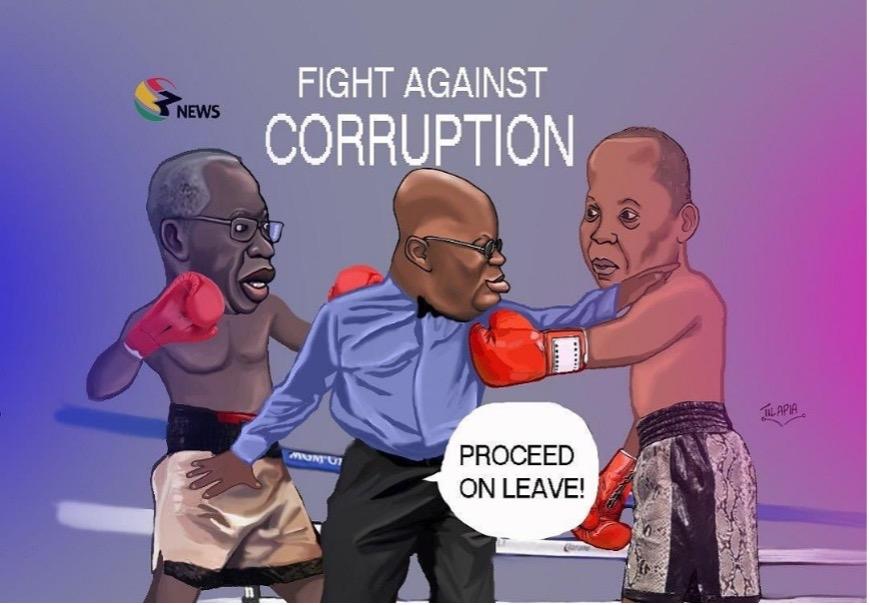

Ofori and Sena Dogbatse (2023) describe anti-corruption awareness messaging undertaken by popular cartoonist Tilapia Da Cartoonist on his Facebook page. He is a renowned cartoonist and visual communicator on 3News.com, a major online platform in Ghana, and often illustrates cartoons on corruption in Ghana.

For example, the cartoon shown in Figure 1 depicts a boxing match between the former Ghanaian senior minister Yaw Osafo Marfo (left) and former auditor-general Daniel Domelevo (right). The cartoon captures the moment the match is abruptly halted by a referee who orders Domelevo to ‘proceed on leave’.

Figure 1: Cartoon: Fight against corruption - proceed on leave

TV3 Ghana 2020; Ofori and Sena Dogbatse; 2023: 92.

Domelevo was appointed auditor-general at the end of 2016 after serving as a senior financial management specialist at the World Bank. During his tenure, for example, he succeeded in recovering US$11.7 million in stolen assets in 2018 (African Confidential 2021). However, in July 2020, after Domelevo began investigating Osafo Marfo for corrupt dealings, President Akufo-Addo controversially ordered him to take his accumulated 128 leave days (Ghana News Agency 2023; Ofori and Sena Dogbatse 2023: 93). As Ofori and Sena Dogbatse (2023: 94) explain, it illustrates ‘the lack of fairness and commitment’ in Ghana’s measures to curb corruption.

While cartoons by Tilapia Da Cartoonist predominantly feature a negative orientation in line with messages 1 or 2 – either highlighting corruption cases or illustrating the challenges of countering corruption – they seem to attract significant public attention, often receiving more than 1,000 reactions.

This case suggests that contextualised awareness raising campaigns, based on real-life cases rather than abstract messaging and presented in an engaging manner such as cartoons, may effectively and attractively convey campaigner’s messages about (anti-)corruption in the country. Anti-corruption campaigners’ deep understanding of the contexts, such as the culture of corruption and trends of corruption control in the area, influence target audience effectively (Stahl 2022: 15-16).

The popularity of the cartoons also overlaps with another conclusion reached by Asomah (2020), namely that, in the Ghanian context, private media channels are critical players in raising awareness of and educating the public about corruption. Tilapia Da Cartoonist’s work with 3News.com presumably helps him with the dissemination of his messages.

Cartoons have been recognised as an effective tool for raising awareness of corruption in other contexts; for example, Transparency International Bangladesh (2023) showed that cartoons are effective vehicles for anti-corruption content because cartoons are a popular medium in the country, including among young people.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of anti-corruption campaigns varies significantly depending on the strategies employed. While experimental studies have shown that simply highlighting the pervasiveness and illegality of corruption does not effectively change behavior or attitudes toward anti-corruption efforts, other approaches that emphasize positive trends of anti-corruption and the relevance of corruption in everyday life, as well as citizens' strong condemnation of it, appear to be more promising.

Case studies have provided more nuanced lessons about anti-corruption awareness campaigns. The case of Integrity Icon, for instance, has underscored the importance of focusing on positive examples rather than merely condemning wrongdoing. The effectiveness of anti-corruption messages can also be enhanced by tailoring content to specific cultural contexts and using engaging formats. Examples from Greece and Ukraine demonstrate that video campaigns using an edutainment approach can effectively capture the attention of specific audiences. In Ghana, 'Tilapia Da Cartoonist' uses memes to communicate anti-corruption messages, illustrating the power of context-sensitive content shared through locally popular memes.

Overall, the mixed results of different anti-corruption awareness raising efforts highlight the need for deliberate and nuanced messaging that is responsive to the profile of the target audience.