Query

Please provide an overview of the available evidence on how corruption risks in aid programmes are costed and whether any practical guidelines exist for typical or appropriate levels of allocation, or even earmarking, for anti-corruption activities in aid programmes.

Background

The effectiveness of aid can be significantly hampered through corruption (Collins 2020). Further, specific forms of corruption can disrupt the intended beneficiaries from receiving the support that a particular aid investment is supposed to deliver (Collins 2020). For instance, in systems dominated by patronage, “aid money only goes to help certain people who support the government, and those who do not support the government do not get any help” (Collins 2020).

Leaking aid also fuels national corruption challenges. For instance, a huge influx of US assistance to Afghanistan in a context of “poor oversight… had created a situation of endemic corruption” (Dyer 2016).

Aid being lost to corruption not only undermines the intended project impact, but political scandals surrounding aid embezzlement go on to “weaken the support of donor countries’ national electorates”, especially in an international context that is becoming increasingly isolationist (Dávid-Barrett et al. 2020:482).

There are several corrupt ways is which aid money can be misappropriated, i.e., elite capture, embezzlement, bribery, procurement fraud, etc. (Collins 2020; Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers 2020:1). Recent examples of aid being misused include emergency aid during the Covid-19 pandemic with funds being sent to a wide range of countries (Transparency International 2020).

Afghanistan, for instance, received emergency assistance at the start of the pandemic totalling €117 million (US$131 million) from the European Union, along with US$100.4 million from the World Bank and US$40 million from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) (Salahuddin 2020). Soon there were reports of mismanagement and embezzlement of these funds by government officials resulting in “delayed salary payments to doctors, shortages of protective gear for the medical staff treating coronavirus patients, and a lack of oxygen, sanitizers and masks at hospitals” (Salahuddin 2020). The then Afghan government was accused by Integrity Watch Afghanistan (IWA) of “monopolising” donor funds (Salahuddin 2020).

In general, some amount of foreign aid is often known to be lost to corruption, but it is hard to find accurate estimates. This is largely due to corruption and its consequences being inherently difficult to measure (Wathne and Stephenson 2021:4). A World Bank report (2020) looking at elite capture of foreign aid by studying offshore bank accounts found that “the implied leakage rate is around 7.5 per cent at the sample mean and tends to increase with the ratio of aid to GDP” (Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers 2020:4). These “modest” leakage rates represent a lower figure in the sense that they only include aid diverted to foreign accounts and not money spent on real estate, luxury goods, etc. Through combining quarterly information on aid disbursements from the World Bank (WB) and foreign deposits from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the study focused on learning whether aid disbursements trigger money flows to foreign bank accounts (Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers 2020:1). There are a few indicators that could be used to understand the extent of aid being lost to corruption (Kenny 2017):

- Investigative cases of particular aid projects: for instance, the World Bank’s Sanctions Evaluation and Suspension Office tracks investigations that have uncovered instances of fraud and corruption. A scan of cases between 2007 and 2012 “found sanctionable fraud or corruption in 157 contracts worth [US]$245 million” (Kenny 2017).

- Survey evidence about bribe payments: since investigative cases only reveal instances where corruption was discovered/reported, they only present a partial picture. Another method that can be used is survey data. The World Bank Enterprise survey, for example, asks respondents (firm managers from various industry sectors) what was the amount that was spent on “gifts” that were expected in return for winning government contracts (Kenny 2017; World Bank n.d.).

- Estimating the general state of corruption in a given context: often in contexts plagued with high levels of corruption, a portion of donor funds can be lost to corrupt activities. Thus, corruption indicators and political-economy analysis of given contexts could be used in assessing the potential risk of aid being misappropriated (Kenny 2017).

Another way of looking at aid being lost to corruption is turning to outcomes. The idea is that “if the aid program manages to buy all of the things it is meant to buy and deliver them where they are meant to go at a reasonable price, [then] the aid funds [could not] have been lost to corruption” (Kenny 2017). However, using the degree of success or failure of a project as being a proxy for aid being lost to corruption ought to be exercised with caution as issues such as incompetence, mismanagement or contextual factors could affect the final development outcomes.

Donor responses to dealing with these leakages have been in seeking better control over their spending on the one hand while attempting to build recipient government capacity on the other (Dávid-Barrett et al. 2020:482).

Internally, donor agencies “have built upon and strengthened their existing institutions of inspection, auditing, and policy dialogue with recipient countries” (Quibria 2017:8). Multilaterals have even set up specific offices for integrity, for instance, the Office of Anti-corruption and Integrity at ADB and the World Bank’s Integrity Vice-Presidency (Quibria 2017:8). However, these measures aimed at transparency and accountability come with substantial expenses and have been said to be often working at “cross-purposes with aid effectiveness” when they are designed with the intention of protecting donors’ reputation rather than being focused on achieving development results (Quibria 2017:8).

In a survey response given by 12 donors on whether or not there are significant differences in the agencies’ internal control and risk management practices based on the aid modality (i.e., if the funding is grant or contract, local or international NGOs, budget support, or grants to multilateral organisations) three reported having differing standards for different recipients. One indicated that its investigative functions would depend on the context of the aid investment, for instance, adapting operations when the countries have weaker law enforcement (Hart 2015:16-17). Two stated that they were “more likely to end funding to NGOs than to governments or international organisations if evidence of corruption were found” (Hart 2015:46).

Further, two of the three acknowledged that differences in the range of due diligence and monitoring would depend on specific agreements that they had with differing international organisations (Hart 2015:46). Overall, the survey responses provide a glimpse into the varying approaches across agencies on how they factor in corruption risk mitigation. With such contrasting processes across agencies, as well as varying operational contexts, “a stronger evidence base about the mechanisms through which development aid is subverted by corruption” could bolster donor attempts at safeguarding aid (Dávid-Barrett et al. 2020:482). A study analysing conditions under which donor interventions are successful in controlling corruption in aid spent by national governments through procurement tenders found that “an intervention which increases donor oversight and widens access to tenders is effective in reducing corruption risks” (Dávid-Barrett et al. 2020:485).

It is reasonable to assume that oversight and monitoring and corruption risk mitigation will come with financial costs that could be budgeted and accounted for in aid investments, though these activities may cover a range of needs, including but not exclusively focused on corruption.

For instance, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) has a Programme Operating Framework which lists its policies.On designing programmes, the framework states that appropriate budgets and high-level risks (including corruption) ought to be considered (FCDO 2022). However, it is not clearly discernible from the framework document how much would be allocated, or earmarked, for corruption risk mitigation in their assistance (more details in upcoming sections).

Differences between allocations and earmarking for anti-corruption

There is a difference between budget that is allocated for anti-corruption and earmarking within projects.

Allocations in the budget could include the sum of different inputs that can be badged together as ‘anti-corruption’. Whereas earmarking corresponds to purposefully reserving funds for a given activity.

When it comes to viewing earmarking in the context of anti-corruption, it can also act as a measure used by donors to mitigate corruption risks. For instance, when funding national administrations in high corruption risk environments, some project funds can be earmarked for potential mitigation measures of delineated corruption risks.

Even with respect to the other major agencies, there is limited information in the public domain on how much is allocated to anti-corruption measures within development programmes and how donors arrive at these figures. One good practice in this regard could be on having proactive transparency around budgets and expenditures (Rahman 2022:14). Open budgetary data that is publicly available in an open data format at a granular level can allow for disaggregation and tracking (Rahman 2022:15). Such an exercise could serve as an accountability mechanism for intended beneficiaries, civil society organisations (CSOs), journalists, etc., while simultaneously enabling better control for donor agencies in tracking their financial contributions to multilaterals and other aid programmes (Rahman 2022:14).

Thus, when it comes to understanding allocation or even earmarking for anti-corruption in official development assistance (ODA), there is little available data, and there seems to be no magic number, not least because arriving at these figures would be challenging.

Lessons from other mainstreaming initiatives could, however, be applied to the anti-corruption area as well. The Anti-Corruption Handbook for Development Practitioners by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MFA) of Finland when speaking of mainstreaming gender in their anti-corruption responses seeks to integrate it “at all levels into policy, goals and projects, and planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of activities” (Jokinen-Gavidia et al. 2012:204). Allocated budgets in such cases would then need to work backwards from the intended outcomes – accounting for activities, resources and staff needed (Jokinen-Gavidia et al. 2012:204-205). The same learning could be applied to earmarking for dealing with corruption risks in aid investments.

An imperfect comparison to understand how much can be kept aside for anti-corruption in ODA can be made with corporate compliance in the private sector. A 2018 business survey by the Risk Management Association found that 50% of corporates “said they spent between six per cent and ten per cent of their revenue on compliance costs, while another 20 per cent spent less than five per cent on compliance” (Alix 2018).

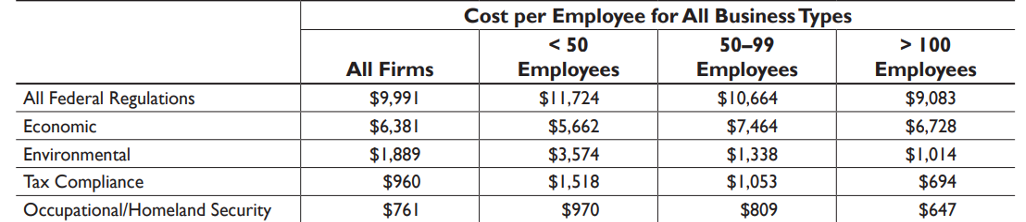

Another study by the Competitive Enterprise Institute found that large firms in the United States report that the average cost of maintaining compliance runs at US$9,991 per employee (Crews Jr 2018:17). These figures vary according to the size of the firm, as seen in the infographic below:

Figure 1. Regulatory costs in small, medium and large firms, 2012.

Source: Crews Jr. 2018:17

In the private sector, studies show that the cost of compliance is much lower than the cost of non-compliance for corporates. Ascent (2020) notes:

“The average fine for an enforcement action is $2 million, compared to the average cost of business disruption due to an enforcement action at $5 million, the average revenue lost at $4 million, and the cost of lost productivity at $3.7 million. In total, firms spend almost $15 million on the consequences of non-compliance. That is 2.71 times higher than what firms typically pay to stay in compliance by building strong compliance programs”.

Corruption has been cited as one of the largest impediments to receiving aid in some of the most challenging development contexts, such as south-central Somalia and Afghanistan (Harvey 2015). Despite this recognition of the challenge, allegations of major corruption cases continue to emerge, such as the recent one surrounding the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) where US$60 million of donor funds were misdirected to an entity to build housing in six countries – which did not materialise (Ainsworth 2022; Kapila 2022). Customising anti-corruption measures to a particular programme and consequently costing activities, and allocation or earmarking funds for context and project appropriate corruption risks in aid investments could be one way to manage these issues.

Select cases on how budgeting for anti-corruption in aid investments takes place

Having stated that there is limited publicly available information on allocation or earmarking in budgets for understanding and countering corruption risks in aid investments, this section aims to shed light on some illustrative methods by which donors budget for anti-corruption in their programmes.

Allocation to anti-corruption within donors’ programme level budgets

The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), in its report on the handling of suspicions of corruption and irregularities in international development co-operation (2019:14), lays out its focus on “providing support for accounting systems and systems for internal management and control, providing whistleblower channels and clearly showing that [they] never accept corruption” in their projects. There is, however, no indication of how much has been or should be allocated or earmarked in aid investments for this.

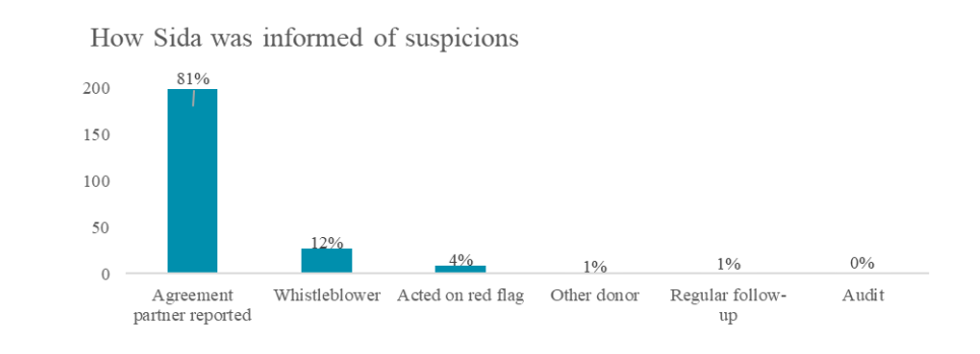

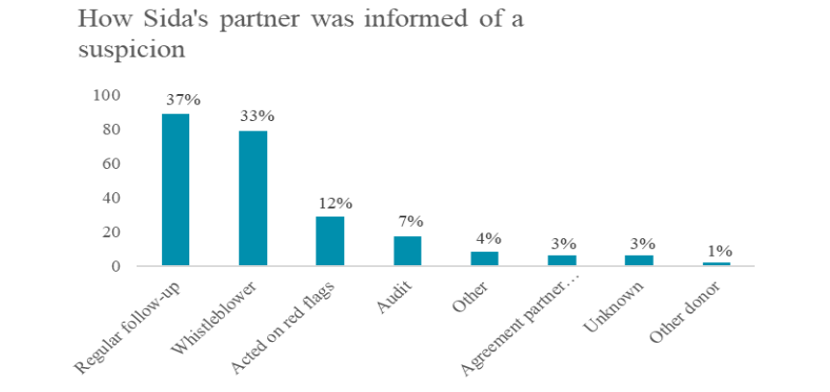

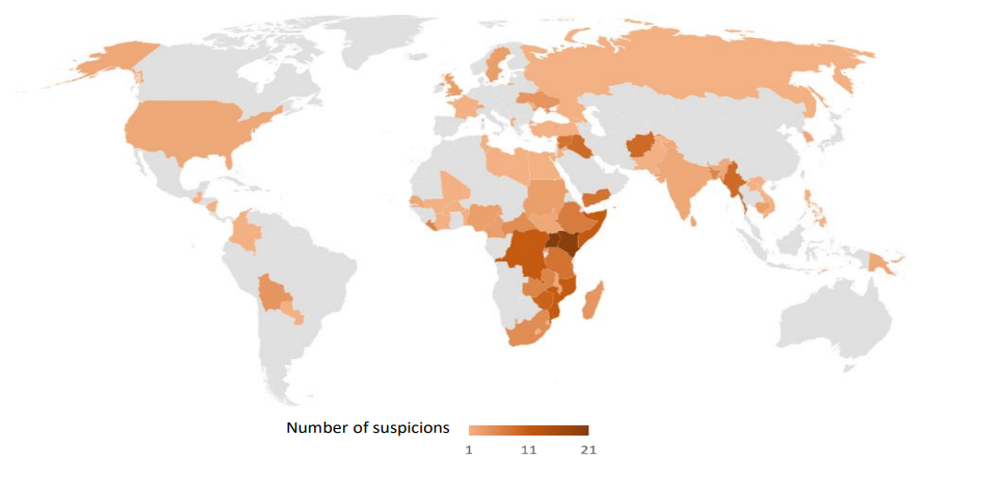

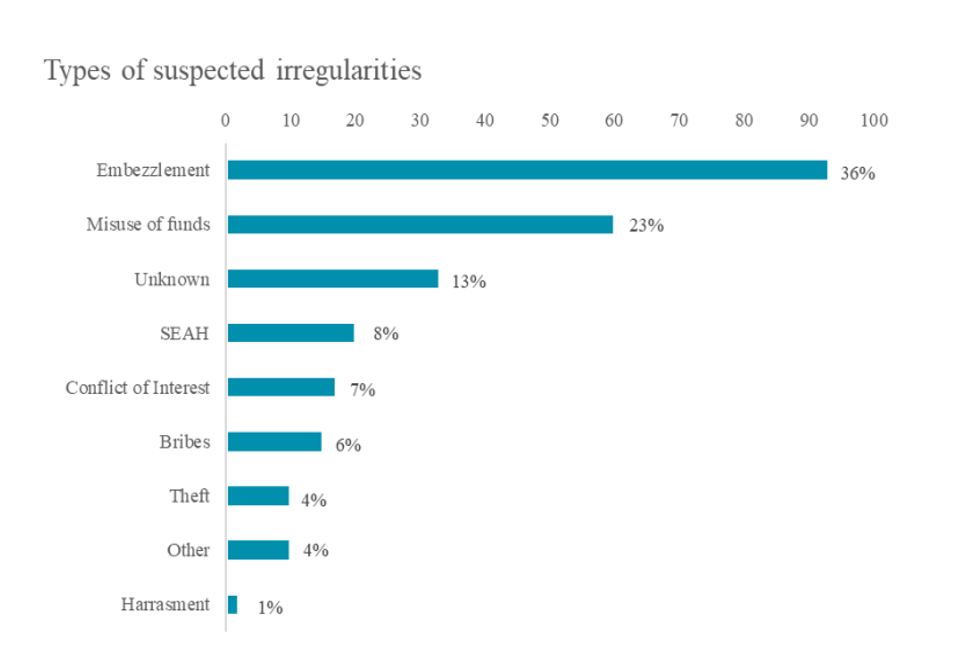

The report highlights noteworthy trends in terms of the process followed for handling suspicion, how the agency and its partners are informed of suspicious activity, geographical distribution of opened cases based on where the suspicion occurred, as well as the types of suspected corrupt activities (Sida 2019a:6-8,10,11). Please see the infographics below:

Figure 2a: How Sida was informed of suspicious activities.

Source: Sida 2019a:7,8

Figure 2b: How Sida's partner was informed of suspicious activities.

Source: Sida 2019a:7,8

Figure 3: Geographic distribution of opened cases on suspicions of corruption.

Source: Sida 2019a: 10

Figure 4: Types of suspicious activities.

Source: Sida 2019a:11

Top of FormThese metrics (discussed in the background section of this answer) could be useful in determining corruption risks depending on the context and project and, by extension, could inform support calculations on allocation or earmarking budgets for anti-corruption activities in specific investments and contexts. It is worth noting that Sida also provides information on suspicions of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH), which could be further used in understanding and mitigating gendered forms of corruption, such as sextortion, in programmes. Sextortion as defined by the IAWJ is “a form of sexual exploitation and corruption that occurs when people in positions of authority … seek to extort sexual favours in exchange for something within their power to grant or withhold. In effect, sextortion is a form of corruption in which sex, rather than money, is the currency of the bribe” (IBA n.d.).

The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (2022:10) seeks to ensure that reporting requirements and risk mitigation strategies are proportionate to the budget and size of the programme. Further, it adds that “at an early stage of design, an outline of the programme’s intended outcomes, operating context, activities, budget and high-level risks [including corruption] must be set out and approved at the appropriate level” (FCDO 2022:16-17). Budget lines are calculated as per the complexity of the programme as well the degree of scrutiny that FCDO seeks to apply to it (FCDO 2022:56). Programmes are also required to “consider and provide evidence” of their “impact on gender equality, disability inclusion and those with protected characteristics” (FCDO 2022:16). This shows that there is precedent in mainstreaming other cross-cutting themes, which could, in theory, extend to anti-corruption. Lastly, all decisions regarding programmes, including payments and monetary commitments, ought to be taken within “delegated budgets” which have to be in line with the agreed risk appetite (FCDO 2022:16). Once again, risk appetites would have to consider corruption, and could contribute towards calculating appropriate allocation, or earmarking, in specific programme budgets for anti-corruption.

Another avenue to shed light on the appropriate levels of allocation and earmarking in aid investment for anti-corruption is looking at total donor administration costs for programme implementation. While these figures cover all costs, including staffing, internal controls, compliance, etc., it could point towards the total sum available from which some could be allocated, or earmarked, for corruption risk mitigation within programme operations. A few donors’ administrative costs are as follows:

Australia: 8.5%

Canada: 8.3%

Germany: 4.7%

Netherlands: 10.96%

Norway: 7.7%

Sweden: 6.1%

United Kingdom: 7.3%

United States: 9.3%

Operationalising anti-corruption as a part of “doing good” within programmes

Anti-corruption as a cross-cutting issue is sought to be operationalised by the Norwegian MFA in its development policy and assistance. While there is a recognition of the zero tolerance policy (ZTP) towards corruption, there is also an understanding that “ZTP does not provide a fair share of the risk of operating in high-risk areas” the ceasing of operations due to sanctions following a ZTP approach could lead to negative impacts for the intended beneficiaries (Vaillant et al. 2020:22,23).

The MFA also seeks to follow a “do no harm” approach which it understands as being “operationalised as part of risk management, covering risk identification, analysis and mitigation” (Vaillant et al. 2020:24). According to Johnston (2010), such an approach involves “avoiding premature or poorly-thought out reforms that can do more harm than good – notably, steps that overwhelm a society’s capacity to absorb aid and put it to effective use, and that risk pushing fragile situations and societies into particular kinds of corruption that are severely disruptive”. However, an assessment report found limited examples of such a risk-based practice being followed (Vaillant et al. 2020:24,25).

In a staff survey at the MFA, 68% of the respondents concurred that, even in programmes that did not contain an anti-corruption focus, there was an inclusion of anti-corruption elements as a part of operationalising a “doing good” approach (Vaillant et al. 2020:25). The “doing good approach” is based on identifying and aiming to reinforce positive effects with respect to anti-corruption and other cross-cutting issues (for example, gender) and even including them as standalone components in projects (Valliant et al. 2020:17). Evidence for this was found in the MFA’s aid investments in Somalia in the sectors of oil for development, fisheries and forestry (Vaillant et al. 2020:25). How much was being allocated to anti-corruption in each of these sectoral programme budgets remains unclear.

Using a risk matrix to support allocation for anti-corruption

A risk matrix could help in understanding the main corruption risks for a given project based on the context of its operation. Such evaluations could then aid in calculating earmarking amounts in project budgets for corruption risk mitigation.

The Sustaining and Accelerating Primary Health Care in Ethiopia (SAPHE) programme by the FCDO, for instance, has its own risk matrix that covers “operational, fiduciary and corruption, and, environmental and social risks, trend analysis of identified risks, actions to either treat or tolerate or transfer the identified risks and as well as threshold triggers for the identified risks” (FCDO 2017). The risk matrix is put together with risk assessments conducted by external partners (for example, World Bank, Global Fund and USAID, European Union, etc.,) to produce a risk assurance plan. These plans then delineate “performance, financial management, procurement and supply chain and governance related risks and mitigation measures with objectively verifiable milestones” (FCDO 2017). Once again, it was not clear how much was allocated or earmarked for these processes in the programme budgets.

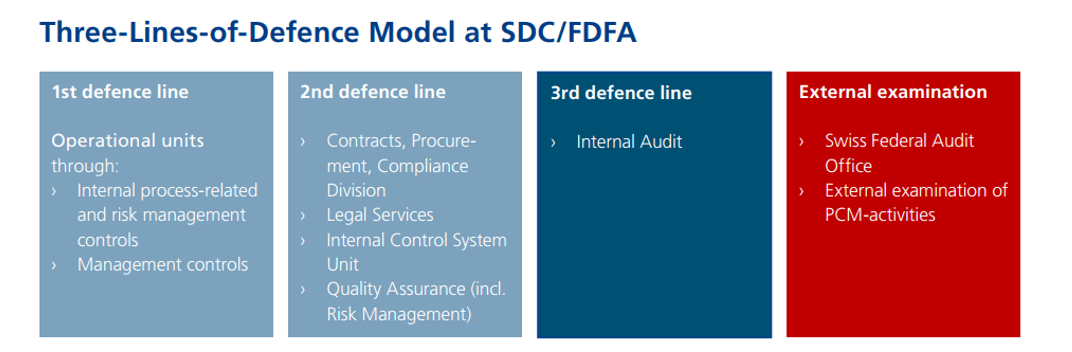

In the case of Switzerland, the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) have developed a “three lines of defence model” (see infographic below):

Figure 5: Three lines of defence for SDC/FDFA.

Source: SDC (n.d.: 23).

As a part of the first line of defence, in operational management, project risk assessments are carried out with a close monitoring of budget controls, field visits and participation by steering committees. When dealing with external agencies, particular importance is given to the PRA (partner risk assessment), which is a standard SDC institutional requirement to minimise risks and to “get to know” the partner (SDC n.d.: 23).

Given that the risks for aid being abused depends on what is being delivered, i.e., budget support or direct service delivery programmes, there ought to be a collective understanding of risk appetite and risk sharing between all stakeholders involved in programmes, especially in cases of multi-partner funds. These stakeholders could include the funding partners, a multi-partner fund administrator, the implementation partners, national authorities and intended beneficiaries (Disch and Sandberg Natvig 2019:25).

Having clear guidance on how to protect development funds from corruption

The various stages of the contribution management process, as well as the recommendations on governance and internal control, provide guidance on preventing corruption in Swedish aid funds. For instance, detailed advice on risk assessments, budgeting and site visits is given. A foundation for curbing corruption in contributions is laid forth by the lessons learnt from prior corruption cases (Sida 2019b: 1).

Use of conditionality

A much higher level approach is the use of conditionality related to corruption controls within programmes.

Germany, for instance, through its BMZ 2030 strategy aims to focus on partnering with countries that “are willing to implement targeted reforms regarding good governance, human rights protection, and fighting corruption” (BMZ 2020).

As a part of the strategy, countries receiving direct official aid that have not shown reforms have been excluded, reducing recipients from 85 to 60. Development cooperation in excluded countries would nevertheless continue through multilateral and civil society channels supported by Germany (BMZ 2020). Such a strategic focus could provide incentives for mainstreaming anti-corruption across programmes while signalling steps towards earmarking for corruption risk mitigation in aid investment.

An assessment of a country partners’ commitment to and progress in curbing corruption is also included within Partnership Principle III of the UK’s aid conditionality policy (PPIII: Commitment to Strengthening financial management and accountability, and reducing the risk of funds being misused through weak administration or corruption).

Summary

Approaches on allocating funds for anti-corruption within programmes, or earmarking for corruption risk mitigation, vary between donors. There is acknowledgement of the importance of integrating anti-corruption in development programmes. For instance, survey results and interviews with U4 partner agencies reveal that they “consider corruption to be a crosscutting issue” (Boehm 2014: 3). Aid leakages not only hamper the intended project outcomes but in certain national contexts can further exacerbate the corruption challenge (e.g., the aforementioned example of Afghanistan). Thus, there is a need for budgeting for corruption risk mitigation within projects.

Also, integrating anti-corruption measures into sector work needs to go hand in hand with standalone anti-corruption efforts at other levels. For instance, support towards anti-corruption laws or agencies, or aimed at broad procurement reforms (Boehm 2014: 4). Lastly, experts suggest conducting rigorous impact evaluations, that go beyond anecdotal evidence, to determine whether or not measures to integrate an anti-corruption perspective into a given programme or sector has been successful (Boehm 2014: 4). However, it must also be recognised that, irrespective of activities and budget allocations, the effectiveness of donor corruption mitigation measures in programmes is challenging to assess. This is due to the illicit nature of corruption, which makes it difficult to quantify. Public availability of such assessments could also be limited due to the often politically sensitive nature of these documents.