Introduction

Indigenous communities play an essential role in successful forest conservation. Forest governance regimes led by Indigenous peoples can be “as effective as (or even more effective than) traditional protected areas in buffering against deforestation and forest degradation” and “formal recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights over their forest lands can also slow deforestation” (Fa et al. 2020).

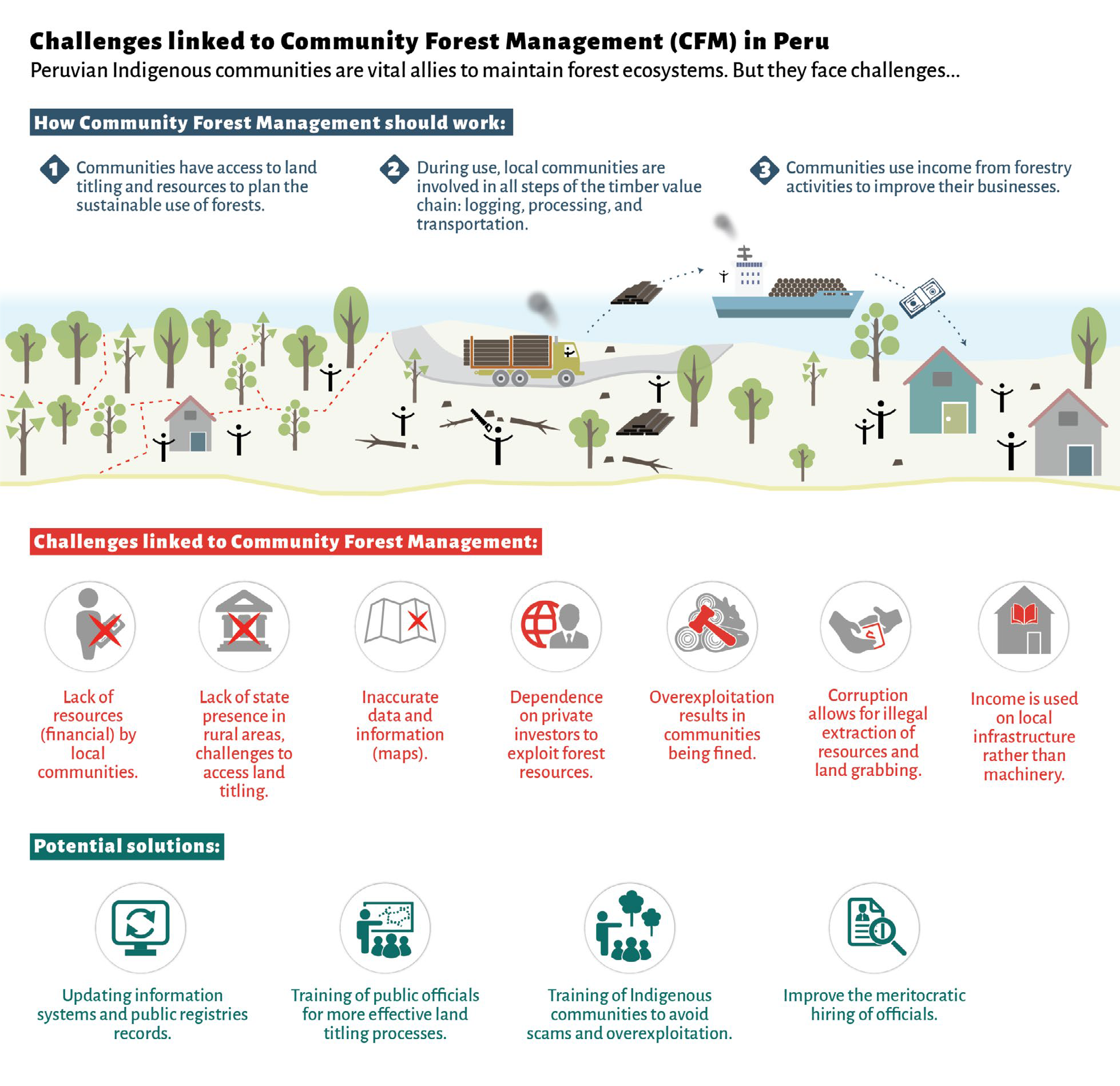

One tool to promote the participation of Indigenous peoples in forest conservation and sustainable management is Community Forest Management (CFM). CFM initiatives recognize that the involvement of Indigenous communities is essential to the preservation of the forest upon which those communities depend. It encourages their participation in forest management by reinforcing communities’ decision-making powers and promoting equitable benefit-sharing. By building capacity at the community level, CFM aims to prevent abuses from third parties and community leaders that could act against the common interest (see Box 1).

Key terms

- According to the International Land Coalition,land grabbing involves the acquisition of land in violation of human rights, without the consent, agreement, or participation of the affected land-users. Commerce of this illegally appropriated land then becomes land trafficking (Shanee and Shanee 2016).

- Community Forest Management is defined in this brief as planned forest activities conducted by local actors, including the development of local businesses (e.g., handicrafts), based on sustainable exploitation of the forest. These initiatives go beyond recognizing Indigenous communities’ ability to manage and protect forests, to also include promoting community participation in decision-making and equitable benefit sharing throughout the timber value chain.

- Given its salience for the forest sector, this brief adopts Robbins (2000, 245) definition of corruption as “the use or overuse of community (state, village, city, etc.) natural resources with the consent of a state agent by those not legally entitled.”

Box 1. About the research

The Peru research component of the Targeting Natural Resource Corruption (TNRC) project aims to improve understanding of the actors and interests involved in the exploitation of timber in the Peruvian Amazon, particularly how corruption takes place, contributes to illegal logging and deforestation, and impacts local communities.

This brief focuses on case studies from two regions, Pasco and Ucayali, where the USAID Peru Bosques and Pro-Bosques projects have been implemented. The research further seeks to facilitate understanding of the complexity of targeting corruption in a single rainforest ecosystem of global importance and to improve understanding of how international projects work in local Peruvian contexts.

The brief triangulates three sources of information:

i) official reports (including deforestation data) and regulations issued by national authorities; ii) reports and articles produced by non-state actors, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), multilateral actors, and academia; and iii) 20 semi-structured key informant interviews with Indigenous leaders, current and former public officials, journalists, and NGO staff. In addition, early results were discussed at a workshop with civil society groups in Ucayali in November 2021.

International actors, including USAID, have prioritized CFM in Peru for more than 30 years. For instance, support has been provided to the government’s commitments for long-term forest management (Cossío et al. 2014). CFM, including activities mainly targeting Indigenous communities, is a core part of USAID’s forest conservation initiatives in Peru (see Box 2).

Box 2. Examples of USAID support to Indigenous CFM in Peru

One of the oldest CFM projects involving timber management by Indigenous communities in Peru was Yanesha Forestry Cooperative (COFYAL) in the Palcazu Valley, Pasco, in the 1980s. USAID supported the forest management component of the project that was designed by the Centro Cientifico Tropical de Costa Rica (Cossio et al. 2014).

Currently, USAID partners with Mirova Natural Capital and the NGO AIDER to support the Forest Alliance, which promotes the conservation of Amazon forests through CFM and the strengthening of inclusive sustainable businesses. The project works with 350 families of the Shipibo Conibo and Cacataibo Indigenous Peoples in Ucayali.

Besides this direct support to CFM, USAID’s Pro Bosques programme is currently working with key governmental forest institutions, such as OSINFOR (the Peruvian Forests and Wildlife Resources Control Agency), to strengthen the capacity of local communities, including Indigenous communities, to participate in CFM projects.

While CFM has led to many positive results, concerns remain about the feasibility and sustainability of some CFM projects led by Indigenous communities (Proyecto USAID Pro-Bosques 2021; Proyecto Cambio Climático 2018). Indigenous communities have become one of the leading timber suppliers in the Peruvian market, with 25.4 percent of Indigenous communities implementing traditional forest management practices. However, only 10.4 percent of Amazonian Indigenous communities report developing timber harvesting activities (Proyecto USAID Pro-Bosques 2021). Instead, communities mainly provide only the needed physical territory; most forests are managed, and almost all forests harvested and timber transported and processed, by others. As well, third- party use of Indigenous community forests without a contract with communities is unfortunately still a common practice, with severe consequences (see Box 3).

Box 3. Peru’s timber value chain

In Peru, the timber value chain involves various steps:

- Management of natural forests or plantations where the resources is extracted;

- Transportation of the wood to the primary transformation centers (for sawing, squaring, re-sawing, chipping, laminating, etc.), although some of the processes (like sawing) can also be carried out in the forest;

- Transportation of the processed timber to the internal or external market, or to second transformation industries that further processes and adds value to the timber;

- Transport to the local market or export.

Indigenous communities are mainly involved in the first stage (Proyecto USAID Pro-Bosques 2021).

A variety of obstacles inhibit Indigenous communities’ involvement in CFM-based legal timber harvesting, such as a lack of technical and financial support, bureaucratic barriers, and lack of capacity. The role of corruption, however, is less understood, despite solid evidence of forestry corruption globally (Tacconi and Williams 2020) and in Peru (Center for International Environmental Law 2019; Urrunaga, Johnson, and Orbegozo Sánchez 2018). Forests are spaces of struggles between different actors, including communities and forest bureaucracies (national, regional and local authorities), with these struggles impacting corruption and CFM outcomes (Bille Larsen 2015). Yet we tend to ask neither how these communities perceive the role of national and regional authorities in corrupt practices or how forest-related corruption is a barrier to Indigenous communities’ participation in CFM. This Brief aims to help fill these knowledge gaps, generating recommendations to strengthen initiatives that promote the participation of Indigenous communities in forest conservation and sustainable management.

Indigenous peoples and their importance for forest conservation in the Peruvian Amazon

Peru contains 11 percent of the Amazon rainforest, and within this area, Indigenous community territory represents 33.4 percent. The level of recognition afforded to this territory varies considerably, however, as seen in Table 1. This contributes to the “huge contradiction” recognized by one interview.7edf9fb0820e And while poverty affects 17.6 percent of people with Spanish as mother tongue, this reaches 50 percent among those with an Amazonian indigenous language as mother tongue (Ministerio de Salud, 2021).

“Indigenous peoples have tenure of approximately 15 and 20 million hectares...some with property titles, others with possession titles. And yet their families live in poverty, with the vast majority of them living in conditions of extreme poverty. How is it possible that, with this wealth of 20 million hectares, these families live as they do? That’s a terrible thing, a huge contradiction, right?” (Interview with public servant – Lima, June 14, 2021).

Peruvian law defines Indigenous235140a6ce5a communities as those communities that “have their origin in tribal groups of the Amazon and are constituted by groups of families related by language or dialect, social and cultural characters, common and permanent tenure and usufruct rights of a common territory” (Cossío et al. 2014, 6). The Peruvian Constitution of 1993 recognizes ethnic and cultural identity as a fundamental right, and forests are recognized as part of the cultural identity of Indigenous communities. The 1993 Constitution, however, also stipulates that the state has authority over all natural resources, including forest resources and services, regardless of whether they are in the public or private domain. Indigenous communities have therefore regarded the 1993 Constitution as a step backward regarding the rights to their territories, as explained in Box 4.

Box 4. A history of struggles for legal recognition

The constitution adopted in 1993 became a milestone in the long struggles between the state and Indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon that “have suffered the relentless practice of the invasion of their lands and incessant deforestation of their forests.” (Rios Cáceres, Tuesta, and Smith 2019). Since the 1920s, Peruvian constitutional law had adopted several steps towards recognizing Indigenous communities’ lands. The Indigenous Communities Law of 1974 recognized for the first time the right of Amazonian Indigenous peoples in Peru to the collective property of their territories. This recognition, however, was limited to the lands around settlements. The 1977 Forestry and Wildlife Law prohibited the titling of lands within indigenous communities to benefit non-indigenous. This law was a milestone in the relationship between the state and indigenous communities because the state recognized the communities as legal persons. The 1979 Constitution recognized the inalienable, non-seizable, and imprescriptible nature of communal land, but this was abolished by the 1993 Constitution, undermining the legal security of indigenous people to their land (Pinto 2009; Manríquez Roque 2017).

At the same time, Indigenous peoples have taken actions to defend their territory and their fundamental rights. They have acquired spaces in both national and international arenas, assumed ownership of national and international legal tools (such as ILO Convention 169), and have started to produce “their own standards and norms, resulting in the need to come up with a plan for territorial management from an indigenous perspective” (Ríos Cáceres, Tuesta, and Smith 2019).

It is within this context that CFM initiatives emerged in Peru (see Box 5). Sustainable timber extraction can be an important income source for communities living under the poverty line and with poor access to public services (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática 2018b), although sustainable timber extraction is not the only activity promoted by CFM, and one of CFM’s key characteristics is diversification (e.g., development of activities such as handcrafts). At the same time, however, the model is set within the national legal framework. This framework grants user rights only to titled Indigenous Amazonian communities and allows third parties to obtain forest concessions within the Indigenous territory.

Finally, although protected areas and Indigenous territories in Peru suffer relatively less deforestation than non-protected areas (GIZ Programa Global “Política de Tierras Responsable” Perú 2017), deforestation within Indigenous communities does occur (Finer, Mamani, and Silman 2021; Sarmiento Barletti, Begert, and Guerra Loza 2021). In Ucayali, over the last 20 years, Indigenous communities have lost 100,085.15 hectares of forest, with 2019 and 2020 seeing exceptionally high forest losses. In some cases (e.g., Community of Fatima, Ucayali), there is evidence of a certain level of community involvement in illegal logging. However, land grabbing involving outsiders is a significant driver of deforestation in Indigenous communities (e.g., Community of Sinchi Roca, Ucayali or El Sira Communal Reserve, located in the regions of Pasco, Huánuco, and Ucayali).

Table 1. Indigenous territories by category and level of recognition (Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georeferenciada 2020)

| Level of recognition | Peru | Amazon |

| Officially recognized | 23.4% | 22.1% |

| Not officially recognized | 2.6% | 0.5% |

| Indigenous reserves or intangible zones (reserved for Indigenous peoples in isolation) | 3.0% | 0.5% |

| Proposed Indigenous reserves | 4.4% | 0.5% |

| Total | 33.4% | 28% |

The domino effects of insecure land tenure: Forest encroachment and land grabbing

Programs to promote forest conservation and the sustainable exploitation of the Amazon rainforest require communities to present their land titles with updated boundaries and documents proving that they have been registered and recognized by the authorities. Indigenous communities, however, have seen these requirements as administrative barriers rooted in the lack of recognition of Indigenous communities and their ownership of historical territory. Public servants prioritize national administrative regulations over the needs of the Indigenous population. These administrative requirements force Indigenous peoples in the Amazon to engage in lengthy and expensive processes involving obligatory administrative, financial, and legal demands to be able to protect their territory, livelihoods and to access public services. These administrative requirements are a significant point of contention between Indigenous peoples and many national-level and regional authorities.

First, land titling of Indigenous territory has historically been neglected by the authorities, with only small budgets allocated to community land titling processes. Peru’s Ombudsman office has shown, for example, that even if there have been some positive developments to adapt the regulations to the needs of Indigenous people, there is a lack of political commitment at national and regional levels to address the barriers reported by the Ombudsman in various reports. As the Ombudsman office describes, “the recognition of indigenous communities and the titling of their lands are regulated by pre-constitutional norms…which complicate the recognition and real exercise of the property rights of the communities; and contribute to public officials applying them inappropriately” (Defensoría del Pueblo 2017).Therefore, there is a need for legal reforms to eliminate administrative barriers.

Budgetary restrictions in regional governments also limit the retention of skilled personnel in relevant administrative positions. As explained in the interviews below, Indigenous leaders perceive these problems and delays in land titling at the regional government level as highly selective and directed towards Indigenous and communal lands, with the intention of undermining their constitutional rights in favour of third parties.

“There are communities that have spent 10, 15, 20 years waiting for their recognition or their land titling, and during this time, well, the regional governments obviously give land titles for individual properties, right? So, as I told you, one of the main deficiencies that we can notice regarding the role that regional governments play in land titling (and a very important one) is the lack of prioritization of the institutional budget. Much of the budget used to obtain land titles goes to individual properties and not to Indigenous communities” (Interview with public servant – Lima, June 22, 2021).

“So it is easier (well, I don’t know if it is easier, but this is what I see) for them to grab a property, a land title, and give it to an individual person rather than to a community. We have fought for years with my community for the issue of expansion [of community lands], years indeed. Since I was born, my parents have already lived in this place...And do you know what happened? After many years, they have always denied it...there was no budget, there was no budget, the State does not have the money for this...But when a small landowner, two or three, went to request the area, they give the land title at once. I mean, I don’t know what the magic is, right? They give them the land title at once without going, without doing field work, without doing anything and, what’s more, the gentlemen [public servants from the regional office in charge of land titling] don’t even know the territory, they don’t know, they don’t even know where it is” (Interview with Indigenous leader – Pasco, March 11, 2021).

Interviews commonly described this neglect and/ or favoritism as “corruption” that undermines initiatives designed, in principle, to ensure legal titles for communal lands. Indeed, land titling projects carried out over the past ten years have only achieved limited success in securing Indigenous peoples’ land. Between 2010 and 2020, only 147 out of 719 Indigenous communities were titled as part of 14 projects with that goal (Huamani Mujica 2021). Moreover, some implementers of these initiatives have prioritized non- contentious cases over more difficult ones, neglecting communities that have been urging the formalization of titles to protect their territory and livelihoods (see Box 6).

Box 6. The case of Santa Clara de Uchunya

Emblematic land grabbing cases have fed distrust of regional and local authorities involved in land titling processes. One such case is the Santa Clara de Uchunya Indigenous Community located in Requena district, Coronel Portillo region, Ucayali.

The community reported land grabbing and deforestation in their ancestral territory by a palm oil company. Between 2008 and 2009, the Directorate of Agriculture (DRA) of the Regional Government granted 212 “certificates of possession” to individual owners (parceleros) on the ancestral territory of the community. The parceleros later requested the granting of ownership of these properties superimposed on the land claimed by the community and registered the titles in the public registry. They thus became considered “formal owners.” The community did not have the opportunity to object to the certificates or titles, given that they were not aware of them. Subsequently, the new landowners sold the properties to the company Plantaciones de Pucallpa S.A.C., owned by Grupo Melka, and known today as Ocho Sur P.S.A.C. The company acquired approximately 6,845 hectares of the community’s ancestral territory.

Between 2014 and 2015, the DRA granted at least 82 new “certificates of possessions” in the territory claimed by the community, but this time the community managed to challenge the process. In 2016, the DRA declared the ex officio “records” nullified after detecting irregularities.

The community has been the target of threats and attacks for defending their territory and preventing the expansion of oil palm plantations (and therefore deforestation). Due to the lack of action by Peruvian authorities, the community brought their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), and in 2020 this body issued Resolution 81/2020, granting precautionary protection measures in favor of members of the Santa Clara de Uchunya Indigenous Community.

For more information, see: the 2018 Report in Mongabay and the 2020 OAS Decision.

The poor performance of community land titling efforts contrasts with individual land titling promoted by the national government in alliance with regional and local authorities. Some programs, such as the Comprehensive and Sustainable Alternative Development Program (PIRDAIS), have included land titling among its support for farmers to replace illicit crops like coca with legal crops. However, in some cases, individual land titles overlap with territory claimed by Indigenous communities (GIZ Programa Global “Política de Tierras Responsable” Perú 2018). Delays faced by Indigenous communities in their land titling processes have made them vulnerable to losing land rights in the face of individual titling processes.

Second, the outdated and inaccurate land register at the National Superintendency of Public Registries (SUNARP) has also contributed to conflicts over land. For example, in 2017 SUNARP Ucayali reported that 247 out of 276 maps of Indigenous communities lacked geographic coordinates (Laguna Torres 2020). Furthermore, national regulations give the older public registries in SUNARP priority, so that local and regional authorities “adapt” their own land registry information to SUNARP’s to avoid rejection of submitted land titles—even if they know this is inaccurate and creates problems between communities (Interview with NGO - Amazonas, July 7, 2021). These inaccuracies could be resolved with a new land registry based on georeferenced maps. However, although some private institutions have shown it is possible to produce this type of map in Peru, this has not to date been introduced by the government.

A third main feature in land ownership disputes comes from infrastructure developments related to agriculture promotion in the Amazon. While recognizing the need to transport agricultural products and improve the communication system, for some communities, the opening of new roads within their territory has increased the risk of deforestation and land grabbing (Comunidad Nativa de Alto Tamaya- Saweto et al. 2020). The Alternative Development Program has, for example, supported the maintenance of rural paths to reduce the transport costs of products and make legal crops more attractive to grow (Comisión Nacional Para el Desarrollo y Vida Sin Droga 2019). However, Indigenous communities have reported the construction of roads within their territory without a process of prior consultation.

In addition to the potential social and environmental costs of the roads, research has also shown potential negative economic impacts as well as corruption risks involving national and regional governments (Vilela et al. 2020). The construction of the Inter-Oceanic Highway (or IIRSA south) is recognized as one of the major corruption cases involving Brazilian firm Odebrecht, former national and regional Peruvian government officials, and Peruvian construction firms (IDL Reporteros 2019). The corruption raised serious doubts as to the validity of the environmental impact assessments used to authorize the road, and there have also been concerns that the road has contributed to deforestation in Madre de Dios (Sierra Praeli 2018; MAAProject 2016). Most recently, the Comptroller General of the Republic of Peru found Ucayali authorities responsible for favoring a company in the public bid to construct the Neshuya-Curimaná road.

Finally, Indigenous communities attempting to gain legal tenure via regional governments also face encroachment from forest concessions. Some authorities have used “conflicts” between Indigenous communities and those with forest concessions to deny, or delay until the end of a forest concession, the recognition of land ownership on the part of Indigenous communities (Servindi 2018). Regional authorities from the Agrarian Directorates have reportedly also allowed irregular changes in land use, thus opening up forests for destruction (PROETICA 2018).

The absence of the state and inactive monitoring

For community territories to be properly mapped, an updated registry of communities is the first requirement. Some regions in Peru lack even this basic information, indicating a level of historic neglect from regional authorities towards Indigenous communities.

One interviewee noted that:

“When I arrived here [in 2020 to Ucayali], precisely in this Management Office [Management Office of Indigenous Affairs], and I asked the manager, I said: ‘Hmm, do you know how many communities we have?’

‘Well,’ he tells me, ‘About 450.’

‘Have you identified them somewhere? A map, in which areas, which territory...’

‘No, we do not have this information.’

But then, how are they going to work...that is, how am I going to work with the communities, or how am I going to work with their representatives, if they are not known, right?” (Interview with public servant – Ucayali, June 25, 2021).

In this context, it is unsurprising that authorities such as the Attorney General’s Office or the police have insufficient budgets to access many rural communities to address complaints of illegal logging. These resource constraints mean it is impossible to hire adequate personnel, offer competitive salaries, and guarantee supplies (including fuel), which undermines the efficacy of criminal code reforms on prosecuting environmental crimes, including illegal logging. One interviewee reported that:

“[t]he state does not have monitoring capacity. I mean, it never had. And this with regard to all issues, right? Regarding the forestry issue, the mining issue, the oil issue, the invasion of settlers, land trafficking, right? You don’t have that ability. And they always say ‘there is no budget, there is no staff,’ for all their lives.” (Interview with NGO – Amazonas, July 7, 2021).

The territorial reach of the Peruvian state has been characterized as profoundly uneven and unequal (Dargent and Urteaga 2016). The state has a weak penetration capacity across many areas, and, in some cases, local powerholders prevent state authority from being exercised. Indigenous communities perceive this absence or weak presence of state agents in certain regions, including health centers, schools, and police and forest authorities, as “indifference from the authorities who do not intervene even in situations of “flagrante delicto” (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática 2018a). Indigenous leaders interviewed considered this indifference a form of “corruption.”

Besides the absence of the state, interviewees also identified an “active inaction” by authorities, linked to corruption. This inaction allows the transport of timber without effective controls. For example, a widely known system allows transportation of timber, using the main roads and rivers, from the forest to transformation centers. One interviewee described this:

“If you go to Codo de Pozuzo…starting at 6 p.m., tremendous trucks are emerging...I don’t know what these big machines that produce timber are called…they are leaving Santa Marta, to come to this area, right? You see trucks full of timber. Why? So that the authorities do not realize it, at this time the timber is already extracted from the forest. Yes it is easy. And without control, there is no control” (Interview with Indigenous leader – Ucayali, March 24, 2021).

This active inaction is expressed as a lack of innovation in tracing timber. Authorities undoubtedly face major challenges overseeing the vast Amazon territory. Yet there are solutions that could be implemented to improve oversight of forests and address illegal logging (Grant, Freitas, and Wilson 2021). For example, the Madre de Dios regional government ordered in 2021 the mandatory use of an app for electronic transportation guides. Such apps are meant to help trace and control timber, but the tool has not been adopted in all regions. In addition, authorities could strengthen and increase the number of inspections and controls at timber transformation centers (e.g., sawmills), which are often located in relatively easy-to-reach urban areas. Implementing this type of measure would require political commitment at the national and regional level, however, as one interview with a journalist described:

“But when I was talking to current and former OSINFOR officials, they told me that perhaps what should be done is not so much to go to the field, but to find a middle ground, which in this case would be the sawmills, returning to the issue of wood, no? Because this is where the first transformation of the timber takes place and where one could corroborate if something illegal is going on in the forest and start connecting a little the dots...This is more political, because in reality the authorizations to transport the timber in the sawmill are usually given in these Forest Directorates.” (Interview with journalist - Lima, March 16, 2021).

Insecure land tenure, state absence, poor enforcement, and monitoring inactivity are therefore interlinked factors that combine to, as the next sections show, facilitate timber crimes, undermine the potential impacts of CFM initiatives, and expose local communities to violence.

The effects of insecure land tenure and weak state presence on CFM

CFM faces a range of challenges before it can become a main source of income for Indigenous communities (Proyecto USAID Pro-Bosques 2021; Cossío et al. 2014; Bille Larsen 2015). One explanation is that, given the extremely limited public services in Indigenous areas, income generated from legal CFM timber sales must be immediately reinvested in basic health and education infrastructure. This limits the possibility of reinvesting resources in forest management or the recovery of the forest (Proyecto USAID Pro-Bosques 2021). Additionally, local businesses promoted by CFM initiatives, such as handicraft makers, face challenges in obtaining raw materials like huayruro seeds, mahogany, and cedar. This material was historically extracted from standing trees in the forests surrounding communities (Interview with Indigenous leader - March 2, 2021). But illegal logging of protected species has resulted in their absence from local forests. In many Amazonian communities, women must now buy these raw materials, increasing the production costs of their handcrafts.

The lack of state programs and public centers aimed at training Indigenous peoples to improve forest management in their territories presents another challenge. OSINFOR and some NGOs (such as Rainforest Foundation US) have developed initiatives to provide technical support and equipment to Indigenous and local communities to oversee the forest under their control. But without the resources to respond to the reports of illegal logging or land grabbing, and to protect the communities, the effectiveness of these initiatives is weakened. One example is the case of the community of Saposoa (Ucayali), which has worked with different partners to develop CFM and to incorporate technology to detect and report illegal logging within their territory. These days, however, the community is surrounded by coca fields. The impunity enjoyed by drug traffickers in the area has created new risks for the community and for the positive developments they have achieved.

Interviewees stressed that the lack of state control at timber extraction points, along with limited technical and legal public resources to support Indigenous communities when negotiating agreements, has contributed to forest scams that take advantage of Indigenous communities. In addition to bad deals and violations of forest management plans by third parties, the prevalence of corruption in the timber value chain allows timber laundering through legal forest concessions and Indigenous territories that can result in fines and other penalties for Indigenous communities. For example, when authorities detect species that are not approved in the Forest Management Plan paperwork, or when declared timber comes from areas where there is no evidence of logging, Indigenous communities are fined. In 2021, fines incurred by Indigenous communities due to the overuse of forest concessions or the extraction of protected species amounted to around USD 12.5 million. This is an amount that Indigenous communities cannot afford to repay (Comisión Especial de Cambio Climático del Congreso de la República, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, and Programa Regional Seguridad Energética y Cambio Climático en América Latina 2021). When a community does not pay, public authorities can seize the community’s bank account, blocking it from benefiting from state programs such as payments for ecosystem services.

CFM initiatives aim to prevent scams targeting Indigenous communities, as well as the abuses of some Indigenous leaders against the communal interest. However, the complexity of the CFM model means Indigenous communities keen to engage with it are highly dependent on external actors, some of whom betray their trust. Current regulations act as a barrier to entry, forcing communities to depend on third party investors, which in turn exposes them to abuses.

Box5. Challenges linked to Community Forest Management (CFM) in Peruvian Amazon

Credit: Source: Camila Gianella and Levi Westerveld

The links between tenure, killings, illegality, and corruption

Efforts to develop CFM often take place in areas where communities are suffering from threats of violence and loss of their territory. Such a situation challenges CFM efforts in the Peruvian Amazon. Struggles over territory in a situation of insecure land tenure result in death threats and killings. Indigenous leaders defending their communal territory (e.g., Apu Arbildo Meléndez and Mario Marcos López Huanca) have been killed in recent years, with others receiving death threats or being forced to abandon their communities.

From the perspective of Indigenous leaders interviewed, this violence is a consequence of corruption in regional governments and the activities of criminal organizations involved in land grabbing, illegal logging, illegal gold mining, and illicit agriculture (e.g., coca leaf production for cocaine). Several interviewees considered these activities linked. First, the Indigenous territories are targeted, land titles are obtained from local or regional authorities, and a struggle for the territory emerges. Indigenous people may be expelled with violence, or, when they resist, their leaders killed. The area is then logged, and mining or agriculture begins.

“Through the Regional Government 28 people were given titles of territory within the community, territory which already had been recognized but did not have a land title. So when he reported this, that’s when Arbildo dies, well, Arbildo was on the list…for defending his land Unipacuyacu” (Interview with Indigenous leader – Pasco, March 11, 2021).

“The independent possessors, who we have called settlers for years, are recognized within three months, often with land titles, by making a request to the Ministry of Agriculture. However, the indigenous communities have to spend 20, 30 years in the case of Unipacuyacu, 30 years! In the search of their land titles, many leaders have died for defending their territory. Lately the Apu Arbildo was brutally murdered. And, have the State or the Regional Agrarian Directorate [in this case Huánuco] taken action on the matter? No. This situation is simply going to remain in impunity” (Interview with Indigenous leader – Ucayali March 24, 2021).

The modus operandi described in the above case from Unipacuyacu (a community located between Huánuco and Ucayali) has been reported in other cases too (e.g., in the case of Santa Clara de Uchunya). The common element in these cases is that regional authorities provide individual land titles or possession certificates to individuals from outside the community.

The Peruvian Congress has, unfortunately, rejected ratification of the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (Escazú Agreement). This agreement aims to strengthen the transparency of environmental decision-making processes and provide remedies and redress to victims of environmental harm. The agreement also contains specific provisions for human rights defenders, which includes environmental defenders.

Despite this failure, in a context of continuous attacks against Amazonian Indigenous leaders, in 2021 the government decreed a new regulation to protect environmental defenders. However, no additional budget was allocated for it. Rather, it was expected that the already underfunded police, or ministries, would invest scarce resources to protect Indigenous leaders under threat.

Nevertheless, Indigenous peoples continue to protect their territories and natural resources due to “deep spiritual and cultural ties to their land and (…) local ecosystems reflect[ing] millennia of their stewardship” (Garnett et al. 2018). One Indigenous interviewee noted that:

“[t]his year…we make a one-hectare farm. For what? To plant our yucca, our banana, our sweet potato...that is, everything we will need, right? In other words, to be able to eat, to be able to subsist, right? And we have also identified our fishing areas, that is, our streams, our rivers; we have identified our hunting areas, that we should not touch...that is, make a small farm there. Why? Because the animals will be there. Then we go hunting in order to eat. So, every year, every year, always a community member makes use of a block, every year a block. Sometimes some use half blocks...what is the maximum? Two blocks…. While the brother settler, do you know what they do? They, in order to make big farms…they have possession titles, this is it, so the first thing they do is: they come, they make a farm of 20 blocks and they brush it like this, sweeping…20 blocks! For what? To plant grass, to plant coca, just for that, right? So, while we have cared for sooooo many years, so many years we have lived with our territory, and come on, overnight…someone who invades our plots and destroys it ... In that sense we feel abandoned.” (Interview with Indigenous leader – Pasco, March 11, 2021).

Conclusions and policy suggestions

Corruption is a major challenge for Amazonian Indigenous communities as well as for the conservation of the Amazon rainforest. Local and regional authorities often provide, without clear grounds, titles or possession certificates to outsiders, which allows the overuse or even destruction of Indigenous community forests by third parties. Forest authorities, police, and public prosecutors regularly cite resource limitations in explaining delays in responding to reports of illegal logging. However, the underfunding of key institutions appears, at least to those communities most affected by it, like strategic neglect and could indicate corruption. The national and subnational levels of government responsible appear to keep relevant institutions in a situation where they cannot enforce the law. These weaknesses occur in a context where regional politicians have been indicted and prosecuted for corruption. Ucayali’s governor between 2007 and 2014 and Pasco’s governor between 2011 and 2014 have both been prosecuted and sentenced for corruption. More recently, in December 2021, Ucayali’s governor and his general manager were detained on corruption charges, with a court ordering that they should serve 36 months of preventive imprisonment.

The testimonies collected as part of this research show the disruptive effects of insecure land titling on Indigenous communities’ participation in CFM initiatives, but also on the integrity of their livelihoods and practices. While recognizing the structural failings described above, there are a number of positive steps that projects promoting Indigenous peoples’ participation in CFM could implement to address corruption and mitigate its negative effects. Many of these recommendations are well known and not new, but the fact that they have not been fully implemented means there is merit in restating them.

- Programs targeting forest conservation and sustainable management in the Amazon could invest or promote public investment in economic and social infrastructure (such as schools, community buildings, health posts). This should be done in coordination with communities (i.e., communities should prioritize it) as well as with regional and local authorities. As mentioned above, income generated from legal CFM timber sales is often immediately reinvested in basic health and education infrastructure. Having communities invest their own earnings in building public services that other citizens get for free is discriminatory. The state has a basic responsibility to provide public services to the population.

- Indigenous communities need better and more information and training to engage with CFM initiatives. Training should include, in addition to forest management practices, content on how to deal with contracting third parties, technicians, and service providers, as well as how to monitor the implementation of management practices so they do not violate the terms of harvesting authorizations. Administrative procedures to obtain permits to legally exploit forests could also be reviewed, however, adopting an intercultural approach. The current regulatory processes required to develop CFMs could also be adapted to the reality of Indigenous communities living in rural and isolated areas.

- National and subnational authorities should prioritize budgets for forest authorities (E.g., National Forestry and Wildlife Service, SERFOR), including FEMA (the prosecutor’s office for environmental crimes) and the police, in rural and isolated areas.

- The bodies in charge of prosecuting environmental crimes need independence and autonomy. National and local formal and informal networks can weaken the capacity of control bodies, especially for agencies like SERFOR that are decentralized and therefore susceptible to capture by local interest and vulnerable to underfinancing. Reforms, such as the Decree N° 003-2022-MINAM that expands SERFOR’s role in investigating and reporting environmental crimes, should consider measures to strengthen SERFOR’s autonomy.

- As other actors have stressed (Proyecto Cambio Climático 2020), CFM viability depends on the different levels of the government (national, regional and local) protecting the land rights of communities. One first step should be to secure legal tenure by prioritizing community land titling over individual land titling. This is merited because Peruvian law requires that the State establish a special transectorial regime to protect Indigenous peoples and guarantee their rights.

- The capacity of local public servants should be strengthened, especially for those officials involved in land titling and authorizing economic activities and/or changes in land use. This could mitigate the negative effects of the regular rotation of public officials due to budgetary constraints described above. These trainings could be coordinated with the National Civil Service Authority (SERVIR) and provide certification to officials interested in continuing in the public sector.

- To reduce the risk of corruption, the hiring process of national, as well as regional and local, forest authorities could be coordinated with SERVIR, who can develop professional profiles and oversee the selection process to guarantee selections are based on merit.

- SUNARP records should be updated with georeferenced maps. Access to these records and maps should be granted to all regions and authorities to take actions with the same information. There are private initiatives showing this is possible in Peru. Currently, some legislation suggests the promotion of georeferenced maps, but this should be a standard goal and the state should have a timeline to implement georeferenced maps.

- OSINFOR needs more resources, so that it can strengthen and increase the number of inspections and controls at timber transformation centers, such as sawmills.

- As in the case of programs fighting illegal crops, economic alternatives for communities (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) engaged in illegal logging should be provided. Creating protection categories for species (e.g., huayruro) needed by Indigenous communities to preserve their practices, and to generate income, could also be useful measures.

- Officials should create open spaces for intercultural dialogue on forest management to allow communities to discuss their organizational needs, but also their recommendations for how to organize forest concessions. Indigenous peoples could also recommend species to be included in official lists of endangered species.

- All interviews were conducted in Spanish and have been translated to English.

- In this document, we refer to Indigenous communities as those communities living in the Amazon for thousands of years before the Hispanic colonization. Some texts and legal documents also refer to them as “native” communities.