Disappointed by the numerous failures of anti-corruption reforms, international organisations, scholars and policymakers increasingly place their hopes on the inclusion of female representatives in elected assemblies. One of the most consistent findings in contemporary corruption studies is the link between the share of females in elected office and the level of corruption.b5285c28997a372625383950f34c01c994800cac2d955af5 These studies, which involved the analysis of a significant amount of cross-national data, show that the greater the number of females in elected assemblies, the lower the level of corruption. While the causality most likely runs in both directions,9c99867c2a5f there is evidence that female politicians reduce corruption.

Thus far, studies have focused on aggregate indices of corruption, rather than on its vastly different forms. However, research increasingly shows that distinguishing between different forms of corruption helps us to understand the effects of anti-corruption reforms (Bauhr 2017). Distinguishing between different forms of corruption can therefore help us understand why females in elected office reduce corruption.

One of the most important and widely used explanations thus far for why women reduce corruption is the fact that women are on average more risk averse than men. Since corruption is a criminal activity in most contexts, corrupt officials risk being punished by the legal system or the electorate. Women are therefore less likely than men to take the risk of engaging in corrupt actions. This is particularly true in contexts where there is a high risk of exposure and punishment. For politicians, this will be in areas where the electoral accountability is high, first and foremost in consolidated democracies. Studies that support this theory include:

- Women’s representation, accountability and corruption in democracies (2017)

- “Fairer sex” or purity myth? Corruption, gender, and institutional context (2013)

- Gender and corruption (2001)

However, it is important to note that women are a diverse group, and not all women will follow the norm. Elite women that challenge prevailing norms may be less likely to be risk averse than the average woman. Furthermore, in many contexts not being corrupt, or engaging in anti-corruption activities, also entails a high risk.

Women’s risk aversion is also not the only explanation for why increased female representation can reduce corruption. Women also have a different political agenda than men. In particular, females in elected office will reduce corruption, not only because they are less corrupt, but because they are more likely than men to push forward a political agenda that reduces corruption.

Why and how women in elected assemblies curb corruption

Corruption can be defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. This is a complex phenomenon that occurs in many forms, but can generally be categorised into two: Petty corruption and grand corruption. Petty corruption occurs mainly as low-level transactions in exchange for public service delivery. It impedes an efficient and just public service system. Grand corruption, on the other hand, is defined as collusion at the highest level of government. Activities involve procurement and large financial benefits among public and private elites. The general public rarely observe these transactions directly. They are detrimental for equal access to power.

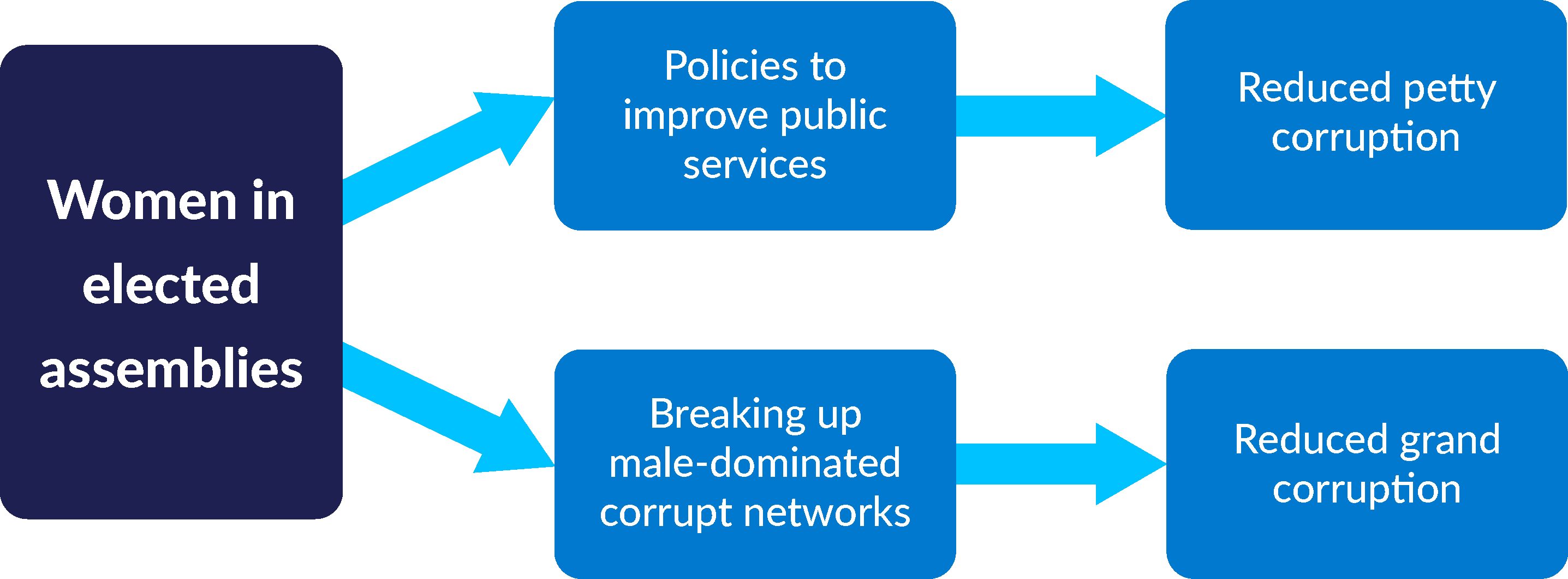

Distinguishing between petty and grand corruption helps understand why female representation reduces corruption. Women in elected office mobilise against both forms of corruption but for partly different reasons. Women who attain public office seek to further two separate political agendas: 1) the improvement of public service delivery; and 2) the breakup of male dominated networks.

Women are on average more dependent on public services. They are therefore expected to work politically to reduce corruption that harms public service delivery. Female politicians will particularly seek to improve the conditions in the services that benefit women, such as healthcare and education. By pushing for effective and encompassing public services, female representatives reduce the need for petty corruption. We call this the women’s interest explanation.

Men mostly dominate the inner circles of power. Hence, women cannot access privileges that come with grand corruption, and they are excluded from important decision-making.It is therefore in the individual interest of female politicians to break the corrupt structures and networks that are detrimental to their political careers. We call this the exclusion explanation. Figure 1 illustrates these mechanisms.

Figure 1: How women’s representation in elected assemblies reduces corruption

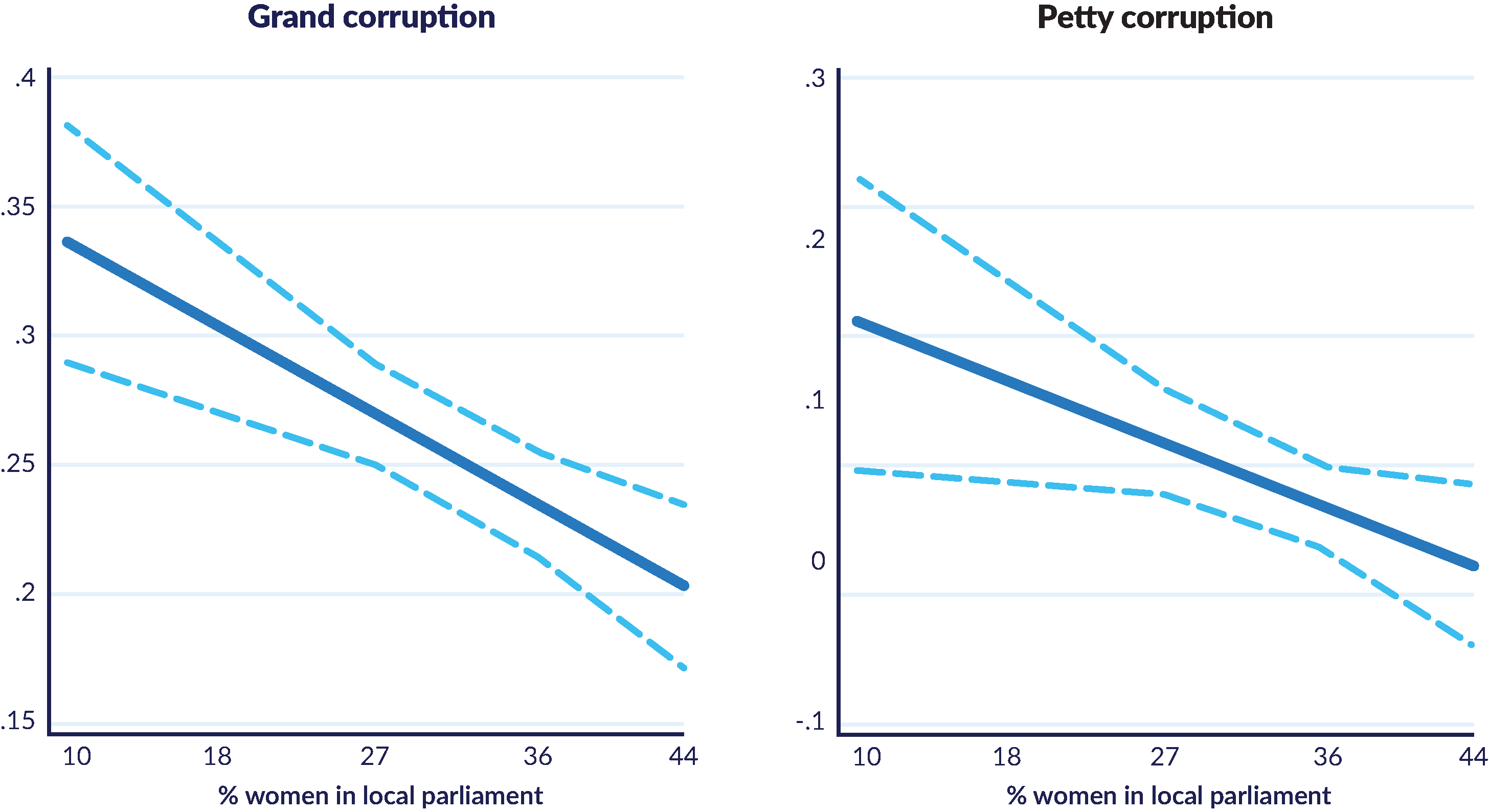

The data confirms that female representation reduces petty and grand corruption

Our study from 20 European Union (EU) countries confirms that the inclusion of women in locally elected assemblies will reduce corruption. We find strong evidence that the proportion of local female political representatives is associated with lower levels of both grand and petty corruption. In particular, Figure 2 shows that as the share of females in locally elected councils increases, the level of both grand and petty corruption decreases. For instance, in the regions where the local council has more than 30% women representatives, less than 10% of the population has experienced petty corruption.

Interestingly, there are differences between the public sectors. Female representation decreases the level of corruption in the health and education sectors. However, it has no effect on bribes paid to law enforcement agencies. This may be because women are on average more likely to be exposed to corruption in education and healthcare than in law enforcement. We also find that while both men and women experience less bribery as the share of women elected increases, the rate of bribe payment by women citizens decreases most strongly. For example, a woman is roughly 3.5 times more likely to pay a bribe in education when the share of female representation is at its lowest compared to when it is at its highest.

Figure 2: Women in local parliament reduces both petty and grand corruption

Support women-backed anti-corruption agendas

There is no doubt that gender equality is a vital part of the human rights agenda. Increasing the inclusion of female representatives in elected assemblies is an important and desirable policy in itself. An important extended effect is reduced corruption in society. Although our study only covered Europe, the other studies cited reveal similar effects across the globe. However, before we promote female representation as a part of an anti-corruption agenda, we should understand the mechanisms behind this expectation, i.e. why women reduce corruption.

Women in elected assemblies are not a homogenous group, and will not necessarily work to curb corruption just because they are women. We need to better understand their role as politicians and how they work to push forward agendas in their own and society’s interest. Often, this agenda includes improving public services and breaking up male-dominated corrupt networks. Donors who work to promote women’s participation in elected assemblies can contribute to the positive effects by supporting the anti-corruption agenda that female politicians choose.

- Dollar, D. et al. 200. Are women really the “fairer” sex? Corruption and women in governmen

- Swamy, A. et al. 2001 Gender and corruption

- Esarey, J., and Chirillo, G. 2013. “Fairer sex” or purity myth? Corruption, gender, and institutional context (PDF)

- Esarey & Schwindt-Bayer 2017. Women’s representation, accountability and corruption in democracies

- Sierra, E. and Boehm, F. 2015. The gendered impact of corruption: Who suffers more – men or women?