Query

Please explore corruption risks, as well as corruption's negative effect on healthcare, the environment and the readymade garments industry. Where possible, identify entry points and innovative approaches to prevent, mitigate and detect corruption.

Background

Bangladesh has grown economically from ‘the test case for development’ to middle-income status in 2021. The country is on track to graduate from a Least Developed Country (LDC) to a developing nation by 202662e0fa98eea2 (Barkat-e-Khuda 2021; Byron and Mirdha 2021; World Bank 2021).

While the terms ‘middle-income economy’ and ‘developing country’ have been used almost interchangeably in the Bangladeshi national context, they are not one and the same, and the distinction between them is essential to the policies associated with each (Bhattacharya and Khan 2018, 1).

A 2018 report from the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) argues that Bangladesh should have been considered a middle-income economy since 2015, when it reached the lower middle-income country category (Bhattacharya and Khan 2018, 1, 4). The report notes , however, that metrics based solely on income are insufficient for capturing a country's strengths and vulnerabilities (Bhattacharya and Khan 2018, 1, 2). For example, a country with higher income levels may still be an LDC given underlying socio-political weaknesses (Bhattacharya and Khan 2018, 2).

Countries with LDC status receive various export benefits, such as complete or almost complete duty-free, quota-free (DFQF) access to developed markets and more favourable rules of origine8e25216af0d (UN 2021). Bangladesh’s export sector achieved high growth rates in part due to multilateral, regional and bilateral trade preferences from its LDC status, according to a 2014 study from the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) (Rahman 2014, 28).

The ready-made garment industry (RMG) contributes almost four-fifths of the country’s total global export earnings and will be impacted when Bangladesh loses its current export advantages (Rahman 2019). While the trade benefits will continue until 2026, Mustafizur Rahman, a distinguished fellow at CPD, has said the RMG sector should undertake various initiatives, including “technological upgrading, social compliance, and labour standards and rights compliance, to address the post LDC-graduation challenges” (Byron and Mirdha 2021; Rahman 2019a).

Nevertheless, the LDC transition is taking place because the country has made significant socio-economic progress, as indicated by the reduction in the poverty rate (from around 83 per cent in 1975 to 20.5 per cent in 2019) (World Bank 2021; Byron and Mirdha 2021). In fact, Bangladesh has been one of the fastest-growing economies of the last decade. However, it still faces significant development challenges. They include (Barkat-e-Khuda 2021):

- infrastructure shortfalls

- stagnation in the investment-to-GDP ratio, which adversely impacts the private sector

- income inequality

- poor health care

- poor education

- insufficient coordination among law enforcement and implementing agencies

- weak monitoring and supervision in governance activities

- poor accountability and transparency

Endemic corruption remains an overarching challenge, and little headway has been made in curbing the problem, particularly because anti-corruption efforts are often highly politicised, as indicated in recent reports from the Bertelsmann Stiftung (2021) and Freedom House (2021a).

The current Awami League-led government headed by Sheikh Hasina has tightened its grip on power by cracking down on free speech, harassing opposition parties, arresting critics and censoring the media (Freedom House 2021a; HRW 2021).

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected Bangladesh (World Bank 2021). In addition to the impact on public health, GDP growth has slowed down, poverty rates have gone up to about 30 per cent, and major economic recessions have caused a rise in hunger (Barkat-e-Khuda 2021; Rahman et al. 2020; World Bank 2021).

The World Bank (2021) states that diminished female labour force participation, educational setbacks and increased financial sector vulnerabilities stemming from the pandemic will have long-term economic implications for the country. While these implications may complicate Bangladesh’s goal of reaching upper-middle-income status, the World Bank (2021) adds that the correct policies and appropriate action can speed the country’s recovery from the economic downturn to resume its progress.

However, poor management, corruption, inadequate public awareness, limited compliance with social distancing rules and low levels of vaccination stemming from public mistrust have significantly hampered the pandemic response in the country (Rahman et al. 2021, 191, 195).

Extent and forms of corruption

Bangladesh ranks 146 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) with a score of 26 out of 100 (Transparency International 2021).

The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (2020) assign the following scores (in percentile rank) to the country:6188318fa9fe

|

Indicator |

2015 |

2017 |

2019 |

|

Control of corruption |

22.1 |

19.2 |

16.3 |

|

Government effectiveness |

24.0 |

22.1 |

23.6 |

|

Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism |

10.0 |

10.5 |

15.2 |

|

Regulatory quality |

18.3 |

20.7 |

15.4 |

|

The rule of law |

26.0 |

28.4 |

27.9 |

|

Voice and accountability |

30.5 |

30.0 |

27.1 |

Many scores, including control of corruption and voice and accountability, worsened between 2015 and 2019.

The 2019 TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix places Bangladesh in the ‘high’ risk category, ranking it 166 out of 194 countries with a score of 66 – the highest in South Asia (TRACE International 2019; The Daily Star 2021).

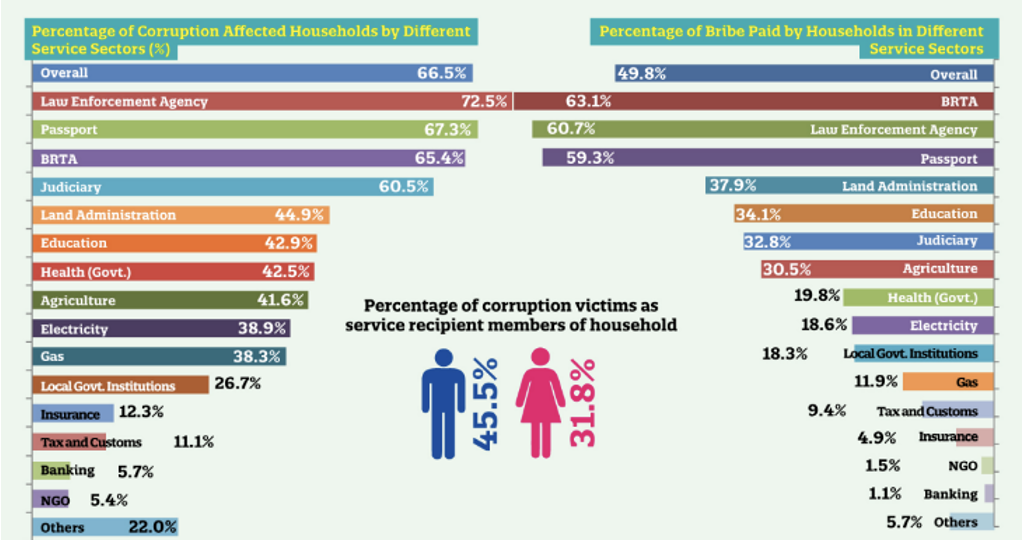

A national household survey conducted by Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) in 2017 on corruption in the service sector had several noteworthy results (TIB 2018a, 13, 15):

- Survey respondents reported the highest levels of corruption in law enforcement agencies (72.5 per cent), passport offices (67.3 per cent), road transportation agencies (65.4 per cent) and the judiciary (60.4 per cent).

- The most common form of corruption was bribery, which 49.8 per cent of respondents encountered while using public services.

- 89 per cent of respondents who admitted to paying bribes believed the service they were seeking would not have been rendered otherwise.

Figure 1: Sectors affected by corruption according to the National Household Survey 2017 by TIB

Source: (TIB 2018a).

Petty corruption, especially bribery, is particularly widespread across the socio-economic spectrum in Bangladesh. The US Department of State (2020, 25) notes that public organisations and government officials remain susceptible to corruption. For example, there have been several reports during the pandemic of local authorities embezzling from government food assistance and relief programmes (US Department of State 2020, 25).

Kabir et al. (2020, 20) note that ‘corruption is so pervasive at both micro and macro levels that it threatens to become a way of life’, adding that political, grand and petty forms of corruption are commonplace in Bangladesh. For further details on the forms of corruption in the country, refer to this previous Helpdesk Answer from 2019 Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in Bangladesh.

Focus Areas

Ready-made garments (RMG)

Employing close to 4.5 million people, the ready-made garment (RMG) sector is a key industry in Bangladesh. RMG has significantly contributed to overall economic growth in recent years (Barkat-e-Khuda 2021).

The RMG sector has caused significant structural changes to Bangladesh's economy, such as (Barkat-e-Khuda 2021):

- shifting economic dependence from foreign aid to export earnings.

- comprehensive development of export structures,1519d64c54e2 and a corresponding shift from essential goods to manufactured goods

- a predominantly female workforce, which, has empowered women financially in the country.

In 2019, 11.17 per cent of GDP and 83.51 per cent of all exports came from the RMG sector (TIB 2019). For July 2020 to March 2021, revenues from RMG amounted to US$29.8 billion. While still a significant increase over the US$6.5 billion in revenue in 2005, export income has fallen from US$35 billion before the COVID-19 pandemic (Barkat-e-Khuda 2021). According to the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), textile exports dropped by nearly 17 per cent in 2020 (Ahmed 2021). Almost 360,000 people have lost their jobs, with thousands more accepting lower wages to survive (Rahman and Yadlapalli 2021).

The RMG sector will be heavily affected by the graduation of Bangladesh from LDC to developing country status in 2026. The Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) estimates that Bangladesh's exports will face an extra tariff of around 6.7 per cent from preference erosion and more stringent rules of origin (Rahman 2019a). Rahman (2019a) notes that such a scenario will adversely impact the ‘competitiveness of Bangladesh's apparels exports to the global market’. Offsetting the situation in the long run would require Bangladesh to enter into free trade agreements (FTAs) with its key trading partners and improving its ‘ability to ensure compliance and enforce standards (labour, social, technical, intellectual property rights, environmental)’ (Rahman 2019a).

Despite contributing heavily to Bangladesh’s overall development and growth, the RMG sector is not free from corruption challenges. In 2013, the country suffered its worst industrial disaster when Rana Plaza, a building housing five garment factories, collapsed, killing 1,100 people and injuring another 2,500 (Ogrodnik 2013).

Corruption and graft were the root causes of the disaster. Construction rules were flouted and corners were cut in procuring building materials, while officials took bribes to look the other way (OCCRP 2014; Transparency International 2014). The building owner, Rana, even forced employees to continue working despite visible cracks on the walls of the building (OCCRP 2014). The owner was subsequently jailed in 2017 on charges of accumulating property and money through corrupt practices (Al Jazeera 2017). Several international players immediately mobilised to create an Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (a legally binding pact meant to guarantee safe workspaces for garment workers) as well as a Worker Safety Initiative (Shiina 2015).

While the situation has improved, a lot still needs to be done to ensure compliance with safety norms and welfare for workers, especially in smaller factories where work is often sub-contracted (TIB 2019). Legal limitations, lack of political will and the influence of factory owners hamper workers' collective bargaining power (TIB 2019, 9). Much progress is needed in the areas of compensation for accidents and loss of jobs, social safety for injuries, maternity benefits (given that the workforce in the sector is primarily female), accountability of corrupt actors, and due legal processes for the prosecution of offenders (TIB 2019). Rahman and Yadlapalli (2021) contend that there remains a ‘fundamental problem in global supply chains [with a] disconnect between profits, accountability and responsibility’. For example, one report suggests that compliance programmes will do little to change on-the-ground realities, as they do not address the root causes of poor working conditions (a business model based on manufacturing huge quantities of goods with tremendously quick turnaround as cheaply as possible). Moreover, competition with other countries directly feeds into the RMG sector’s ‘weakened regulation, poor enforcement, insufficient inspection, allegations of corruption, inadequate audits, disempowered unions and lack of adherence to international norms’ (IHRB & Chowdhury Centre for Bangladesh studies at UC Berkeley 2021).

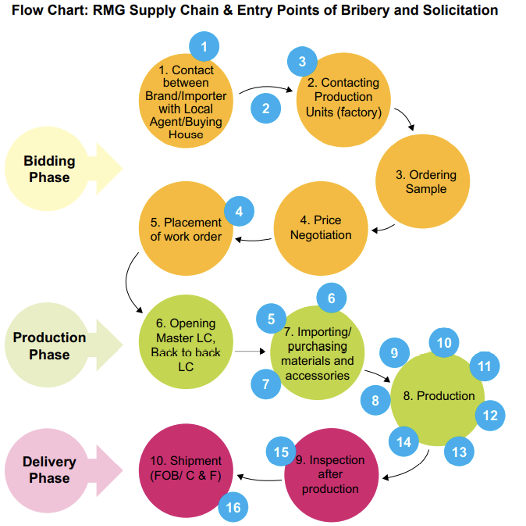

In 2017, Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) mapped out potential corruption risks and their entry points in the value chain of RMGs. The following infographic highlights the RMG supply chain.

Power imbalances in RMG

The Clean Clothes Campaign, a global network dedicated to improving working conditions in the garment industry, notes that major brands dictate pricing and payment terms in apparel supply chains. Most brands are well-resourced with access to global capital and in a situation to pit suppliers against one another during negotiations. In contrast, suppliers are focused on becoming more efficient than their competitors. Brands often choose to base their supply chains in countries with low wages and weak social protections (such as Bangladesh).

In essence, brands' financial power allows them to dictate how profits are made and distributed along their supply, leading to an ‘ever-smaller share available for suppliers to pay their workers decent wages, ensure safe and healthy working conditions, or provide workers with legally mandated benefits upon termination’. Thus, global garment supply chains are defined by ‘an acute power imbalance between brands at the top and workers employed in factories’ (IHRB & Chowdhury Centre for Bangladesh studies at UC Berkeley 2021).

Figure 2: Value chain for the ready-made garment sector

Source: See TIB 2017, 14.

Each stage of the RMG value chain presents its own unique corruption challenges (TIB 2017, 17 -30):

Bidding phase (TIB 2017, 17-19):

- bribing compliance auditors to mislead buyers that a manufacturer is meeting safety and quality standards

- manufacturers (large and small companies) using kickbacks, bribery, bid-rigging and collusion to secure a work order

- using fake documents to secure contracts

Production phase (TIB 2017, 20-27):

- tampering with factory records

- paying kickbacks to merchandisers

- merchandisers coercing production units (PU) to procure materials from suppliers that reward merchandisers with a share of the profits

- importing more materials than required and selling the additional materials on the open market

- using contracts with a compliant supplier to obtain Letters of Credit (LC) from banks, but then purchasing materials at a lower price from other suppliers at the time of encashment

- violating minimum wage, work hours and labour rights

- illegal sub-contracting

Delivery phase (TIB 2017, 28-30):

- bribing auditors and quality inspectors

- manipulating compliance reports

- threatening manufacturers with order cancellation at the time of delivery or port inspection to obtain additional discounts

After the delivery phase, new corruption risks arise during the export phase. An ongoing study by Khan, Ahmed and Ahamed reveals that smuggling from bonded warehousingb0396716f062 severely affects the growth of domestic industries and results in a significant loss of revenue for the Bangladeshi government (BIGD 2021).

Transparency International Bangladesh issued recommendations in 2017 for different actors to mitigate corruption risks in the RMG sector, including (TIB 2017, 32-38):

Companies (factories, buyers, auditing firms):

- Establishing codesestablish codes of conduct and standard operating procedures

- publish and enforce a zero tolerance anti-bribery policy

- set up clear-cut company directives such as a whistleblowing policy and due sanctions for non-compliance (for example, termination of employment and cancellation of work orders)

- make clear the consequences of non-compliance, including reputational risks, for both the business and employees

- train relevant personnel on the repercussions of bribery (including regulations involved), and anti-competitive deals. Also teach appropriate responses to such actors when they are faced with bribe demands (for example, avoiding payment, use of reporting channels, etc.)

- introduce anti-corruption clauses and auditing obligations into contracts with business partners, such as suppliers, sub-contractors, agents and consultants

- have a gift policy

- conduct regular background checks for vendors and suppliers

- carry out internal audits for end-to-end business processes and establishment of feedback mechanisms

Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA):

- train members on appropriate anti-corruption, worker-safety and labour laws to ensure adequate implementation

- establish a list of certified third-party auditing firms

- develop a collective-action initiative with buyers to maintain a list of garment factories that meet the compliance standards set by different buying coalitions

Government:

- set up unique identification numbers for factories to hinder duplication or editing of any information

- establish a monitoring cell to ensure implementation of safety rules and minimum wage

- launch a grievance centre for arbitration about labour rights and business integrity

Civil society:

- institute an anonymous whistleblowing hotline (to report unethical, dishonest and unfair dealings)

- monitor the implementation of the above-mentioned recommendations

- prepare reports and raise awareness

When it comes to combating corruption, including in the RMG sector, Khandd1352ceb864 (2013, 30) cautions that ‘good governance, as it is understood in the international policy discourse, [is] an impossible challenge’ and suggests a focus on ‘developmental’’ governance capabilities could yield better results (Khan 2013; SOAS 2021). Khan adds that ‘corruption can increase if you try to make people follow rules who have no capacity yet’, stating that the primary focus should be on building capacity so that laws have a suitable foundation in society for implementation (Nazrul 2021).

Berg et al. (2021) note that the country’s preferential access to European and other markets is up for negotiation as it graduates from its LDC status. Discussions between relevant stakeholders, such as the BGMEA, policymakers and economists, are currently underway regarding the challenges the sector may face once Bangladesh transitions (Biswas 2021). Nevertheless, a trained work force, low overhead costs, a business-friendly government and recent efforts to move the sector towards sustainable production practices are reportedly helping Bangladesh remain a popular destination for foreign RMG buyers (Berg et al. 2021; Biswas 2021).

Health

Globally, the health sector tends to be especially vulnerable to corruption because of many resources, information asymmetry, the considerable actors involved, 'system complexity and fragmentation, and the globalised supply chain for drugs and medical devices' (Hussman 2020).

Corruption was commonplace in the health sector even before the COVID-19 pandemic, ranging from bribery at the service delivery level to undue influence at higher levels of procurement and decision making (Bay 2020). Iftekharuzzaman, the executive director of Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), has said that the ‘pandemic has been converted into a festival of corruption in the health sector in Bangladesh’ (2020).

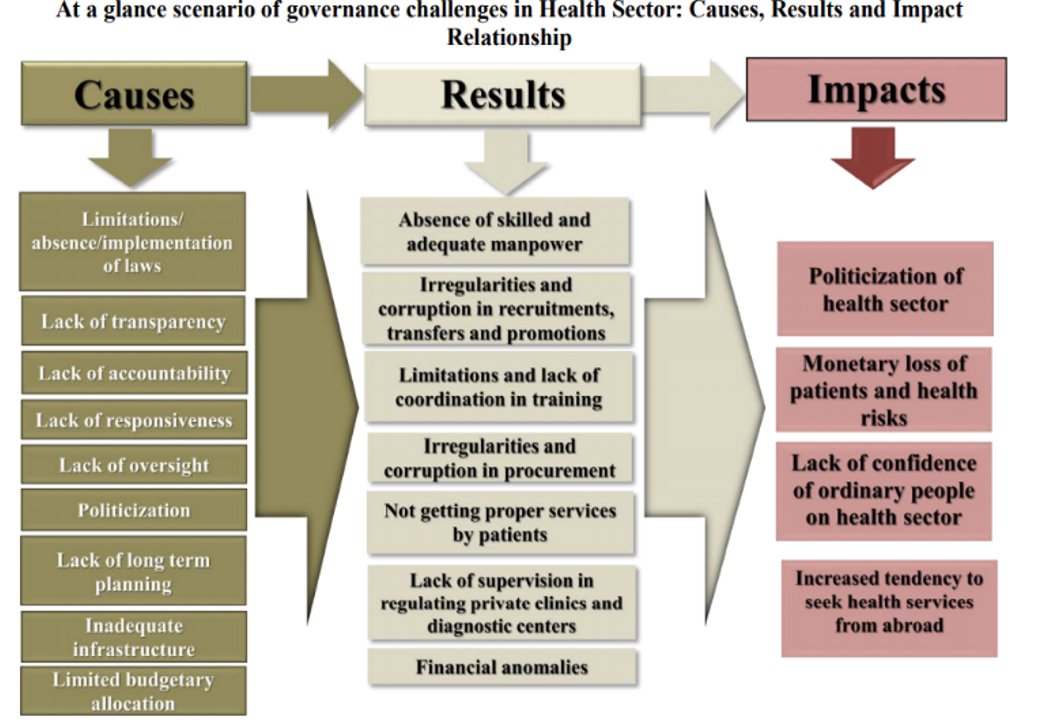

Pre-pandemic challenges in the Bangladeshi health sector included (Ahmed et al. 2015, 154; Joarder et al., 1-6):

- poor governance and complexities arising from mixed health care systems (for example, public, for-profit private, not-for-profit private [mainly NGOs] and international development organisations)

- inadequate resource allocation, lack of operational protocols and weak infrastructure

- uneven health service coverage and health care financing through out-of-pocket payments. Health expenditures have forced up to 5.7 million Bangladeshis into poverty.

- inequitable access to health services due to political, social, economic and demographic barriers

- low levels of trust in health insurance and health care agencies

Figure 3: an overview of governance challenges in Bangladesh's health sector

Source: TIB-2014.

Since the onset of COVID-19, Julkarnayeen et al. (2020, 12) have noted several new challenges affecting the health system in the country:

- lack of good governance in the pandemic response, including poor planning, coordination and communication between government ministries

- mismanagement resulting in infrequent testing and community spread

- bureaucratic officials overruling specialists, resulting in political decisions being made over those that would be best for combatting the pandemic

- misinformation, low trust in government and lack of awareness, all of which hamper compliance with lockdowns .

- corruption in the procurement and supply of health products

- poor coordination and theft in relief distribution

- insufficient financial support for the extremely poor

- an overall tendency to cover up irregularities, corruption and mismanagement through restrictions on disclosure of information. A lack of accountability and poor whistleblower protection contribute towards corruption in the sector.

Currently, there are high rates of vaccination refusal, especially in the rural population, due to low levels of trust in the health sector and government (Abedin et al. 2021).

Corruption exacerbates the COVID-19 crisis

According to Muzaherul Huq, a former regional advisor of the World Health Organisation, ‘COVID-19 exposed [Bangladesh’s] muddled, weak and corrupt health system’.Before the pandemic, the sector was already severely affected by corruption risks in the form of bribery, procurement fraud and lack of oversight (Maswood 2020).

Rahman et al. (2021) note that the Bangladeshi public health care system is overburdened. The government spends only five per cent of the country's GDP on health. Private health care has grown substantially in the past few decades, but the sector is rife with allegations of corruption and inefficiency, including ‘higher treatment cost, wrong diagnosis of diseases, commission-based services, running of healthcare services without registration and overall deficiency in the expected service quality’ (TIB 2018b).

Corruption risks affecting the health sector include:

- Bribery: 19.8 per cent of households paid bribes to access public health care services, according to the 2017 NHS (TIB 2018a). Citizens have also reported demands for bribes for COVID-19 testing and the issuance of fake reports for travel during the pandemic (Iftekharuzzaman 2020; NewAge 2021).

- Procurement fraud: the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) recently prosecuted five people in three different cases on charges of embezzling over Tk4 crore (US$4,70,00) in procuring hospital equipment (Dhaka Tribune 2021a).

- Political lobbying: in the past, political lobbying has led to the establishment of hospitals and clinics in inadequate places such as residential apartments and rented buildings (Akter and Julkarnayeen 2018, 6). Moreover, intense political lobbying has also prevented the closure of inadequate health care facilities (The Daily Star 2018).

- Political interference: recruitment, retention and management of medical staff, especially doctors, is difficult in the public health care system due to bureaucratic and political interference. Local government health officials have said political leaders issue regular directives on where to station doctors and protect doctors who are absent or not following protocol (Joarder et al. 2019).

Reported cases of corruption in the health sector during the pandemic include (Al-Zaman 2020, 1358; Julkarnayeen et al. 2021, 11):

- Medical equipment procurement fraud: Tajuddin Medical College’s proposed expenditure was US$20.7 million, which was 10 times higher than the actual expenditure. Also, the products were of poor quality.

- Fake report scams: Regent Hospital reported 10,500 COVID-19 tests, but 6,300 were fake reports. Another hospital known as JKG Health Care, which is approved by Directorate General of Health Services, set up 44 booths for COVID-19 testing. Workers at these booths sold US$0.94 million worth of fake reports.

- Irregularities in relief distribution: By June 2020, 218 incidents of corruption regarding relief distribution were reported in the media involving elected representatives (30 per cent), local political leaders (24 per cent), dealers (17 per cent) and businesspeople (14 per cent).

Stress on health systems has impaired treatment of non-Covid diseases such as heart disease, diabetes and mental health conditions (Barkat-e-Khuda 2021). Government ministries have denied reports from civil society actors such as Transparency International Bangladesh on the lack of testing facilities and poor health governance (The Business Standard 2021). There has also been a strict crackdown on those publicly raising concerns about COVID-19 in the country (US Department of State 2020, 12).

Recommendations from civil society actors and medical specialists on improving the health sector include (Joarder et al. 2019):

- redesigning the Public Financial Management (PFM) system to mitigate inequalities in access to health care, do away with out-of-pocket-payments and achieve universal health coverage

- improving regulatory frameworks to decrease the costs of medicines and treatments. The private sector also needs adequate regulation for better management, improved quality and reduced costs.

- reforming the health insurance and finance system to fit the Bangladeshi context while being aware of its unique corruption challenges

- inter-sector collaboration so that civil society can consult and monitor without interference

- improving information and communication technologies (ICT) to enable adequate population coverage

- establishing and adhering to codes of conduct and operational protocols for service providers (including training for health workers)

- paying particular attention to marginalised and hard-to-reach populations with limited access to health care

- regular monitoring and evaluation

- enhancing health literacy and empowering communities to demand accountability in cases of fraud and corruption

With respect to the handling of the COVID-19 in the country, Julkarnayeen et al. (2020) note that transparency in expenditures (for example, in medical procurement), proper access to information and overall capacity enhancement are needed to improve accountability in the health sector.

Environment

Clause 18(Ka) of the Constitution of Bangladesh explicitly protects the environment for current and future generations. However, in practice there remains a considerable gap between climate change mitigation targets and fast-paced environmental degradation and the ever-increasing use of fossil fuels (TIB 2020, 3). By some estimates, the country could experience an annual loss to GDP of 2 per cent by 2050 and 9.4 per cent by 2100 due to climate change (ADB 2014). Millions of Bangladeshis live in low-lying coastal areas and are extremely vulnerable to climate change-triggered natural disasters (TI Climate Governance Integrity Programme 2018, 23). The World Bank (2021) overview for Bangladesh states that mitigating the country’s vulnerability to climate risks is necessary to protect its current growth and build resilience against future economic shocks.

Khan et al. (2013) note that the Bangladeshi climate finance landscape is highly complex and fragmented, complicating attempts at ‘keeping track of financial flows to understand who should be held accountable for decisions and results related to climate finance policy, allocation, disbursement and participation’ (2013). Transparency International Bangladesh (2020, 3) reports that various studies on climate finance management over a sustained period (2013, 2015, and 2017) have revealed lack of good governance, irregularities and corruption.

Both national and international actors have contributed to Bangladesh's climate funds (figures in 2020 stand at Tk 8.09 billion and Tk 120.91 billion, respectively) (TIB 2020). The Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund (BCCTF) is the key national body. International sources include, but are not limited to (TIB 2020):

- Global Environment Facility (GEF)

- Climate Investment Fund (CIF)

- Green Climate Fund (GCF)

- Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund (BCCRF)

The 2015 National Climate Change Mitigation Target ‘Nationally Determined Contribution’ (NDC), set in accordance with the Paris Climate Agreement, is Bangladesh’ chief environmental strategy (TIB 2020, 5). The plan’s main areas of focus are (TIB 2020, 5):

- climate mitigation technologies

- renewable energy, forestry and biodiversity conservation projects

- coastal forest boundaries to mitigate adverse impacts of environmental disasters

- adequate and efficient waste management

Recent programmes under the NDC are (Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change 2020, 3-5):

- Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan (up to 2030): mobilising investments (especially through international cooperation) for renewable energy and climate resilience initiatives

- National Solar Energy Roadmap, 2021-2041

- National Action Plan for Clean Cooking, 2020-2030

- Forest and Carbon Inventories

- Bangladesh National Action Plan (NAP) for Reducing Short Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs)

- Energy Efficiency and Conservation Master Plan up to 2030

- Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)/Carbon Trading

- Monitoring and Reducing Air Pollution

- Renewable Energy Initiatives

- Promoting Green Technology

The Renewable Energy Initiatives, in particular, requires at least 10 per cent of overall power generation in the country to come from renewable energy sources. The private sector is vital in implementing the programme. Bangladesh Bank has introduced a refinance scheme to support environmentally sustainable technologies such as solar energy, bio-gas plants, and Effluent Treatment Plants (ETP). The scheme has expanded to include 50 products under 11 categories such as ‘renewable energy, energy efficiency, solid waste management, liquid waste management, alternative energy, fire burnt brick, non-fire block brick, recycling and recyclable products, ensuring safety in work environment of factories’. The government has also rolled out a refinancing scheme to fund ‘alternative energy projects’ such as small-scale solar and micro grids to increase energy access in off-grid areas (Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change 2020, 5). Nest et al (2020, 4) point out that green transitions, however, require substantial inputs in construction, which as inherent corruption risks as a sector.

According to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (2020, 5, 7-8), around 11 per cent of the Bangladeshi population is receiving electricity generated by solar power and the government has installed close to 5.8 million solar-home systems across the country. The government aims to generate 1700 MW from utility-scale solar plants and 250 MW from solar home systems by 2030. There are also plans to establish bio-gas plants, especially in major cities due to high volumes of solid waste (Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change 2020, 8).

The latest NDC report by the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change does not discuss the use of fossil fuels. A 2019 report by Market Forces and 350.org, in collaboration with Transparency International Bangladesh, Waterkeepers Bangladesh and Bangladesh Paribesh Andolon, suggests that at least 29 coal-fired power projects with a total capacity of 33,200 MW are set to be constructed, which would increase the country’s coal power capacity 63-fold. The focus on coal-based projects is inconsistent with the Paris Agreement’s climate goals (Market Forces et al. 2019, 3).

Ecological threats

There are also ecological threats and corruption risks associated with planned coal-power projects. For example, despite public opposition and allegations of corruption in land acquisition and relocation processes, the Rampal power plant, which will generate 1,320 MW from coal, is currently under construction. The pollution from the plant would have a ‘devastating impact’ on the Sunderbans mangrove forest, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (Market Forces et al. 2019, 5).

A 2020 analysis by Transparency International Bangladesh of seven BCCTF-funded climate-mitigation projects found challenges related to governance, access to information, accountability and participation (especially with respect to marginalised communities and women). A few cases of corruption from the projects are listed in figure 4 below (TIB 2020, 9).

Table 2: Corruption and irregularities in climate projects analysed

|

Project |

Types of corruption |

Value of irregularities and corruption (in Taka) |

|

Project 1 |

40% of the 3.27 crore allocated for forestry has been embezzled |

1,31,00,000 |

|

Project 2 |

Vehicles and official equipment purchased under the project disappeared from the project implementational office and under-plantation (of about 100,000 saplings) |

56,25,000 |

|

Project 3 |

Embezzlement of allocated funds by showing full implementation of projects in paper but in reality, partial implementation of the project activities including plantation of substandard saplings. |

1,84,42,000 |

|

Project 4 |

About half of the allocated funds were embezzled by implementing only around 50% of the project work done in reality (while showing full work done in paper). |

8,66,00,000 |

|

Project 5 |

28% of the additional costs were added. |

55,90,200 |

|

Project 6 |

Exaggerated expenditure was shown on purchase of solar power equipment along with 4 acres of land at an additional cost of Tk 11 lakh per acre. |

23,44,00,000 |

|

Project 7 |

70% additional costs added. |

69,88,800 |

Source: Transparency International Bangladesh (2020, 9).

Government corruption has exacerbated environmental disasters and relief efforts in Bangladesh. For example, years of land grabbing, forest degradation and land settlements have increased environmental disaster vulnerabilities in hilly areas such as Bandarban, Chittagong Khagrachari and Rangamati (Gossman 2017).

As shown in figure 5, a 2020 analysis by Haque et al. of four projects related to the construction, renovation and maintenance of coastal infrastructures for disaster prevention found corruption siphoned off between 14 and 76 per cent of allocated funds.

Table 3: A snapshot of corruption in coastal infrastructure construction, repair, and maintenance

|

Project/Activity Type |

Corruption type |

Time-frame |

Total budget of the project (billion tk) |

Financial loss due to corruption (billion tk) |

Financial loss due to corruption (1%) |

|

Water management project |

Violation of public procurement law, lack of related experience and recruiting |

2011 |

9.75 |

1.4 |

14.36 |

|

Polder construction projects in Barguna and Patuakhali |

Embezzlement of money with a coalition of contractor and project officials |

2016 |

0.7203 |

0.1683 |

23.37 |

|

Manu river irrigation and pump house rehabilitation |

Embezzlement of project funds by influencing procurement process and collusion of contractor and project officials |

2019 |

0.5483 |

0.3442 |

62.78 |

|

Embankment construction at Koira of Khulna |

Embezzlement of money without completing the whole project work |

2020 |

0.0026 |

0.0020 |

76.92 |

Source: Haque et al. 2020, 15

Transparency International Bangladesh (2020, 3) notes that there is a lack of research on the implementation of environmental programmes. Nevertheless, there are best practices available from a pilot programme on climate fund governance in the country. These recommendations are grouped by their relevance to individual stakeholder groups (TI Climate Governance Integrity Programme 2018, 27-28):

International agencies:

- align sufficient funding with national and international policies and strategies

- build capacity for staff to implement projects in the country with effective prioritisation, access, delivery and monitoring of projects. Improve proactive disclosure of project information and agreements

- develop active coordination between public, private and civil society stakeholders.

Public sector:

- create multi-sector stakeholder forums involving the public and CSOs for decision-making, knowledge-sharing and meaningful participation

- design a distinct annual climate budget with a separate budget code for transparent reporting

- guarantee that social and environmental impact assessments are being conducted

- carry out scientific planning and assessment in coordination with the Ministry of Planning and the Ministry of Environment and Forests to prioritise vulnerability-based projects

- regularly update national strategies on environmental protection and climate change, and integrate these policies into the five national plans

- create a system for the online and offline disclosure of project documents, agreements, verifiable audits and monitoring reports

- introduce citizen-friendly complaints and a grievance-redress mechanism. Strengthen internal and external audit systems and establish independent monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, including community-led social accountability tools

- ensure that codes of conduct exist and are followed

Private sector (including national and international firms):

- employ climate-related technical experts (planning, financial) for effective decision-making in environmental projects

- adopt e-tendering and transparent procurement processes, and make efforts for proactive disclosure of information

- carry out meaningful consultations with stakeholders and project beneficiaries during the project formulation phase

- establish and use standard criteria for beneficiary selection to guarantee the protection of vulnerable communities

- compliance with environmental protection policies as well as findings of impact assessments

Civil society organisations (CSOs):

- focus on community-led adaptation projects

- empower local communities to lead accountability projects.

- create a platform for citizen grievances during impact assessments

- set up regular meetings with project beneficiaries and share monitoring and evaluation reports

In addition to conventional anti-corruption approaches that concentrate on formal mechanisms of transparency and accountability, Watkins and Khan (2021) propose two key methods for making climate change-adaptation funding more effective. Firstly. First, community leaders should spearhead anti-corruption monitoring to make it more effective. Second, adaptation projects should create real participation and optimise the involvement of the local families by being ‘dual use’, ensuring that communities benefit not only in the future but also the present, (for example, with embankments doubling up as new roads).

Nest et al. (2020, 10) state that maximising the results of climate mitigation interventions require sound governance strategies that ensure that climate funds are "not stolen, wasted, or directed to suboptimal activities – all problems caused by corruption."

Anti-corruption actors

The Bangladeshi anti-corruption climate is supported by a distinct legal framework and a range of institutional and civil society actors (Rahman 2019b, 11-13). However, combatting corruption is a challenge due to politicised enforcement and undermining of due process (Freedom House 2021a). The judiciary and law enforcement agencies are plagued by weak institutional capabilities, political interference and corruption, which contribute to a culture of impunity (GAN Integrity 2021).

Sustained political interference has rendered the leading institutional body charged with addressing corruption in Bangladesh, the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), largely ineffective (Freedom House 2021a). In 2016, the Commission’s mandate was formally weakened by an amendment that reauthorised law enforcement agencies, such as the police, to pursue cases of fraud, forgery and cheating under eight sections of the penal code (Rahman 2019b, 14).

The incumbent government continues to use the ACC as a tool to carry out corruption cases against political rivals from the previous regime of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) headed by the Khaleda Zia (Freedom House 2021a). Zia was jailed in 2018 on corruption charges and has been recently released on bail to receive medical treatment at home during the pandemic (Al Jazeera 2020).

After media reports, 24 local AL politicians and public officials were charged with corruption for allegedly stealing COVID-19 relief supplies meant for low-income communities (Freedom House 2021a; US Department of State 2020, 25).

Other laws such as the 2012 Anti-money Laundering Act largely remain ‘paper tigers’ and require adequate enforcement by enhancing the effectiveness and capacity of the country’s Financial Intelligence Unit (Iftekharuzzaman 2020).

Cautioning against an over-reliance on institutions to counter corruption, Mushtaq Khan, a prominent economist and academic, has instead highlighted the importance of coalitions in directing anti-corruption efforts (Nazrul 2021). Khan has argued that anti-corruption efforts start to work when a coalition of powerful actors, including but not limited to industrialists, businesspeople, investors, banks, exporters and buyers, wants rule enforcement in their area of work ‘not for the sake of the country but for their own interest’ (Nazrul 2021, Khan 2017, 39).

The Digital Security Act (DSA) of 2018, nominally enacted to reduce cybercrime, stipulates sentences of up to 10 years’ imprisonment for disseminating ‘propaganda’ against the ‘Bangladesh Liberation War, the national anthem or the national flag’ (US Department of State 2020, 3). A Human Rights Report by the US Department of State (2020, 3) notes that the DSA has been ‘widely used’ to crackdown on actors speaking against the government, especially in the context of issues related to the COVID-19 response.

Freedom of expression was also restricted by a 2020 circular from the Ministry of Home Affairs that threatens legal consequences for anyone spreading ‘false, fabricated, misleading and provocative statements regarding the government, public representatives, army officers, police and law enforcement through social media in the country and abroad’ (US Department of State 2020, 14).

The Bangladeshi global and internet freedom status is partly free according to Freedom House (2021a; 2021b). Reports Without Borders ranks Bangladesh 152 out of 180 countries in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index. Two journalists have been killed in 2021 so far. Reporters, media channels and CSOs are subject to government pressure, including but not limited to lawsuits, harassment and deadly physical attacks (Freedom House 2021a).

Local anti-corruption activists say sustained harassment from the government is curbing the effectiveness of CSO operations on the ground. For example, there are several cases of civil society actors being physically attacked for reporting on the COVID-19 crisis (Freedom House 2021b).

A few key anti-corruption CSOs include, but are not limited to, Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), SHUJAN – Citizens for Good Governance and Manusher Jonno Foundation (MJF). For details on active CSO actors, please refer to the paper onSocial accountability initiatives and civil society contribution to anti-corruption efforts in Bangladesh (2018). For details on the legal and institutional framework of the country, please refer to the Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in Bangladesh (2019).

Local civil society actors active in anti-corruption work include (please note that this illustrative and not exhaustive):

RMG:

- Bangladesh Centre for Workers’ Solidarity (BCWS) supports garment workers while advocating internationally and domestically for workers’ rights (BCWS 2021).

- Awaj Foundation is a women-led organisation with 22 offices and community centres across Bangladesh. It supports over 740,000 workers in major industrial sectors (especially RMG); raises awareness on the issues facing garment workers; trains workers on their rights and responsibilities under national and international legal frameworks; and builds their capacity to assume leadership roles and negotiate for better working conditions. All of their work aims to address gender inequity (Awaj Foundation n.d.)

Health:

- Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK) is one of the oldest registered non-profits in Bangladesh. It offers ‘community and institutional services in the fields of health care, women empowerment, disaster management, education, agriculture and basic rights-based advocacy’ (GK 2021).

- Centre for Development Innovation and Practices (CDIP) aims to improve the socio-economic status of disadvantaged families with the delivery of financial and social services and credit facilities (CPID 2021). These programmes also respond to health care needs (Bhuiya 2021).

- International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B) is committed to solving public health problems through laboratory-based, clinical, epidemiological and health systems research (ICDDR, B 2021).

Environment:

- Waterkeepers Bangladesh works to protect the water resources of Bangladesh, including its forest resources, through enforcement, fieldwork and community action (WKB 2015).

- Bangladesh Paribesh Andolon aims for ‘a nationwide, united and strong civic movement to protect Bangladesh’s environment’. The organisation also hosts a regular International Conference on Bangladesh Environment (ICBEN), which presents major environmental challenges and mitigation solutions (BAPA n.d.).

- Proshika hosts several environmental protection and regeneration programmes with a vision to create a ‘society which is economically productive and equitable, socially just, environmentally sound, and genuinely democratic’ (Proshika n.d.).

Annex 1

|

Focus area |

Corruption risks |

Entry points for reform |

|

Ready-made garments |

Kickbacks, bribery, bid-rigging, collusion |

Strengthening compliance with Accord and Alliance rules; improving workers’ rights; coalition building among key actors (businesses owners, manufacturers, suppliers, buyers exporters etc.) |

|

Health |

Procurement fraud, political interference, bribery |

Intersectoral collaboration with civil society; Enhancing regulatory mechanisms; Strengthening public health care capacity; Improving health literacy |

|

Environment |

Embezzlement, procurement fraud |

Ensuring proper environmental impact assessments; Empowering local communities; Transparency and monitoring of projects focused on the environment/climate |

- The transition was due initial to take place by 2024 but has been pushed to 2026 due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Dhaka Tribune 2021b).

- Rules of origin dictate the national source of a product. Since duties and restrictions often depend on the source of imports, such rules play an essential role in the flow of international trade (WTO 2021).

- Percentile rank showcases the country's rank among all countries under the aggregate indicator, with 0 relating to the lowest rank and 100 to the highest.

- The proportions of primary, secondary, and tertiary products that make up a country's exports.

- Bonded warehousing enables storage of goods that have not been processed by customs. The tax on such goods is paid upon sale, which in turn provides liquidity to businesses (Dictionary of International Trade 2021).

- Khan (2017) suggests that tackling corruption with ‘vertical enforcement’ is ‘implausible’ because ‘most influential organisations in the country are engaged in rule-violating behaviour or in informal contracting’ on a regular basis. In these contexts, ‘the 'horizontal' support by powerful organisations for the enforcement of the general rule of law’ is weak. In this context, anti-corruption laws are likely to be applied selectively to individuals and organisations currently out of favour with the ruling coalition. Khan states that such types of enforcement are not expected to achieve a general rule of law, and this is indeed what is seen across developing countries, including Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, Khan argues that despite a robust legal framework, anti-corruption implementation is weak and building technical expertise and combating systemic politicisation and corruption are necessary.