Introduction

The Nigerian Navy faces a wide range of grave security threats in its area of operations, including arms and drugs smuggling, human trafficking, oil theft, militancy, piracy, and potential terrorism (UNODC 2013). Given the strategic importance of the oil-rich Gulf of Guinea (GoG), the Nigerian Navy receives capacity-building training from the United States and European partner countries. However, corruption is rife within the Nigerian Navy, and the Navy itself has been accused of facilitating criminal activity, especially piracy and oil theft (Pérouse de Montclos 2012; Katsouris and Sayne 2013; Ingwe 2015).c79a9ce51b1c

There is little doubt that security institutions that themselves contribute to insecurity need professionalisation and assistance. If they do not receive it, they may remain weak and unfit to counter transnational and local threats. At the same time, efforts to provide these institutions with more capacity and skills may unintentionally aggravate corruption. Our paper investigates how the main capacity-building programmes run by the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM) deal with this dilemma. We take a close look at the role that anti-corruption measures play – and do not play – within these programmes, and make recommendations for a more effective approach.

Capacity building and corruption: A donor dilemma

Military assistance and capacity-building programmes have become a chosen tool in peace operations, stability operations, and development programmes.77cf4711ee3c These initiatives are typically intended to enable local security forces to tackle local and regional insecurity. The long-term objectives are to strengthen fragile states, keep transnational threats at bay, and prevent foreign security interventions from eventually becoming necessary.

For donors, an advantage of security assistance programmes is that they usually entail only limited efforts. They aim to build specific skills or to improve selected capacities of partner security institutions by providing training, mentoring, and/or equipment. Security assistance programmes should not be confused with security sector reform programmes, which are more comprehensive and have a stronger focus on good governance and institution building. In capacity-building programmes, the main goal is usually to improve particular tactical skills.

Compared to most other forms of military intervention, capacity-building programmes tend to be less resource-intensive, less lethal, and less controversial. Western donor states often have competing defence priorities, overstretched militaries, and war-averse electorates, which together make capacity-building programmes a popular tool. US security and military strategies explicitly recognise the value of these programmes. For instance, the 2011 National Strategy for Counterterrorism, the 2014 Quadrennial Defence Review, and the 2018 National Defense Strategy all point to building partner capacity and delivering security assistance as important elements of US national security policy.

When they are successful, security assistance, capacity-building, or train-and-equip programmes can benefit both the donor and the recipient. These programmes can potentially foster cooperation, improve interoperability, and help allies address shared security threats (TI UK 2015). However, the track record of capacity-building programmes is mixed at best. Despite their potential and popularity, the literature suggests that their effectiveness is often limited (Denney and Valters 2015). Capacity-building programmes may be inefficient and waste resources. Worse still, they may be downright counterproductive.

Providing security capacity building to weak states where corruption is pervasive may have a range of detrimental side effects. When such assistance is delivered without awareness of the political and economic incentives that exist within recipient institutions, there is a risk that it will stimulate corrupt or even criminal activity. Capacity building can strengthen the abilities of corrupt actors to devise corrupt schemes, as the skills and equipment provided may be used to “professionalise” corrupt practices. That is, security institution personnel may improve their abilities to divert resources away from the intended purposes. In the case of the Nigerian maritime security forces, satellite surveillance, improved vessels, advanced communication tools, intelligence-gathering skills, tactical skills, and so on may all serve the wrong cause if they are supplied to parts of the security apparatus that are involved in corrupt or criminal activity. By providing this type of training and equipment, therefore, donors can inadvertently buttress corrupt actors and further entrench corruption within security institutions. The end result may very well be more of the insecurity that capacity-building programmes are intended to reduce (TI UK 2015).

Security capacity-building programmes that ignore corruption can have even more far-reaching effects. For instance, they risk undermining the civilian institutions meant to control the security apparatus. In a worst-case scenario, they may fuel war, insurgency, or terrorism.5fdd401bc794 Recent history reveals many cases in which forces trained by, for example, the United States eventually turn into enemies of the donor country, using their newfound military skills to counter their old mentor.43ba81c8fcec

Despite these risks, the United States supplies various types of military aid to states both at war and at peace. According to one source, US forces and defence contractors are active in more than 125 countries, at an estimated price of $18 billion a year (Poe 2015). Many of these countries are plagued by corruption. According to data compiled by the Security Assistance Monitor, in 2016 the United States provided over $8 billion in arms and training to 50 of the 63 countries that Transparency International (TI) has rated as a having a high or critical risk of corruption in their defence sectors (Hartung 2016; Security Assistance Monitor 2017).

AFRICOM and capacity building

Our paper examines some of the most important capacity-building programmes that target the Nigerian maritime security apparatus. While the Nigerian Navy also has a presence in Lake Chad, we focus on capacity building aimed at strengthening operations in Nigerian territorial waters in the Gulf of Guinea. The main programmes reviewed here are the Africa Partnership Station (APS) and Africa Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership (AMLEP). Both are implemented by AFRICOM in cooperation with other partner countries with a view to helping African maritime security forces become better equipped to deal with regional security threats.

Established in 2007, AFRICOM is one of the United States Defense Department’s six geographic combatant commands. It is headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany, with an area of responsibility that covers all of Africa except Egypt. According to its mission statement, the “United States Africa Command, in concert with interagency and international partners, builds defense capabilities, responds to crisis, and deters and defeats transnational threats in order to advance U.S. national interests and promote regional security, stability, and prosperity” (AFRICOM 2018).In simple terms, the aim is to support and facilitate efforts by African nations to come up with their own solutions to security problems. This requires AFRICOM to work closely with African nations, the African Union, and African regional security organisations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). AFRICOM also cooperates with a wide array of other international partners, including nations from nearly every continent (interview, 31 October 2017).

The common objective of APS and AMLEP is to improve the ability of partner nations to extend the rule of law within their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones and to better combat illegal fishing, human smuggling, drug trafficking, oil theft, and piracy (AFRICOM 2017). APS is US Naval Forces Africa’s overarching capacity-buildingprogramme for Africa, aimed at improving systems and enhancing cooperation at the African regional level. AMLEP is an operational part of APS that works with African countries to target law enforcement at the national level.

In Nigeria, AFRICOM works closely with the Navy and other maritime security sector agencies. These include the Nigerian Maritime Police (NMP), a branch of the Nigerian police with jurisdiction in the territorial inland waters, ports, and harbours, and the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA), which is charged with providing port security and flag administration but which in fact functions much like a coast guard. Other Nigerian agencies such as the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA), and the Director of Public Prosecutions have specific maritime components. AFRICOM also works with other international partners in the country, such as the British High Commission (BHC). BHC involvement takes the form of training, advisory services, and mentoring at the operational, strategic, and management levels.3819be8d128f

Africa Partnership Station (APS)

APS is the maritime security cooperation programme of US Naval Forces Africa (NAVAF). Established in 2008, APS aims to build maritime safety and security by increasing maritime awareness, response capabilities, and infrastructure across African nations (AFRICOM 2018). It coordinates its activities through bilateral and multilateral agreements. The specific aims of APS are to increase maritime safety and security by strengthening the capabilities of partner naval forces through four “pillars”: (1) develop maritime domain awareness, maintaining a clear picture of the maritime environment; (2) build maritime professionals; (3) establish maritime infrastructure; (4) develop response capabilities while building regional integration.

To assist the coastal nations of Africa, including Nigeria, APS provides technological tools to detect and monitor criminal activity; practical tactical and operational training, delivered through joint exercises, port visits, and hands-on practical courses; and professional training and community outreach. To carry out these activities, the programme most often deploys a US or European partner country’s naval vessel to the region to serve as a floating classroom and training ground (Jenzen-Jones and Hutchins 2012). Mobile training teams comprise interagency and international trainers working with the US Navy, US Coast Guard, and agencies of partner nations. Since its inception, APS has progressed from a series of bilateral port visits to a series of regional training engagements ashore and at sea. The modus operandi of these programmes is training, including joint exercises, cooperation, and mentoring in real-world operations in the region (interview, 31 October 2017).

At the regional level, ECOWAS has been a recipient of AFRICOM’s maritime programmes in West Africa. The support provided through APS has helped ECOWAS work with national maritime agencies across Africa to build independent and collective capacity (interview, 26 October 2017).

Obangame Expressis an annual exercise conducted by NAVAF in the GoG.0d37ebc1b11c It is an “at-sea maritime exercise designed to improve cooperation among participating nations in order to increase maritime safety and security in the Gulf of Guinea.” The exercise includes maritime interdiction operations and practices such as visiting, boarding, and searching of vessels, along with evidence-gathering and seizure techniques (Jones 2014). It also covers training in medical response, radio communication, and information sharing across regional maritime operations centres. This joint approach led to success in 2015, when pirates seized the MT Maximus off the coast of Côte d’Ivoire. The oil tanker was tracked through the waters of at least four countries with close cooperation from all nations involved, including Nigeria, and was finally seized in Nigerian waters. The crew were freed and some of the pirates apprehended (Herring 2016).

Africa Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership (AMLEP)

AMLEP is a law enforcement training programme that enables African partner nations to build maritime security capacity and improve management of their maritime environment at national level. AMLEP’s work with each partner nation comprises five phases: legal risk assessment, training, exercises, operations, and sustainment.

In the legal risk assessment phase, AFRICOM develops a legal interoperability agreement between AFRICOM and the partner nation(s). A team of Coast Guard attorneys, audit staff, and operational experts conduct scoping exercises to assess the particular legal and operational environment prior to drafting the agreement. This process can present challenges, because not all organisations within a given nation will have a similar interpretation of its laws and policies. There needs to be detailed research and discussion in country, going beyond what is written in legislation and policy. For example, although many nations have signed international conventions, some may have implemented them only partially or not at all. In other cases, agencies have institutionalised practices that have no legal basis (interview, 31 October 2017).

AFRICOM will not enter into agreement with a country unless the appropriate laws are in place (interview no. 16, 31 October 2017). The process of reaching an agreement is elaborate and reflects AFRICOM’s awareness that legal and administrative practices are limited in some partner countries. Moreover, AFRICOM has baseline standards that must be met before the agency will implement its programmes. That said, while AFRICOM conducts a scoping exercise of the operational environment, it does not necessarily seek to address all issues uncovered during this phase, either prior to or during the programme. A case in point is Nigeria, where a scoping exercise would most likely have revealed extensive allegations of corruption.

As in the case of APS, a mobile US training team usually provides the training under AMLEP. This can take place in the partner nation, elsewhere in Africa, and/or in the United States.Operation Junction Rain is the name given to the fourth phase, also known as the “real-world operational phase,” as it is not a training exercise. For this phase, participating nations agree to have personnel of other agencies on board their vessels (if suitable vessels are available) in a partnership capacity (interview, 31 October 2017). Such agencies have most frequently included the US Coast Guard and the US Navy, but have also included other national and international partners. For example, one nation has included national anti-corruption professionals in their boarding teams to ensure transparency, openness, and good practice on board vessels.507ce038c8d6 US teams operate on board to advise and assist the host nation’s teams. Finally, the sustainability phase aims to maintain the positive developments achieved during the earlier phases and supports the sharing of skills and expertise between agencies.

Methodology

This paper was guided by the following research questions: Do AFRICOM’s main capacity-building programmes address corruption in the Nigerian Navy? If so, what measures are put in place, and how are they designed to safeguard against the possibility that in an environment where corruption is pervasive, the programmes will do more harm than good? If anti-corruption measures are absent, why is this issue not addressed, and what are the implications of this omission?

The methodology for this study comprised desk-based research, in-country interviews, and expert reviews of the analysis. A literature review was conducted with open source material. This involved a comprehensive search and selection of relevant documents based on scope, relevance, credibility, and completeness.

Given the general lack of transparency regarding military assistance programmes in the United States (Hartung 2016),a2e5cb482afb the bulk of the empirical material used for this paper comes from interviews conducted in Nigeria. Fifteen interviews were held in Abuja and Lagos between 23 and 29 October 2017. A further three interviews were conducted by phone and in person in London in early 2018. The interviewees included representatives of government agencies, civil society organisations, and the international diplomatic and donor community.1ba10efbd10b Prior to publication, the paper was peer-reviewed by three experts to ensure accuracy, logic, and relevance. AFRICOM did not respond to a request for comment.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. We first briefly describe the security challenges that the Nigerian Navy faces in the GoG and summarise what is known about the impact of corruption on that situation. Next, we consider how capacity building addresses (or does not address) corruption in the Nigerian Navy. The final section provides some recommendations for donors engaged in capacity building of the Nigerian maritime security forces.

Corruption and insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea

Capacity-building programmes that aim to improve the highly insecure situation in the Gulf of Guinea face a complex challenge. First, the extent and gravity of criminal activity in Nigerian territorial waters is daunting. Second, Nigerian maritime security governance in the area is weak and the security apparatus is not fit for the task.

The larger GoG is an area of high maritime economic activity. It holds large reserves of energy resources, and its ports are key to both the Nigerian economy and the international maritime transportation network. At the same time, the Gulf faces a wide spectrum of security challenges and is often described in the media as lawless. The region is a hub for transnational criminal groups and for local militants. The Nigerian part of the GoG, in particular, is a transhipment point for trafficking in drugs, migrants, and weapons, as well as a hotspot for piracy, illegal oil bunkering (another term for oil theft), and illegal fishing. In recent years, Nigerian territorial waters and the Nigerian Exclusive Economic Zone have become one of the world’s most dangerous areas for violent piracy and armed robberies. According to the International Maritime Bureau, the statistics for the first quarter of 2018 showed Nigerian piracy as a worsening problem, with an increase in hijackings and kidnappings. Of all instances worldwide in which ships were fired upon, two-thirds occurred in Nigerian waters (ICC IMB 2018).

This is not a new situation, as between 2007 and 2016 there were an average of 87 pirate and pirate-related attacks in Nigerian waters each year.e80ba2537882 This number includes successful and unsuccessful hijackings, kidnappings, robberies, and thefts (Steffen 2017). Hijackings of the kind seen in the Gulf of Aden in the past have been rare, but attacks aimed at looting cargoes or kidnapping individuals for ransom have become more frequent (UNODC 2013; ICC IMB 2018). Kidnappings are often coupled with the petroleum-related violence on land in the Niger Delta that is typically the work of Delta militants (Hastings and Phillips 2015; Obi and Rustad 2011; Bøås 2011). This shows a certain collusion between different types of illegal activity. In fact, Delta militants have been known to engage in maritime crime during periods of low activity in militancy, illegal oil bunkering, or gang warfare on land (Bøås 2011).

The larger GoG has become an important transit point for cocaine and other illicit goods. The region is also rife with many forms of environmental crime and petty crime (UNODC 2013). The high level of maritime insecurity in the region directly affects international commercial interests – shipping and the oil and gas sector in particular. It is also a serious economic drain on local economies, especially the oil-dependent Nigerian economy.a7e9074bb77fThe unstable situation in the Delta and in the Nigerian part of the GoG has come to represent a political threat to the fragile state, a major security problem in the region, and a matter of international concern.

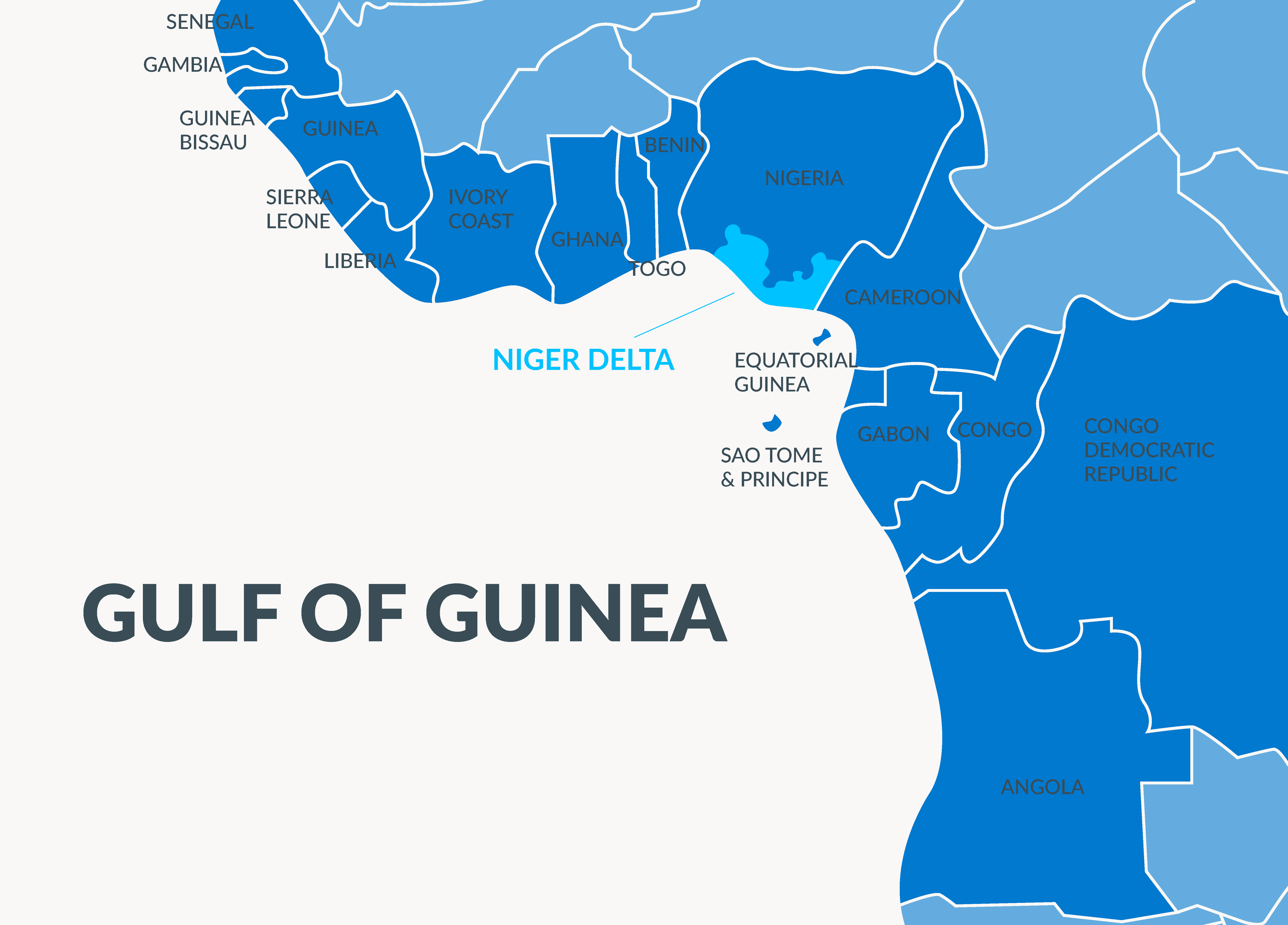

Gulf of Guinea, west Africa, showing the Niger Delta.

The Nigerian Navy’s capacity to counter crime and insecurity

Corruption is widely considered to be pervasive at all levels of the Nigerian government (Bøås 2011; Oarhe 2013; U4 2014).Nigeria has even been described as a “structured kleptocracy” (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2014), and as a society where the networks involved in corruption are vertically integrated. Corruption manifests itself as large-scale embezzlement of public funds, but also as administrative corruption affecting the day-to-day running of the public sphere and the lives of ordinary Nigerians. A recent household survey conducted by the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) revealed that Nigerian public officials show little hesitation in asking for bribes. A third of Nigerian adults who had been in contact with a public official had paid a bribe to that official during the period covered by the survey (UNODC 2017).

The fact that corruption in Nigeria is systemic means that large parts of entire state sectors, such as parts of the security apparatus or government departments, are embedded in networks that engage in resource extraction for private gain. This does not, however, prevent them from at the same time performing their official functions, at least to some extent (Stridsman and Østensen 2017).

Systemically corrupt societies often shield corrupt officials from ever being convicted for their acts. In 2017, Nigerians considered the police and the judiciary (judges and lawyers) the two most corrupt institutions in the state apparatus (UNODC 2017). High levels of corruption within these institutions mean that senior officials are rarely punished for corruption. For instance, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) has been able to build cases against some senior officials and members of the elite, but most often these cases make little progress in the courts.

Corruption also heavily affects the Armed Forces and the security institutions in Nigeria. According to a 2015 index of corruption risk worldwide, Nigeria’s defence and security sector falls in one of the highest risk categories (TI-DS 2015). Another recent TI report concluded that corruption has been particularly destructive in that sector, hollowing out the Army and compromising the integrity of the Navy (TI-DS/CISLAC 2017). In fact, corruption penetrates all military branches and institutions and infests the entire military chain of command, as well as the political apparatus, including legislators and other government officials (ICG 2016).

While corruption within the Armed Forces is not new, a drop in Nigerian oil revenues since 2014 has aggravated it. Corrupt elites have increasingly moved to raid defence and security sector budgets to maintain their patronage structures (TI-DS/CISLAC 2017). In the process, they have taken over defence budgets, including defence spending and procurement, and even senior military posts. This has led to a situation described by TI as a “kleptocratic capture of the defence sector” (TI-DS/CISLAC 2017, 9). This takeover has in turn facilitated massive fraud and embezzlement, especially through inflated procurement contracts and phantom defence contracts (TI-DS/CISLAC 2017). The same report holds that former military chiefs have stolen roughly $15 billion through procurement-related fraud.

The defence sector has not only suffered from corrupt looting; it has also been subject to chronic under-resourcing for years. The downward spiral started during the 33 years of military dictatorship, with detrimental effects on professionalism, operational efficiency, and accountability. Since then there have been persistent failures to bring the forces up to standard. Indeed, lack of efficient reforms combined with funding constraints have transformed the Nigerian Armed Forces from one of Africa’s strongest militaries to a body in distress (ICG 2016).7a9fc3901373 The Nigerian Navy, least on paper, is one of the biggest in Africa. It is, however, in a relatively poor state due to corruption and the general decay that has affected the entire Nigerian Armed Forces for decades.

Chronic lack of maintenance and failure to repair vessels and equipment (Nkala 2015) along with poor training and recruitment procedures have crippled naval security institutions. “Cannibalisation” by corrupt officials, constant shortage of resources, and lack of maintenance have negatively affected the morale of the Nigerian security forces overall (TI-DS/CISLAC 2017). Consequently, low morale and low prestige associated with working in a deprived and inefficient Navy may contribute to the propensity for naval officers to engage in corrupt behaviour.

In 2015 the chief of naval staff, Vice Admiral Ibok-Ete Ekwe Ibas, the highest-ranking officer in the Nigerian Navy, complained that most of the Navy’s operations designed to eradicate the oil bunkering syndicates were achieving only limited success because some personnel were themselves involved in the illegal activities (Nkala 2015). Several empirical studies have confirmed this tendency. These studies in general report that naval officials have been taking bribes, covering up illegal activities, diverting resources intended to fight criminal activity, and providing direct assistance to criminal actors (see, e.g., Katsouris and Sayne 2013; Pérouse de Montclos 2012; TI-DS/CISLAC 2017).

In a 2013 study, Katsouris and Sayne found that the Joint Task Force77ffd7458014 and the Navy, the two main law-enforcement bodies tasked with combating oil theft, were themselves heavily involved in facilitating medium- and large-scale illegal bunkering (see also Pérouse de Montclos 2012; ICG 2016; Ingwe 2015). Networks involved in large-scale bunkering are reportedly obliged to pay a fee to the Navy for free passage in coastal waters (Pérouse de Montclos 2012). Similarly, complex networks of actors facilitate oil theft at sea. These networks include state institutions such as the naval forces as well as institutions of the formal economy, along with a diverse set of national and international criminal groups (Hastings and Phillips 2015).

There have been reports that the Navy, customs, and port authorities on occasion inform pirates and militants of the locations of ships and their cargo. Pirates have even been handed bills of lading for target ships, providing them with exact details of the potential loot (Pérouse de Monclos 2012). In this way, corrupt elements of the maritime security forces facilitate and protect pirate attacks and oil theft at sea.

Faced with the high levels of maritime attacks and piracy described above, many international shippers have hired private protection for their ships when in the GoG. However, according to Nigerian law, armed private security details are not allowed on board commercial ships (INTERTANKO 2017). In order to circumvent this restriction and meet the demand for private protection of ships, Navy personnel have often supplied vessel protection in conjunction with private security companies. This arrangement represents an increased risk of corruption (see, e.g., Steffen 2014).

Because of the poor condition of naval vessels, the Navy has leased privately owned patrol vessels, which operate according to the rules of engagement established for private security companies. In 2016, a memorandum of understanding allowed 16 private security companies to enter agreements with Nigerian authorities to supply and maintain vessels manned with Nigerian naval personnel or with a mix of private operators and Nigerian Navy service members (Maritime Executive 2016). These vessels receive Nigerian Navy pennant numbers, but they operate outside the administrative and logistical infrastructure of the Navy (INTERTANKO 2017). When not on official duty, these patrol boats and crews are often hired by commercial clients as protective escorts (Steffen 2017).

As the fleet of privately contracted security vessels now counts more than 100, controlling and monitoring the activities of these armed vessels has become a challenge (Steffen 2017). The arrangement also carries considerable risk for abuse and provides many opportunities for corruption and criminal activity.

Similarly, both the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) and the Navy have relied in the past on private companies to render some of their services (Steffen 2014). The involvement of these actors complicates oversight of who does what, and under whose authority, within the Nigerian maritime security domain. This in turn complicates donors’ efforts to provide targeted training and capacity building in this sector. For example, under a government amnesty programme for Delta militants, NIMASA has relied on Global West Vessel Specialist Ltd., an entity controlled by militant leader Government Ekpemupolo (“Tompolo”). This relationship has led to a corruption case involving a range NIMASA’s top officials (Reuters 2016).

All in all, the problem of corruption is deep-seated within the Nigerian maritime security forces. Corrupt officials in high positions undermine security governance by stealing the funds that should have been used to run maritime security institutions. In addition, a multitude of corrupt behaviours within these agencies serve to facilitate or protect criminal activities. In the most extreme cases, there is a degree of collusion between criminals and security officials whereby security forces not only facilitate crime but help organise it, or even carry it out themselves.35ec6daa1a2c

Corruption has contributed to creating an inefficient and unreliable Nigerian naval force that allows maritime insecurity to persist. Consequently, any donor seeking to enhance the capacity of these forces should be highly attentive to the devastating role played by corruption.

That said, there has been a change in Nigeria’s approach to corruption under the presidency of Muhammadu Buhari. Since coming to office in 2015, he has pledged to “make governance in Nigeria more open, accountable and responsive to citizens,” and he has introduced several important reforms and initiatives (OGP 2016). The government joined the Open Government Partnership (OGP) in July 2016. The OGP National Steering Committee of Nigeria has developed a Nigeria National Action Plan (2017–2019), which aims to “deepen and mainstream transparency mechanisms and citizens’ engagement in the management of public resources across all sectors.” Despite Buhari’s apparent commitment, there are few quick fixes for systemic corruption, and Nigerians’ perceptions of corruption have remained gloomy since Buhari assumed power (TI 2018).

Do capacity-building programmes address corruption in the Nigerian maritime security sector?

Knowing that corruption has been debilitating to the maritime security institutions in Nigeria, we have studied how anti-corruption measures are incorporated – if at all – into the different phases and aspects of the two AFRICOM programmes described above, ranging from classroom training to exercises and real-world operations. Our findings suggest that neither programme has an explicit anti-corruption component. None of our interviewees offered a specific reason to explain this omission, though they acknowledged that corruption is a significant problem in Nigeria.

It is very difficult to get information on specific support given to nations by AFRICOM, especially information relating to ASP and AMLEP. The timeline in Box 1 provides examples of Nigeria’s participation in these programmes.

Box 1: Nigerian participation in AFRICOM programmes

2010

- APS conducted 10 engagement activities, such as port visits, in seven countries: Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Senegal.

2011

- Nigeria, along with Ghana and Senegal, emerged as critical partners in efforts to enhance stability and security in West Africa.

2012

- Benin and Nigeria began joint maritime patrols. APS constructed a “training African trainers” programme to enable African maritime forces to provide the same level of instruction without using US personnel. APS engaged with 21 nations and trained more than 7,700 maritime security professionals.

2013

- African maritime forces used skills gained through participation in AMLEP and APS to conduct operations that resulted in the seizure of over $100 million worth of cocaine and the levying of over $3 million in fines.

2014

- Obangame Express was conducted off the coast of Cameroon and Nigeria, with most ships moving from the port of Lagos.

2015

- AFRICOM conducted a range of bilateral efforts, preparing to expand engagement as security and partner capacity allow.

- Nigeria again participated in Obangame Express. The joint high-speed vessel USNS Spearhead (JHSV 1) and its detachment of US Navy sailors, civil service mariners, and US, Spanish, and British Marines functioned as a platform for Nigerian and Cameroonian forces to simulate maritime interdiction boarding as part of the interoperability exercise.

- Nigeria participated in the week-long Combined Force Maritime Component Commander (CFMCC) Flag Course, which was held by the US Naval War College at Naval Support Activity Naples, a US Navy complex in Italy. Thirty-three senior naval leaders from maritime countries in Europe and Africa attended.

2016

- Law enforcement teams in the GoG, from Nigeria and other nations, conducted 32 boardings that resulted in more than 50 maritime violations ($1.2 million in fines levied). These included the first-ever takedown of the pirated tanker MT Maximus through an opposed boarding. Nigerian teams were directly involved in this incident, in which 18 crew member lives were saved.

2017

- Nigeria’s chief of defence staff visited AFRICOM, Stuttgart, for a programme designed to reinforce the importance of strong US-Nigeria security cooperation relationships; topics included maritime security in the GoG.

- Obangame Express had a component in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. This involved the Nigerian Navy ships Okpabana, Centenary, and Sagbama and one helicopter, along with a French Navy ship, Jacoubet.

Lack of evidence of capacity building’s impact on corruption

It is unclear whether and how, if at all, capacity-building activities have affected corruption, for good or ill. No interviewee reported that their agency audited the use of the skills or training provided at end of the programme to ensure they were being used for the intended purpose and in the intended way. That said, the APS and AMLEP programmes do include a number of elements that monitor skills learned and their application in the real world, which provides some level of assurance that learned skills are not being misused.

However, this lack of detailed auditing, coupled with the absence of anti-corruption components in the programmes, is significant, especially in light of the specific risk associated with train-and-equip programmes that do not have specific anti-corruption components, as noted by TI. Such programmes risk enhancing the ability of recipient organisations to engage in corrupt practices, insofar as “knowledge and equipment can be diverted or misused for factional or private gain” (TI-DS 2017, 53). It is extremely difficult to determine whether this is in fact happening, given the lack of empirical research on the presence, types, and mechanisms of corruption within the Nigerian Navy, as well as the lack of detail on specific capacity-building programmes in this sector. This is compounded by a lack of transparency in the security sector in general.

Safeguarding programmes by corruption-proofing procurement

Despite the absence of explicit measures to reduce corrupt practices in the maritime security sector, AFRICOM does consider the risk of corruption with regard to implementation of its own programmes. Strict anti-corruption measures are present in the design and implementation of these programmes to safeguard them against corruption. For example, AMLEP’s legal risk assessment phase helps reduce opportunities for corruption at the implementation stage by including a comprehensive review of the environment in which activities will take place. All partners sign MOUs that outline what has been agreed.

This approach is not unique to AFRICOM’s capacity-building programmes. Representatives from the British High Commission, which also provides capacity building in the Nigerian maritime security sector, noted that while its programmes do not include anti-corruption components, they are designed in such a way as to guard against misuse of programme funds (interview, October 2017). This rigorous protection of donor funds is in stark contrast to an apparently conscious exclusion of broader anti-corruption provisions from such capacity-building initiatives.

Other donors involved in capacity building in Nigeria echoed the approach of AFRICOM and the British High Commission. For example, the European Union (EU) Delegation noted that while they offer specific anti-corruption programmes, which include anti-corruption and procurement training, their programmes on other topics do not have specific anti-corruption components (interview, October 2017). This approach was confirmed by recipients of capacity-building assistance. To prevent misuse of their funds, many donor organisations do not give financial support directly to recipient organisations, but instead favour technical support and operational training. Where procurement projects are required, they make use of the donor’s internal procedures. The EU conducts detailed reviews prior to finalising its own capacity-building programmes, but they do not use this information to shape practical anti-corruption support.

Some international organisations, such as the European Union, use third-party implementing bodies, such as the British Council, to reduce opportunities for malpractice. These entities can be national or international, and their selection is based on the presence of expert skills and experience in the necessary areas (interviews, October 2017). The financial procedures for such parties are usually governed by the financial procedures of the purchasing organisation, but in some cases the financial procedures of the third party are used if they meet the same standards. The United States Embassy in Nigeria noted that they also closely audit programmes, including conducting an annual audit of equipment provided to make sure it is being used for the intended purpose.

The concern with providing finance directly to agencies in Nigeria is not unique to the maritime security sector. There is a shared perception that corrupt practices are very prevalent and well organised throughout Nigeria. As a result, organisations working in many sectors prefer to avoid providing direct financial support.

Reasons for not directly addressing corruption in capacity building

Interviewees offered five main explanations as to why capacity-building programmes appear to sidestep the corruption problem. First, some claimed that the programmes do not address corruption because the training and operations involved do not typically lend themselves to this purpose, being largely hands-on, operational, and skills-based in nature. AFRICOM is a tactical and operational command, and AMLEP and APS are largely focused on achieving an operational effect, not necessarily driven by strategic thinking. This is reflected in the rank of those conducting the training: while these mid-ranking personnel may be good at their jobs, they are often risk-averse and cautious about things going wrong (interview, 4 May 2018).

Second, the international community negotiates capacity-building programmes and activities with national authorities, and while donors may not make a strategic decision to avoid the field of corruption, interviewees acknowledged that corruption is a politically sensitive topic that needs to be handled with care. Nevertheless, such topics are not beyond the scope of international support in Nigeria. Progress has been achieved in tackling sensitive issues, including corruption, within the realm of security and defence. This is evidenced by ongoing programmes of Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS), the UK government, and the US government through its Security Governance Initiative. These programmes illustrate that governments, specific ministries, and related agencies are open to these kinds of initiatives when donor communities frame them differently. However, our research did indicate an apparently conscious exclusion of anti-corruption initiatives from the objectives and mandates of APS and AMLEP. Exactly why this was the case is unclear. There was no suggestion that the Nigerian Navy itself explicitly rejected the inclusion of such measures in the programmes.

Third, AFRICOM works on a short-to-medium-term operational and rotational cycle that often results in a relatively quick turnover of staff. This does not allow for longer relationship building and buy-in from the necessary stakeholders, as trust has to be developed every time new personnel arrive.

A fourth challenge raised by interviewees relates to difficulties in implementing aspects of training or good practice when necessary infrastructure is limited or absent. For example, the port infrastructure in Lagos is ill-equipped to manage in a timely manner the large volume of cargo coming through the port. This can provide motivation for payment to secure speedy clearance, thereby increasing the opportunity for corruption. Capacity building is unlikely to influence such behaviour without capital investment to improve the port. Such challenges are significant, given that about 90 percent of commerce enters Africa by sea(Business Tech 2015).

Considerable work is being done on Nigerian ports, aimed at upgrading infrastructure and establishing transparent procedures and timelines, coupled with regular audits. Such improvements are important, as better commercial standards and procedures are likely to result in a higher demand for professionalism in the maritime security sector, given the close cooperation between civil and security sector agencies in this area. However, they could also provide more opportunity for corruption. These efforts are mirrored in other countries in the GoG. It is planned that similar projects will give West African ports the ability to handle about 11.5 million additional shipping containers by 2020 (Africa Defense Forum 2015).

Finally, it can be challenging to enlist suitable participants for capacity-building activities in any sector – those with the right skills, aptitude, willingness, and experience for the jobs they are required to do. Host nations usually select the participants, often without an assessment or vetting of their suitability. This can limit the impact of the training.

Furthermore, given the size of Nigeria, participation in courses often entails considerable travel costs. These are meant to be paid by the host nation, but in some cases they do not reimburse participants, which can deter them from returning for future training, as well as discourage new recruits.

It was also reported that some of the capacity-building programmes are targeted at the professional arms of organisations, which are much less susceptible to corruption and thus less in need of anti-corruption training. The Special Boat Service within the Nigerian Navy was identified as one such unit: it is reportedly well led for the most part and has a different culture from the rest of the organisation, leaving it less vulnerable to corruption (interviews, October 2017).

Broader implications: Doing harm by looking away

Transparency International emphasises that corruption is not yet treated as a critical concern at the top level of foreign and security policy across countries – but should be (TI-DS 2017, 52). The situation in capacity-building programmes in the maritime security sector in Nigeria bears this out.

In fact, the only organisation found to be engaging in this sector with targeted anti-corruption capacity-building programmes is Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS). This initiative is still in the early stages. Progress is most significant with the Nigerian Air Force, where a recent leadership change appears to have increased political will within the agency to improve its processes and procedures. Work is under way to develop an anti-corruption road map for the Air Force and to conduct an internal corruption risk assessment. TI-DS has made similar outreach to the Army and the Navy. Progress with the Army has been slow, likely influenced by the Army’s involvement in the ongoing insurgency in the northeast Nigeria. There is as yet no concrete engagement with the Navy.

AFRICOM and other capacity builders are not blind to the prevalence of corruption in Nigeria. They clearly avoid, whenever possible, providing direct financial support to Nigerian partners, and they have established stringent protocols to safeguard against corruption in project implementation. The current AFRICOM approach to corruption thus resembles the very narrow and short-sighted interpretation of “do no harm” common to many international support programmes operating in fragile contexts: that is, to focus on safeguarding the programme funding.

A widely cited principle of human medicine, attributed to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, is “First, do no harm.” This has been interpreted to mean that doctors should refrain from treating an illness if there is a risk that the intervention will do more harm than good to the patient. This nostrum was incorporated into development policy about ten years ago (OECD 2010). While many donors have formerly adopted this principle, they have problems operationalising it, especially in fragile settings. Johnston and Johnsøn found in a 2014 survey that most aid agencies’ implementation of “do no harm” involved protecting their own funds from corruption; they were not mainly concerned about preventing government capture of anti-corruption initiatives or avoiding anti-corruption reforms that might overwhelm a society’s capacity to absorb aid.

Interviewees for our study highlighted the corruption-proofing of programme procurement, but we found no evidence that anti-corruption efforts have gone beyond that. Given this limitation, there has been no risk that anti-corruption initiatives will be captured or will overwhelm society’s absorptive capacity. The risk, rather, is that by professionalising corrupt personnel in the security sector, capacity building will heighten the risk of more professionalised corruption.

The relative inattention to corruption confirmed in our study seems to suggest a view that one can build capacity first, and then (perhaps) deal with corruption later, or even leave anti-corruption efforts entirely to organisations and agencies dedicated to this purpose. It seems to suggest that security institutions can be simultaneously effective and corrupt. However, systemic corruption directly undermines military readiness and force deployment. This can already be seen in northern Nigeria, where the Nigerian Army is waging a fight against the Boko Haram insurgency (see, e.g., TI-DS/CISLAC 2017). In fragile environments, we argue, donors, implementers, and policy makers should increase their awareness of the potential negative effects of corruption and should make anti-corruption a key component of the design, implementation, and follow-up of military training.

Despite the practical difficulties and political delicacy of addressing corruption, much more can and should be done to incorporate anti-corruption components into capacity-building programmes in the maritime security sector in Nigeria. Failing this, there is a real risk that capacity-building interventions could be used to encourage and facilitate corruption, given the pervasive corruption associated with maritime security in Nigeria. Strengthening military capability without strengthening controls and checks and balances may come with a high risk. That said, even where anti-corruption measures are integrated into capacity-building programmes, they are likely to have impact only when they are aligned with a wider strategy to strengthen integrity within the Armed Forces.

Recommendations for future international support to the Nigerian Navy

AFRICOM cannot afford to ignore corruption. In the case of the Nigerian maritime security sector, widespread petty corruption poses a risk that resources will be wasted or diverted at the tactical and operational levels. Even more seriously, as examples provided in this paper have shown, corruption may help fuel the crime and violence that the security agencies are intended to fight.

While we recommend that anti-corruption measures be included in AMLEP and APS, it is important to note that the capacity-building or train-and-equip programmes provided to selected institutions in partner countries do not have the potential to rid any security sector of corruption. In order to reduce corruption significantly, much more comprehensive and long-term governance reform efforts targeting all sectors of government would be necessary, although certainly no guarantee.

The next regular review of Nigerian defence policy is due in 2018. In the context of this review, the clear hierarchy and chain of command in the security sector provides an obvious entry point for an anti-corruption strategy: at the top. As long as senior Navy personnel do not wholeheartedly support the cleaning up of the sector, any attempts to induce junior staff to adopt anti-corruption practices will be in vain. At the same time, senior Navy personnel may be caught in their very own “prisoner dilemma,” risking their careers and the Navy’s reputation if they take steps to restrain or report illegal income generation by others. Even at the highest level, there might still be a collective action problem, especially given the entrenched system of political patronage, favours, and kickbacks. A collective commitment to overcome this problem in the context of a new or revised defence policy would be a major step forward.

Donor efforts to professionalise security personnel in partner countries should include anti-corruption measures tailored to the respective security institutions and their particular corruption risks. Still, simply adding anti-corruption packages to the mix of lectures is unlikely to have a fundamental effect. Instead, initiatives to reduce corruption should be part of all training and capacity building, whether theoretical or practical. In order to devise effective anti-corruption measures, donors should specifically consider whether capacity-building efforts will likely translate into institutional improvements or will instead create “capital” that may be attractive to corrupt actors, subversive forces, or disloyal individuals.

One of the main recommendations for Nigeria in Transparency International’s 2015 government defence anti-corruption index is to “reduce military predation and build the integrity of the armed forces.” This suggests that reducing corruption is fundamental to improving the performance of the security forces overall. It also means that if one is to provide effective training and capacity building to the Nigerian maritime security institutions, anti-corruption measures should be an integral part of such efforts. Following is a list of ways in which anti-corruption components could be incorporated into capacity building of the Nigerian maritime security forces.

List of recommendations

1. Create awarenessof the potential impact of corruption on capacity building

- Recognise that corruption can undermine the results of security assistance programmes. Inform donors and implementors of this risk, emphasising that capacity building without anti-corruption measures can bolster subversive or criminal forces.

- The Open Government Partnership may provide a positive avenue for raising awareness and opening discussion with the Nigerian government. While the OGP has not singled out specific governmental services, the Navy should be encouraged to proactively implement reform in this area.

2. Avoid compartmentalising “security” and “corruption” into two unrelated issues

- Embed anti-corruption strategies into capacity-building programmes

- Engage with political leaders and the heads of government services to help create conditions amenable to positive change.

3. Assess corruption risks and develop mitigation plans

- Assess the levels and types of corruption present in the Nigerian maritime security apparatus. This process should be peer-reviewed by either local experts or international experts, or both, to ensure objectivity and independence. Develop a corruption risk assessment that is based on both internal and external assessments.

- Acquire knowledge of what specific institutional weaknesses (if any) affect specific partner institutions. For example, if corruption or nepotism is influencing recruitment or promotions within an institution, this should be taken into account when selecting the personnel to receive training.

- Make sure that developing and implementing anti-corruption measures becomes part and parcel of the institutional learning itself. For instance, support the Navy to conduct an appraisal of what needs to be done in these areas. Assist with developing anti-corruption action/ mitigation plans tailored to the specific risks identified within the specific sector, remaining aware of the need for more wide-ranging efforts that encompass the entire security sector in Nigeria.

4. Provide pre-deployment training to donor staff

- Provide guidance to tactical trainers on how to include anti-corruption and integrity components in capacity building.

- Develop tools that staff can use to recognise and mitigate corruption. Carry out pre-deployment training on how to recognise and mitigate corruption when teaching, in exercises, and in operations.

- Build on extant knowledge and resources. Lessons learned in other operations, security sector reforms, state-building efforts, and capacity-building programmes may be relevant to several contexts.2e5d1a9dc658

5. Provide integrated anti-corruption training to partners

- Incorporate anti-corruption measures into doctrine, policy, and plans. Include corruption as an element in training, exercises, tactical guidance, and field guides and manuals.

- Identify needs for training, communication, and codes of conduct. Provide support for their planning, development, and implementation.

- Include lessons in military integrity, values, ethics, and ethos as a natural part of classroom training, to be followed up in exercises.

- Introduce structured and integrated anti-corruption training for all levels from point of initial contact, rather than providing this training as separate packages or modules.

- Help build new mindsets among the top and middle military leadership through corruption-prevention training (see, e.g., Pyman 2017), notably when “building maritime professionals” through APS. This is crucial insofar as much capacity building relies on a train-the-trainers strategy, meaning that the local personnel trained should later function as trainers and pass on both theoretical knowledge and tactical skills.

- Provide training to military commanders at military academies in Nigeria as well as in partner military academies that host military personnel from Nigeria.

6. Monitor the assistance and safeguard against abuse

- Monitor and track assistance to increase awareness of how resources may be diverted and find out whether this is happening.

- Negotiate increased transparency on the part of military partner countries in exchange for provision of capacity-building assistance, by supporting the development of anti-corruption action plans for the institutions as part of the training received. Follow up on these action plans.

- Increase transparency of capacity-building programmes, especially as regards the allocation and disbursement of training and equipment (see, e.g., TI UK 2015)

- Disseminate lessons learned.

- Unlike most Western countries, Nigeria does not have dedicated Coast Guard that is separate from the Navy. Instead, the Navy carries out both traditional defensive tasks as well as the coast guard duties, which are typically more aligned to policing. The Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) also undertakes some coast guard functions (see section on AFRICOM and capacity building in this paper).

- This type of assistance is typically referred to as “security assistance” or “train-and-equip programmes” in the United States, “defence engagement” in the United Kingdom, and “military aid” in Canada (TI-DS 2017).

- One of the best-known examples is the Afghan Mujahideen, who received arms, training, and funding from the United States in the 1980s, only to later turn into an enemy of that country.

- Experiences from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Nigeria show that corruption arguably has diminished the effectiveness and morale of forces, which in turn has impaired the fight against groups like the Taliban, the Islamic State, and Boko Haram (see, e.g., TI-DS/CISLAC 2017).

- The British Government offers only training to defence agencies in Nigeria. This differs from the more extensive assistance that many other nations provide, which may include training, equipment, and defence services. Both equipment and defence services can include a sales component.

- Obangame Express takes place in the Gulf of Guinea with signatory nations of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct and includes 20 African partners: Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo, Cabo Verde, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Liberia, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Togo. It is similar to Phoenix Express, in the Mediterranean, and Cutlass Express, in East Africa. The “express” exercises are simulations that have been developed in conjunction with all partners. This ensures that they are relevant and meet the needs of the recipient countries. The purpose of the exercises is to objectively assess how the assistance programmes are working and what changes may be required.

- The identity of this country is classified.

- Included were representatives of the Africa Economic Development Policy Initiative (AEDPI),British High Commission, Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC), Delegation of the European Union to Nigeria, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), ECOWAS Security Division, Embassy of Norway, Embassy of the United States, Nigerian Ports Authority, United Nations Development Programme, and the United States Consulate General Lagos.

- Detailed information on programmes and their results (or lack of such) is notoriously hard to come by. According to Hartung (2016), there are well over two dozen US military aid programmes funded and implemented by the Pentagon, but systematic reporting to Congress on these programmes is lacking. Accordingly, it is difficult to accurately determine the recipient countries, type of assistance provided, intended goals of the assistance, and its results, as well as the extent and quality of oversight of the programmes.

- Quantifying piracy is highly problematic, and numbers should be regarded with great caution as they tend to vary considerably depending on who reports and for what purpose (see Steffen 2015). There is a lack of standardised incident reporting and chronic underreporting (some suggest that half of all incidents are never reported due to hassle, costs of delays, and the fear that it will affect insurance costs).

- Past estimates of the annual cost of piracy in the GoG range from $565 million to $2 billion (Osinowo 2015).

- Beginning in 2011, low defence allocations finally increased as a result of the Boko Haram challenge (ICG 2016).

- The Joint Task Force combines Army, Navy, Air Force, and mobile police units.

- For a more exhaustive overview of types of corrupt behaviour, see Transparency International’s typology containing 29 specific types of corruption risk especially relevant to the defence sector (TI-DS 2015).

- See, for example, Transparency International UK, Corruption threats & international missions: Practical guidance for leaders; NATO Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre, Counter- and anti-corruption: Theory and practice from NATO operations; and the United States counterinsurgency doctrine as laid out in Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-24: Counterinsurgency, last updated in 2018. Other useful publications include the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, Building integrity and reducing corruption in defence: A compendium of best practices, which discusses lessons and recommendations from recent military operations. TI UK’s Defence and Security Programme offers a course in collaboration with NATO to senior military officers and officials on how to address corruption in the military and defence sector.