Introduction

Over the past two decades, advances in information and communication technology (ICTs) have transformed the way people access and interact with the information that governments produce and hold. The development of online digital portals to enable users to submit requests for information, under Right to Information (RTI) legislation, is one of many examples of these changes (Fumega 2014).

Arguably, ICTs would help to increase the efficiency of the publication process as well as the way requesters access information. In the digital era, transparency may well be what people see on their computer screens (Meijer 2007). However, governments did not always develop technology to facilitate such processes on their own and, in many cases when they did, they were not the first to do so.69930387bfb2 In 2006, Phil Rodgers and Francis Irving developed the basics of the website whatdotheyknow. The idea was simple: a piece of software that would allow citizens to issue RTI requests. In 2008, the British non-governmental organisation My Society pushed forward the idea and fully developed the website. This approach was novel for several reasons: it did not require government’s consent, and it was developed based on free-software.39e81a20f61f The rationale behind the project was that citizens would ask information through a single portal and the government would reply, eliminating the need to know the email address of each mandated agency. According to the My Society Research Unit, 15-20% of British RTI requests are currently issued through My Society portal (Rumbul 2016).

Following the steps of that initial development, an emerging group of civil society actors have deployed RTI portals in at least 22 countries, allowing citizens to make requests online. Civil society organisations and individual developers have not asked for government permission to set up these portals. Thus, they have built these websites, enabled by open/free source software, and have targeted government email addresses. These portals allow users to not only issue requests by accessing just one site – no matter the agency or topic – but also without having to search for email addresses. Further, these portals usually present a feature of proactive disclosure of all responses in order to allegedly improve the efficiency of the procedure allowing users to monitor requests, as well as setting up a knowledge repository where all requests are centralised. As more portals are set up, a pertinent question for all these portals relates to the relationship between these portals and the actual improvement of RTI regimes, as well as the dissemination of the exercise of the right to access information.

This paper analyses RTI online portals developed by civil society organisations in five countries with different traditions and at different stages of implementation of the RTI legislation. We selected these cases to explore the effect, if any, of RTI portals on RTI regimes.fc7bdc0a3429 First, we provide an overview on how actors and technologies evolved at the global level and offer a set of basic definitions. Next, we analyse each of our cases following a comparative framework that we have developed. We then discuss the role of requesters, government and enforcement institutions. Finally, we provide a set of recommendations to donors and other organisations based on our cases and the available literature. We argue that portals play a meaningful, but limited, role in improving RTI regimes. We note that the sustainability of these initiatives requires new ways of understanding the role of civic tech organisations in RTI regimes. We draw attention to the fact that without these portals, some of the positive changes in these RTI regimes would not have materialised.

2. Right to Information regimes: what's new in the digital age?

2.1 Right to Information arenas

Right to Information (also referred as Freedom of Information or the Right to Know) is a very basic, powerful, and relatively old, concept. The right establishes that every individual should have access to government-held and produced information, except in very specific circumstances. A RTI law mandates that government agencies proactively publish basic information about their activities and establishes the right of every individual to ask for public information. This has been the result of a long quest by civil society advocates around the world, gaining momentum in the USA with the famous Harold Cross Report (Cross 1953)41aa73427068 and continuing through the 20th century. The period from the early 1990s to late 2000s, also known as RTI advocates “Golden Period”,4d11934bd681 witnessed the expansion of national RTI laws from 13 to over 72 countries in 2011 (Vleugels 2011) and over 100 by the end of 2015 (Banisar 2015). Despite this increase in numbers, there is consensus that implementation of these laws across the globe has been poor in many cases (Darbishire 2010, Hazell, Worthy and Glover 2010, Fumega, Lanza and Scrollini 2013). In short, while passing a RTI law is an important step, it is far from being sufficient for a successful RTI regime. However, researchers in this field note that there are only a few studies systematically assessing the impact of RTI in governance (Bailur and Longley 2014).

The development and implementation of RTI portals by civil society provides an excellent starting point for understanding the potential effects of these portals on right to information regimes. RTI regimes are a system of institutions, actors and practices dealing with the exchange of official information between the state and society. RTI laws create a new, and often contentious, type of relationship between government and civil society. They are the foundation for RTI regimes or arenas (Scrollini 2015), where several actors interplay to access and use public information. Conflicts and disagreements about who gets the information, when, and how, are common in these information arenas, but there are several ways in which government and other actors could manage this conflict. Nonetheless, in order to understand how these regimes work, it is necessary to consider factors such as the emergence of these regimes, the professionalism of public bureaucracy and the role RTI enforcement institutions play.

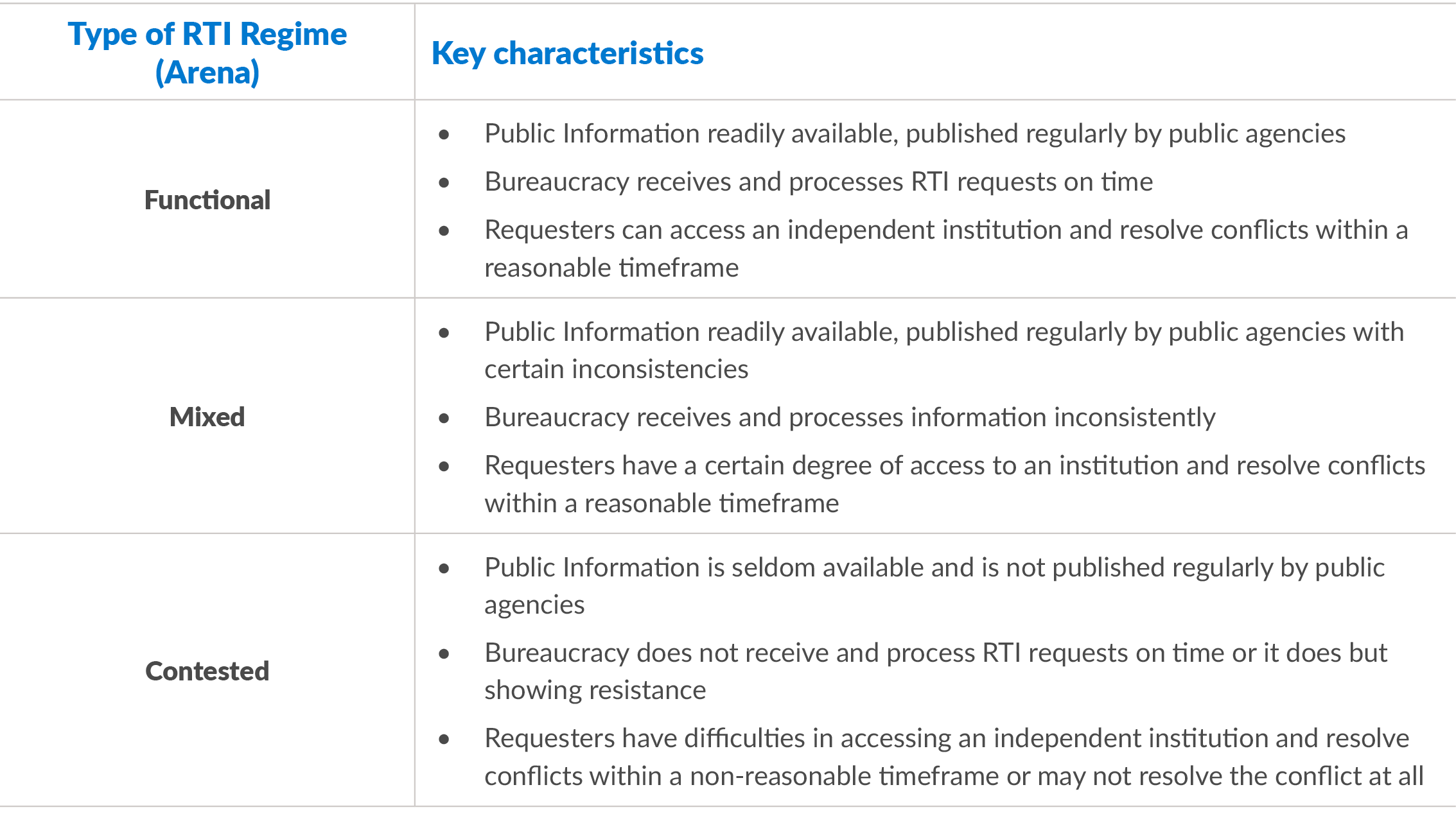

It is possible to distinguish between several types of regimes according to their outputs. The following table presents an initial typology of RTI regimes based on three outputs: the proactive availability of public information, the efficiency in answering RTI requests, and the effectiveness to resolve disputes.

Source: Scrollini (2015)

2.2 The role of Right to Information portals

RTI portals are a vital aspect of any RTI regime: the availability to request and obtain official information. Even though these portals mainly contribute to the reactive disclosure of official information, the evolution, dissemination and use of these tools could also contribute to other outputs such as the publication of proactive information as well as the general understanding of RTI regimes.

Digitalisation leads to a larger number of requests received via email and other digital tools from mandated bodies, as well as more information proactively published online compared to paper-based systems. Thus, RTI arenas are becoming an environment where information is relatively easy to store and distribute, in a cheap and efficient way (Scrollini 2015). While there may be value in the distinction between offline and online systems (see, for instance, Bailur and Longley 2014), digital and offline services seem to be converging in both developed and developing countries.436a661a5af6

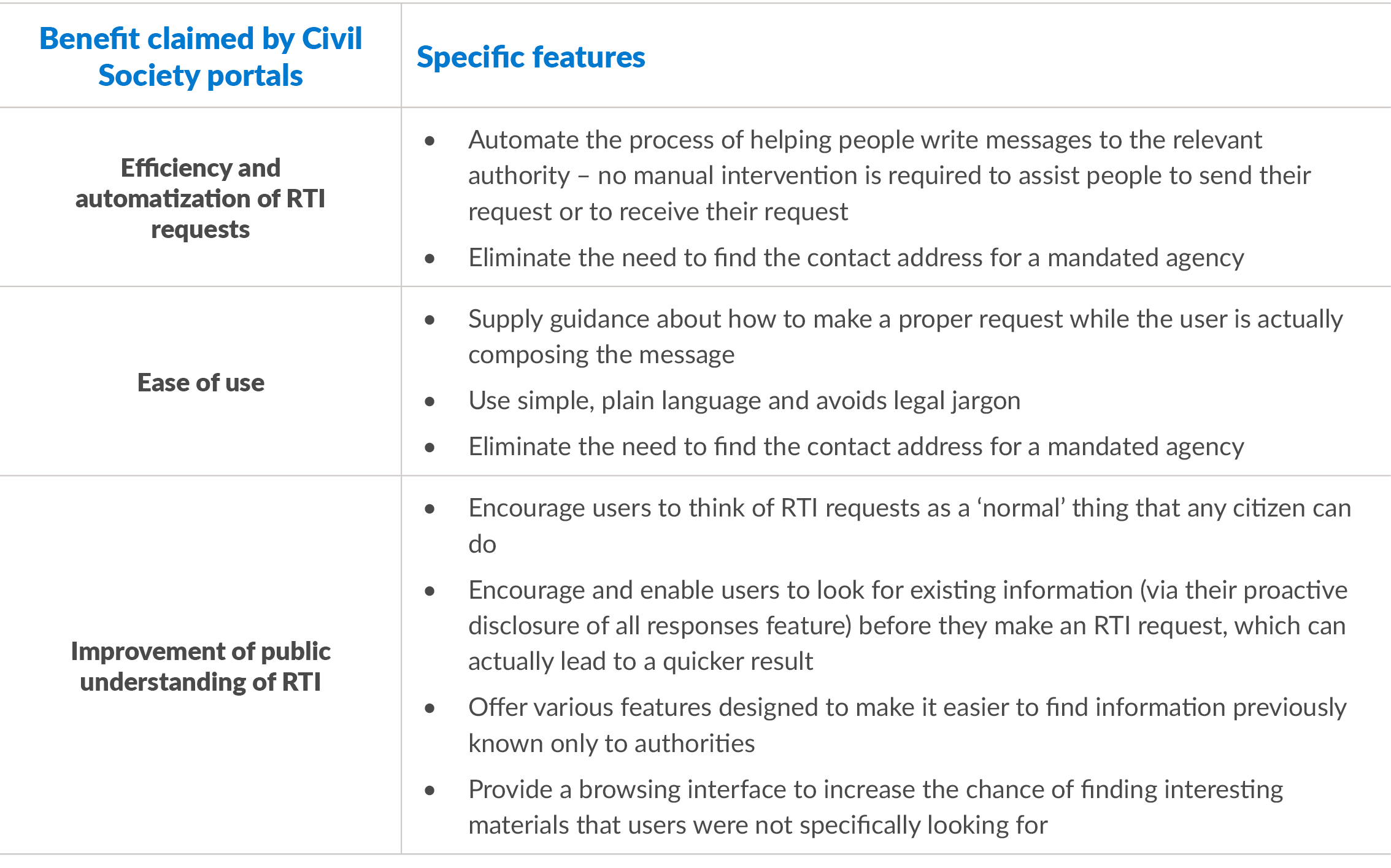

RTI portals are supposed to increase the efficiency of receiving and processing requests. Governments and civil society across the globe have developed these portals with the goal of increasing efficiency and effectiveness. According to Bailur and Longley (2014), RTI portals such as Alavetelibd75797591a5 bring a series of benefits, outlined below.

Source: Authors’ adaptation based on Bailur and Longley (2014)

The current technological landscape offers several alternatives based on either closed or open source software to developing these portals.0dab860d242f There are other alternatives based on closed source software. Further, commercial ventures sell RTI-related software to governments. The following table provides a list of some of the most popular technologies run by civil society organisations:779e37a73003

2.3 The role of public administration

According to existing literature, governments usually react to ICT innovations in two different ways. On one hand, they can create an enabling environment and cooperate with requests received through the external systems. On the other hand, they can develop alternative government-controlled systems for managing requests and reports from citizens (Davies and Fumega 2014). When governments develop their own systems, they usually set up closed software portals and do not incorporate innovations developed by open-source portals. In many cases, responses are not proactively disclosed for every user to check (however, there are exceptions to this such as the Mexican official portal).0c77ca439610

However, we argue that governments can react to the introduction of RTI civil society-led portals in two additional ways. After accepting and working with the civil society portal, governments may decide to build their own portal. Alternatively, governments may choose to resist and ignore the portals.

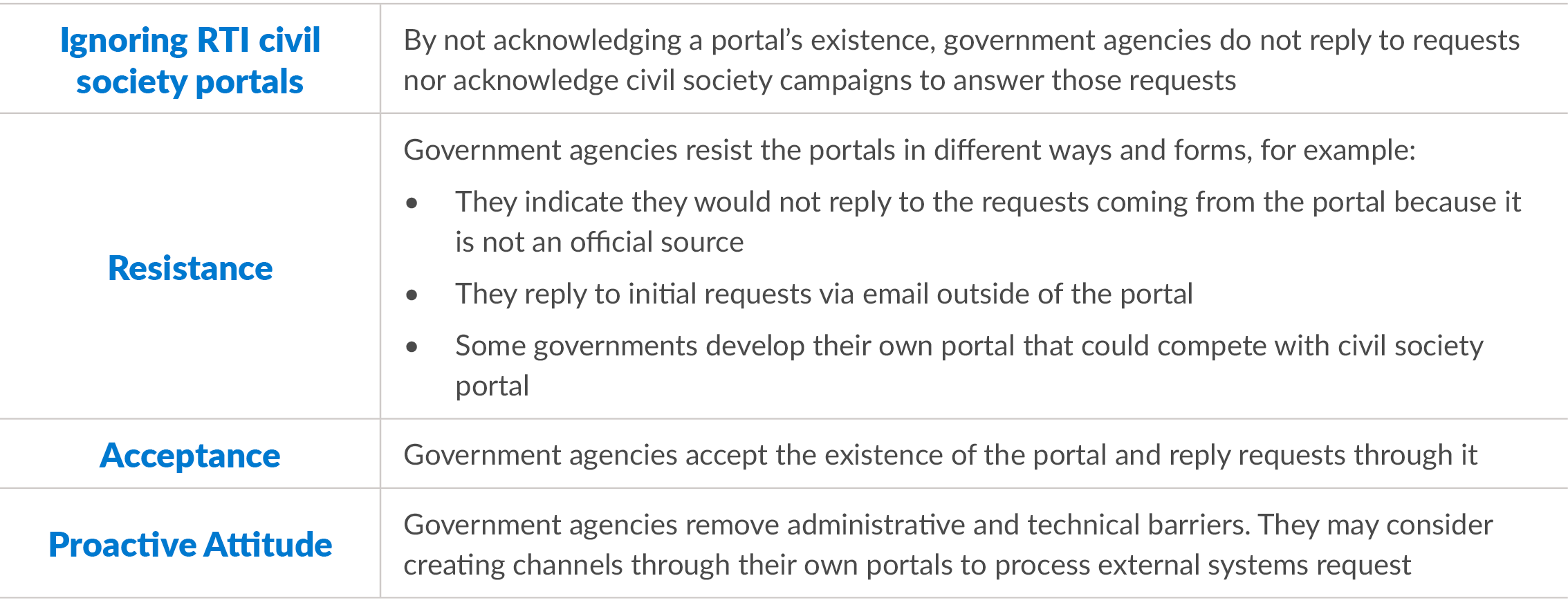

Governments are not monolithic entities and different agencies within a government might have different reactions to a RTI portal. As the implementation of the portal evolves, and the interaction between civil society actors and public officials increases, agencies might shift attitudes. Outlined in the table below are possible attitudes from agencies:

Source: Fumega, Scrollini and Semsrott (2016)

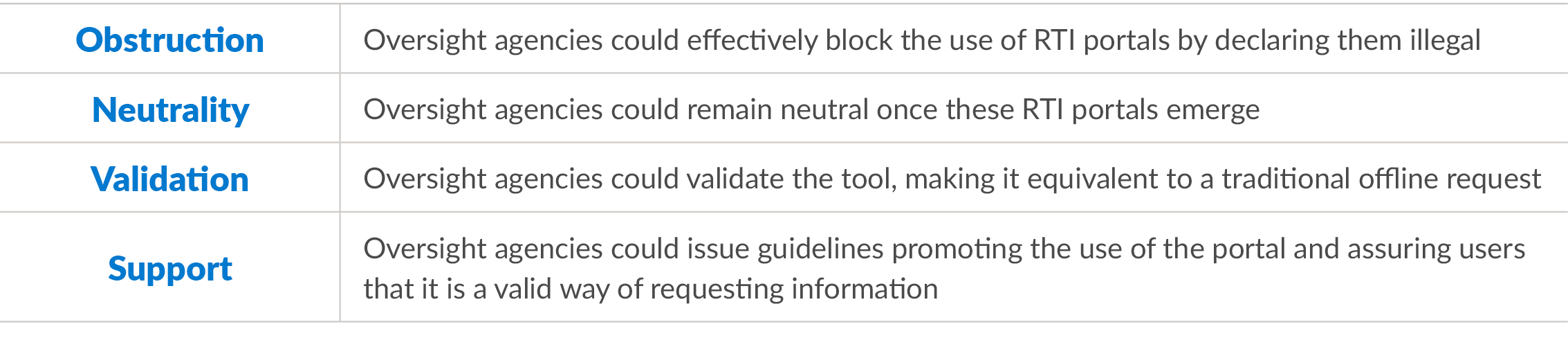

Another key actor in a RTI regime is the oversight agency that is responsible for the implementation of the legislation. Oversight institutions could react to the launch of civil society-led portals in different ways. There are four particular attitudes that these agencies could adopt, as follows:

Source: Fumega, Scrollini and Semsrott (2016)

These behaviours are likely to be linked to the kind of regime where a particular RTI portal is introduced. Variables, such as the structure and capacity of public bureaucracy and the independence of oversight institutions, are key factors to understand different reactions.

2.4 Changes Right to Information portals bring to these regimes

It is difficult to measure the impact of RTI websites (Bailur and Longley 2014). Our aim in this paper is to understand if and how these portals changed the behaviour of public authorities and whether they improved the entire RTI regime. We view these portals as an intervening variable in already existing RTI regimes and document whether the introduction of this variable modified or not the behaviour of involved actors.

We avoid discussing the ‘impact’ of these portals for two reasons (Fumega 2016):

- In order to answer whether portals contributed to a more ‘transparent’ polity, a ten-year period is needed between the project and its evaluation. A more articulated hypothesis or theory of change is also required but so far, none of these portals have developed such a theory beforehand. Further, this astringent way of considering impact might not even be applied to RTI laws themselves (or several policies for the matter).

- Methodologically, we look at qualitative changes in a RTI regime. We track behavioural challenges produced by the RTI portal in the cases introduced in the following section, similarly to the outcome mapping methodology (Earl, Carden and Smutylo 2001).

3. Case studies

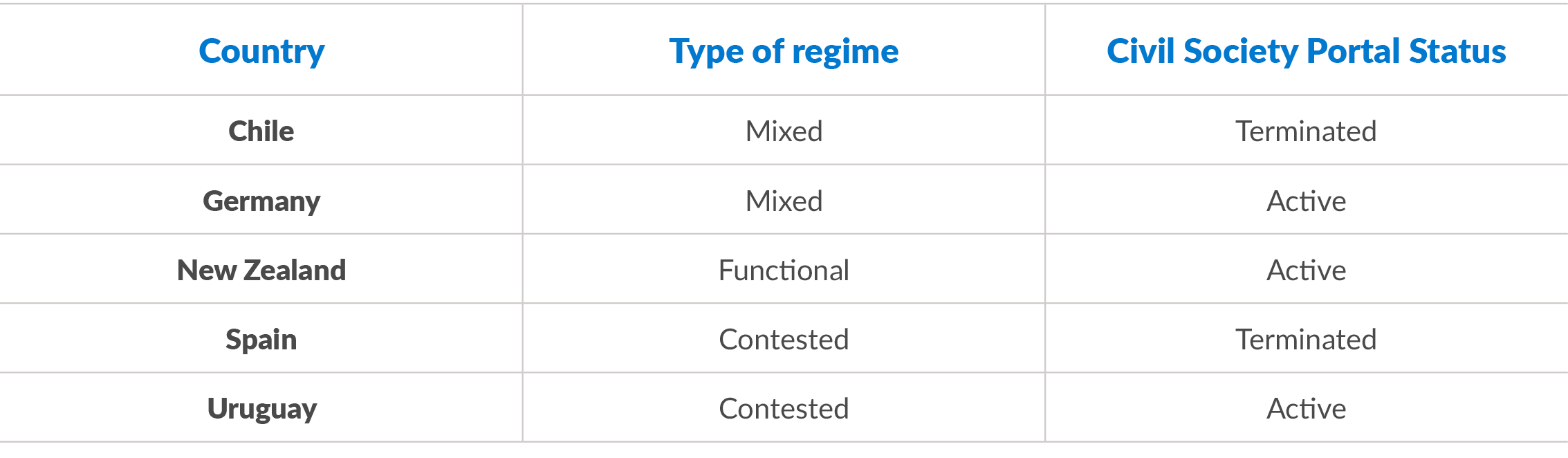

In this section, we look at five cases1a905bdf08d0 where RTI portals were implemented by civil society organisations. The cases encompass a mix of developing and developed countries and different types of RTI regimes and both active and terminated cases are examined. Although not a representative sample, the cases provide a good description of contributions and challenges ICTs projects face.

Chile, Germany, New Zealand, Spain and Uruguay were selected because in each case, civil society organisations developed and launched a RTI portal before governments created their own. These countries present differences in terms of oversight institutions, RTI legislation, and institutional traditions.These differences allow us to explore how these portals adapt to a diverse set of environments.

A “maverick” developer based in New Zealand, designed the first Alaveteli portal outside the United Kingdom in 2009. The website FYI (For Your Information) became a new channel through which to issue information requests. The civil society portal has run smoothly in New Zealand, although it faced initial resistance from a few authorities. The portal helped to uncover several government practices (including the questionable practice of heavily redacting or “blacking out” replies) from New Zealand government (Caleb 2015).

In Chile, a local NGO (Smart Citizen Foundation/Fundación Ciudadano Inteligente/FCI) developed an RTI web portal (Smart Access) in 2011. This portal allowed users to request information online under the Chilean RTI legislation, which was enacted back in 2009. The portal gathered initial traction and led the government to build its own in 2013.

The same year as the launch of the Chilean portal, FragDenStaa (Ask the State) was developed by a civil society organisation in Germany. Currently, approximately half of RTI requests in Germany are filed through this portal. The online tool has allowed for changes in public agencies response patterns, which are currently adopting a more open and receptive approach but many challenges still remain.

More recently, in 2012, a Uruguayan NGO (Data UY) launched a portal based on the British software, Alaveteli. The portal was designed to allow users to submit RTI requests and targeted public authorities’ emails. Despite resistance from public officials, it has prompted Uruguayan authorities to acknowledge emails as a legal way to request public information. It has also recently triggered the initial development of a government RTI portal.

In Spain, Tu Derecho a Saber (Your Right to Know) was a civil society- developed portal aimed to reduce barriers between public agencies and information requesters. Two Spanish organisations, Access Info-Europe and Civio, who have been collaborating in different civic technology projects, developed the project (Access Info- Europe 2015).

In the following sub-sections we introduce details of the selected cases, as well as some relevant features of these civil society-led RTI portals.

3.1 Chile: Smart Access (Acceso Inteligente)

Background

On September 19th 2006, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued an important decision in the case of Claude Reyes v. the State of Chile. The Court recognised that public access to information was essential to democratic participation and freedom of expression (Open Society Foundations 2009). This case provided the foundation for the debate and enactment of the Chilean RTI law in 2009.

A couple of years after the enactment of the Chilean RTI law, the first civil society led web portal with the purpose of centralising information requests to the Chilean government, Acceso Inteligente(Smart Access), was developed by Fundación Ciudadano Inteligente (Smart Citizen Foundation, FCI).

According to a report carried out by FCI for the Open Society Foundation (OSF), during the first years of implementation, the Chilean Transparency Law presented barriers for users requesting information. Some obstacles related to the variety of government websites: each presented a different access to public information form. This multiplicity of channels made requesting information online a difficult matter. Thus, FCI decided to build a portal to send a unique public information request form to multiple government agencies (Fundación Ciudadano Inteligente 2011).

The portal aimed to not only ease the process of requesting information to the Chilean government but also to raise awareness about the right to access public information. The portal presented two main components: 1) citizen requests for public information and, 2) a repository of information from all previous requests managed by the portal. The goal of the repository was to contribute to the monitoring and evaluation processes of the access to information regime.

Reactions

Acceso Inteligente was designed to allow any person to submit requests and then also access the portal to check the documentation of all previous requests and responses.Further, information about when the requests were made and how the government responded was available. These changes were an update to the features of the previous Council of Transparency’s portal, through Acceso Inteligente.

After the portal was launched, its progression was not as smooth as developers imagined while designing it. According to a FCI report, the actual implementation of the portal faced multiple technological and non-technological challenges as some public agencies received the request by email and others through paper forms. According to FCI, the Chilean government initially resisted the idea of a unique site for requesting information because the website “may encourage citizens to request more information than they usually do” (Fundación Ciudadano Inteligente 2011).

Developing a portal that was capable of sending requests to different public agencies and ensuring all requests were received and answered was not an easy task. To bring all the information into a unique civil society site, FCI developers needed to design a complex system flexible enough to be able to send the request in different formats. Once an individual submitted an information request (according to the law 20.285), Acceso Inteligente automatically connected the request to the appropriate public agency. The system would take that request and transform it into to the format that particular agency required. The mandated agency replied to Acceso Inteligente and the information was delivered through the system to the requester.

In 2011, to complement their work on the field of RTI in Chile, FCI signed an agreement to collaborate with two other Chilean NGOs, Pro Acceso and ProBono, in the submission of appeals to the Council of Transparency, the oversight body (Fundación Ciudadano Inteligente 2012).

According to an evaluation report of Acceso Inteligente, commissioned by FCI, 2,823 users registered to exercise their right to access public information through the civil society portal over a period of four years. Further, Acceso Inteligente processed 2,779 requests for public information from 537 government agencies and, according to their dataset, 80% of the requests received a response (Marshall 2013).This civil society-led portal provided the foundation for the 15,000 requests processed through the current Transparency Portal.

In 2013, two years after the development of the portal, the Council of Transparency, the RTI oversight agency, launched its own website. However, the requests and responses were only publicly accessible if the agency in question proactively decided to publish them. Before the development of this portal, the Council for Transparency examined several websites including the Mexican Infomex portal and the Chilean civil society-led portal, Acceso Inteligente. As work began on portal design, the Council invited FCI and twelve other stakeholders to participate in a series of roundtable discussions, known as “active listening sessions”, to share their knowledge and feedback (Fumega 2014).

The current official Transparency Portal, developed by the Council of Transparency and the General Secretariat of the Presidency, launched in 2013, several years after the country’s Transparency Law was enacted.

In 2015, FCI temporarily suspended their website and recommended that users submit their requests via the Transparency Portal of the Chilean Government. However, after a few months, Acceso Inteligente’s website was no longer available and the project was terminated.

3.2 Germany: Ask The State (Frag den Staat)

Background

The national German RTI legislation was enacted in 2005, after being on the policy agenda for approximately seven years. Despite bills already existing at the local level, in states such as Brandenburg and Berlin, it took pressure from civil society organisations and MPs to draft a national bill (Schoch 2016).

The national law presents several weaknesses, despite innovations in the RTI field coming from local governments.7a650fd46b17 According to an evaluation of the Institute for Regulatory Impact Analysis and Evaluation (Institut für Gesetzesfolgenabschätzung2013), some problems relate to overloading fees, poor responses to the requests, and large amount of undisclosed information.

When the portal was first developed, it had three main goals: 1) to promote the use of the RTI law; 2) to simplify the process of filing a request;f380fd35629d 3) to produce changes in the attitude of public officials by proactively displaying all the responses (or lack thereof) for everyone to see.

Reactions

After the launch and media coverage of the online portal, request numbers rose significantly from less than 2,000 requests per year, to 9,376 requests in 2015 (German Ministry of Interior 2016). Up until July 2016, 7,460 users visited the website to file 17,322 RTI requests (Semsrott 2016). Approximately 40% of all requests to federal mandated bodies are processed each year via the online portal, FragDenStaat.

FragDenStaat was initially advertised as a tool to reduce the workload of public official because the proactive publication of all the responses would avoid multiple requests on the same topic. However, the tool actually increased the amount of requests received by officials. A parliamentary assessment of the RTI legislation mentioned some frustration coming from public officials with regard to some of the features of the portal:

"[...] authorities criticized the RTI portal FragDenStaat.de, which it is used more and more by citizens, because it would publish personal data without the authorities knowing about it and because it prevented requesters from directly interacting with authorities. [...] Also, they are sceptical about disclosing information about their registers and lists" (Institut für Gesetzesfolgenabschätzung 2013).

According to Arne Semsrott, from Open Knowledge Germany, the portal led to two main changes regarding proactive transparency, regarding copyright and proactive disclosure of information:

1) Regarding copyright and publishing claims held by public authorities

In 2014, the Ministry of Interior (the RTI enforcement agency), sued FragDenStaat for illegally publishing an internal report on the constitutionality of an election law. The Ministry gave out this report in response to an RTI request however, it was forbidden to re-publish it for copyright reasons. A Berlin court ruled that the Ministry could not claim copyright on that document (Semsrott 2016). To avoid this type of claim in the future, a feature on FragDenStaat can be unlocked that enables other users to request the same information with only one click.

For example, 850 people requested the list of participants of the 60th birthday party for the Deutsche Bank manager Josef Ackermann, held in Angela Merkel’s Chancellor’s Office, through FragDenStaat until the authority decided to lift the ban. After that, bans on publishing have rarely happened.

2) Transparency of the German Parliament’s research section

In 2015, the Federal Administrative Court decided that the Parliament was mandated to disclose thousands of reports when asked via a RTI request. In response to this, FragDenStaat unsuccessfully pushed for the proactive publication of all parliamentary reports on a large variety of topics – from UFO sightings to human right abuses in China. When FragDenStaat acquired a title list of 5,000 reports conducted between 2005 and 2015, it developed a tool that made it possible for users to search the database of report titles and request individual reports with only one click.

Within three weeks of the campaign in January 2016, more than 2,000 citizens requested reports. Following the public pressure, the Parliament decided to publish all reports of the Research Section on February 16, 2016 (Semsrott 2016).

Nevertheless, some challenges remain. Some Ministries still refuse to answer requests coming via FragDenStaat as they still argue that the website is “not a proper email provider” and/or that they only answer via postal services. This has led to about 500 requests not being pursued further because requesters refused to disclose their postal address and identity. It remains a contested issue by the ministries, despite public support from the German Commissioner on Access to Information.

3.3 New Zealand: For Your Information (FYI)

Background

New Zealand passed its RTI law (Official Information Act -OIA) in 1982 . The law was designed to gradually include the principal of openness across the state. The law was the result of a long campaign by civil society advocates and emerged after the Ombudsman recommended the security and intelligence services be reformed.

New Zealand’s OIA was subsequently reformed several times, expanding its scope and increasing the robustness of the regime. New Zealand exhibits problems in terms of RTI implementation (most notably, the absence of statistics from 1987 onwards), as well as issues in delays and resistance from the bureaucracy to release information. RTI oversight agency (the Office of the Ombudsman) only holds recommendation powers (non-binding powers to force the administration to release information), however, to date, its recommendations have been followed and implemented.

In recent years, the Ombudsman has warned about deterioration in the quality of the RTI regime, due to the overwhelming demand for its services (Donnelly 2012). There is also evidence of worrying behaviour, such as hiding information from the Ombudsmen, by some agencies (Donnelly 2012). Nonetheless, New Zealand remains a functional regime where institutions seem to work in a consistent way (Scrollini 2015).

New Zealand developer Rowan Crawford started a project to resolve some of those issues. He designed and implemented “For your Information” (FYI) in 2009. The website was the first use of Alaveteli outside the UK. Concerns regarding the lack of innovation in RTI legislation implementation and general concerns about OIA not performing as expected motivated the development of the portal (Crawford 2013).

FYI was developed with the support of individual donations and contributions. Crawford largely worked alone in the development and implementation of the portal, although he received some support from colleagues at the Open NZ group and the Open Knowledge Foundation (Caleb 2015).

Reactions

Despite media attention after the launch of the RTI portal, there was no organisation available to host FYI.org.nz. Crawford’s initial vision was that after the launch and implementation of the portal, the NZ government would take over and make it an official channel to request information (Caleb 2015). However, governmental support never materialised and he continued working on the website on a volunteer basis.

Crawford recruited volunteers to handle some operational aspects of the website. Users contributed e-mail addresses from several New Zealand administrative agencies, as well as helping keep the database updated. Eventually the website received the support of one of the largest newspapers in NZ, The New Zealand Herald, which contributed towards costs of the maintenance of the site. Furthermore, the website earned a national prize at the prestigious technical community New Zealand open source awards. In general, the government did not resist the website, with the exception of a few government agencies, most notably the New Zealand police.

The RTI oversight institution (the NZ Ombudsman Office) not only accepted the website, but also produced an official guide for NZ public authorities on how to deal with FYI.org.nz requests. FYI website requests have been used in diverse ways; to get information from security agencies, such as the Police, and even as evidence in the New Zealand Human Rights Tribunal. Up until October 2016, the website processed 4600 requests, covering 3041 authorities from 1500 users.

3.4 Spain: Your Right to Know (Tu derecho a saber)

Background

Although an electoral promise from 2004 (Anderica Caffarena 2013), Spain waited until 2015 to enact a RTI law. Spain was, at that time, the only country in Europe with over a million inhabitants without a RTI law. Thus, requesting public information was not an easy task. Two Spanish civil society organisations, Access Info-Europe and Civio, built a web portal that enabled users to request government-held information. The project aimed to create a simple tool for anyone to request information about the performance of a public institution.

Tu derecho a saber (Your Right to Know) was launched in 2012, at the same time as the presentation of the first draft of the RTI bill. The project was funded by small individual donations, via Goteo, a crowd-funding website. The portal – Tu derecho a saber – was built using the British Alaveteli software. The same team (Access Info and Civio) had earlier launched Ask the EU, a website through which individuals could request information to any institution of the European Union.

The idea behind the project was simple, the user would send a request via the portal, it would automatically reach the appropriate agency and be published on the portal. When the agency sent an answer, it was automatically published on the public web portal. After receiving the information, the user would comment on the response and decide to send a clarification and/or more information.

The project presented two main goals in two different stages. The first goal was to highlight the need to enact a RTI law, promised since 2004. Later, after the initiation of the RTI law, the website would make the process for requesting information online easier for the user. The immediate publication of the responses promoted the dissemination of public information (Cabo 2012).

Reactions

The website faced many challenges and the lack of response to requests was higher than in any other RTI portal. In 2012, the institutions ignored 54% of the applications received through the portal and in 2013, agencies left 81% of requests for information unanswered. Throughout 2014, during the debate of the RTI bill, administrative silence fell to, a still very high, 42%. Despite the high percentage of unanswered requests, citizens were able to access information, such as the number and the annual cost of interpreters in the Senate, the number of applicants for pardons, unstandardized Defence Ministry budget deviations and the cost of the coronation of Philip VI (El Confidencial 2015).

Tu derecho a saber has been an instrumental advocacy tool to amend significant gaps in the RTI Law. In 2013, more than 180,000 people signed a petition via the portal to amend the bill to include political parties and their foundations, unions, and the Royal House within mandated bodies under the RTI regime. This was later debated in Congress and public pressure was key to the inclusion of these entities as mandated bodies, against the preferences expressed by the Government and the President of the Court of Auditors (El Confidencial 2015).

However, after the enactment of the RTI legislation the website faced new challenges. From January 2015, Tu derecho a saber defied legislation and manually processed requests to the official Transparency Portal from requesters without proper ID, or from those who wanted their questions and answers publicly disclosed. The website goal to process online requests was getting more difficult to achieve, as both the central government and the local regions were adopting their own systems rather than sending their answers via email. Paradoxically, when Spain enacted a RTI legislation requesting information became more difficult. Due to these challenges and because they could not afford to continue requesting information, Access Info and Civio announced that they were closing down the website (Access Info- Europe 2015).

Within three years, the portal processed more than 1,800 requests. After the enactment of the RTI law in Spain (2015), Tu Derecho a Saber contributed to uncovering some of the weaknesses of the legislation and the lack of responses from mandated agencies.

3.5 Uruguay: What You Know (Quesabes.uy)

Background

The long process towards a Uruguayan RTI law started in 2002, during public and parliamentary discussions of human rights violations during the military dictatorship (1973-1985). The RTI law was finally enacted in 2008. The Uruguayan law is progressive (Centre for Law and Democracy and Access Info-Europe 2015) as it includes the whole of the public sector and a public interest test. Further, it allows individual requests for any kind of information, the only requisite for which is to have a written request following basic specifications. However, the law does not set an independent oversight public body. As a result, the implementation of the RTI law – eight years after its enactment – shows challenges in terms of proactive transparency, request procedures and resolution for conflicts (Scrollini 2015). One of the main challenges in the early days of RTI was to make citizens aware of the law. Another challenge was to simplify request mechanisms so requesters could ask for information in an efficient and simple way.

In 2012, DATA Uruguay, an open data and civic tech-oriented organisation, developed Quesabes (What You Know), a website based on Alaveteli that aimed to help users make RTI requests to government agencies. The website was launched with the support of a local RTI-oriented organisation, CAINFO Uruguay. The main objective of the website was to democratise access, allowing users to make RTI requests through email. It was conceived as an awareness and service delivery tool and was designed to test whether the Uruguayan government would reply to RTI requests through email. The whole project was done on a voluntary basis.

The portal initially included 80 public sector agencies and slowly increased the number of departments available, based on users’ feedback. DATA Uruguay used an online authority’s guide provided by the National Civil Service Office, which was in a closed data format, to find the email addresses for each public agency. The portal received wide media coverage and established DATA’s reputation in Uruguay. The national innovation agency, ANII, awarded DATA an honorary mention in its annual challenge in 2013.

Reactions

Quesabes received mixed responses from government. The oversight RTI agency, Access to Public Information Unit (UAIP),d2a438b8b837 and the e-government agency did not oppose the portal and even mildly encouraged it. The local Council of Montevideo initially resisted the idea of replying through the website, but eventually began to use the portal to reply to requests. The Parliament, however, notified users that they would only reply if users visited their office in person and filled out their form. Other departments did not reply to emails.

Quesabes received mixed responses from users. Some users eagerly used the portal to submit RTI requests and make comments to help other users. DATA, with the support of local RTI organisation CAINFO, actively lobbied public institutions to join the portal. Some institutions declined to reply, as it was not an official portal. DATA aimed to engage volunteers to run the website, but due to the lack of resources this did not happen.

In 2016, Quesabes registered 621 users and processed 434 requests. According to the user rating, 23% of the requests were considered successful or partially successful, while 15.6% of the requests were denied. About 44% of requests were ignored or an appropriate response was not provided. The rest of the requests were classified under a set of miscellaneous categories.ace5877b0898 Quesabes results are similar to other studies carried out by local researchers (Pineiro and Rossell 2015). Whether received by email or offline mechanisms, the most common response by the Uruguayan public agencies has been to ignore information requests.

Quesabes influenced the Uruguayan RTI regime in a number of different ways. It increased awareness of RTI in Uruguay and improved policy, as well as service delivery. Through media exposure and the sustained effort of DATA, Quesabes increased awareness of RTI. Quesabes has featured in 50 press articles at a national and international level since its launch. Furthermore, it informed more than 50 public administration departments about RTI through the portal and the advocacy of DATA and Cainfo. Currently, 25% of the Uruguayan population is aware of the RTI (Del Piazzo 2013).

The portal sparked a debate about the validity of email as a channel to submit RTI requests. The debate concluded that email was a valid way of exercising the RTI. Nevertheless, due to the limited enforcement capacity of the regulator, this is often not the case. Currently, the Uruguayan government is committed to a full legal reform to specifically include emails as a valid way of communication.

The portal remains the only centralised tool that allows users to exercise RTI online. It is also the only place where statistics about the use of RTI are available, as the Uruguayan government does not gather these records. Arguably, the portal had a performative function showing that it was possible to create this tool, and nudged the Uruguayan government to develop its own. To date, the national RTI portal is in beta mode, with only one organisation answering requests through it.

4. Analysis: What kind of effect do these portals have on Right to Information regimes?

In this section, we focus on the demand and supply sides of public information to better understand the effects of these portals over RTI regimes. We observe requesters and civil society organisations behind these portals (demand) and analyse the behaviours of the actors on the supply side of information, public agencies and RTI oversight institutions.

4.1. Demand side

We have observed seven effects over the demand side of public information. First, in all our cases the portals gave rise to one particular kind of actor: a civic tech organisation or individual. In Spain, Uruguay and New Zealand, the portal helped organisations that were relatively new or unknown become key players in the RTI regime. In the cases of Chile and Germany, the portal contributed significantly to the work and trajectory that organisations in these countries had before these projects. By developing and organising these projects, all the organisations and individuals involved gained recognition as key stakeholders of the RTI regime.

Second, in all selected cases the portals paved the way for a new type of digital activism and digital service. The construction of such a portal should be considered a radical act of digital activism as the action is designed to solve a public problem based on open tools and is carried out by self-organised citizens. This act operates at the border of traditional civil society activism, ethical hacking and government reformers communities. The development and organisation of a portal, without consent of a government agency contributed, in most cases, to the development of an official portal. More importantly, these portals embedded a set of values in their code about how the process for submitting a request could be designed to reflect citizens’ priorities; this performative effect should not be understated.

Third, just three of these projects have survived and continue without a stable source of funding: New Zealand, Germany and Uruguay. If these projects did not exist, there would be no digital channel through which to make RTI requests. Although these projects survived without donors and funders, the role of external funding should not be underestimated. With external support, these portals would probably achieve greater results at a lower cost for individuals and small organisations. Moreover, with the support of funders these portals could have produced similar effects in other RTI regimes.

Fourth, as a result of the activity and press exposure all these projects contributed to raise awareness about RTI. Through ‘leading cases’ (most notably in Spain and Germany) these projects contributed to raising specific issues in the media. Thus, these portals contributed to the work of advocates in this field.

Fifth, there is the matter of access. Due to poor record keeping and the lack of official statistics about RTI requests (except in the Chilean case), it is difficult to estimate if and how these portals have increased the overall exercise of the right to access government-held information by groups that are not usually engaged. It is likely that these portals contribute to increased access to particular groups of users; however, those groups are likely to be very similar to average RTI users. According to the available data about RTI users, most of them have a high degree of education (see, for instance, the case of Chile) however; there is a lack of comparative study in terms of RTI users in different settings.

Sixth, these portals contributed to the interaction between civic technologist and more traditional transparency-oriented RTI organisations. These developments contributed to discussions and established common points to pursue advocacy goals and promote RTI. Whilst the coordination of these activities is far from perfect (Fumega 2015), these projects provide motivation to these communities to start a more fluid dialogue.

Finally, all these projects operate in different civil society settings and require a careful contextual analysis to understand how portals interplay with larger issues and organisations. Due to the limitations of this work, we are unable to delve into this matter. We note that funding is less relevant in these cases, except for the Chilean case. All the portals were developed through voluntary efforts and supported by civil society organisations or private citizens initially through crowd-funding. However, as previously mentioned, the role of funders should not be underestimated.

4.2 Not all public administrations are the same

Public administrations are fragmented entities and communication between organisations can be a problem. This fragmentation has a twofold effect. In all cases it was possible to find sympathetic public organisations willing to answer requests, even without a specific mandate to do so. However, even with a mandate to reply, organisations in a public administration might not be willing to do so and may ignore requests to reply or even executive orders. Nevertheless, finding examples of organisations within a given public administration, and getting those replies is already a significant behavioural change. In order to reply to an email through an ‘unofficial portal’ it is likely that public servants obtained clearance from managers and politicians in charge of answering emails.

Public administrations have certain administrative and legal traditions that may favour (or not) engagement with these portals. Certain public administrations also have more capacity to engage than others do.In the New Zealand, for example, there was only one organisation not willing to answer through the portal due to the strong RTI tradition. This was not the case in Uruguay, Chile, Germany or Spain, probably due to the legal background of these public administrations or the so-called ‘administrative silence’. In the Uruguayan and Chilean cases, some organisations might not have the basic capacities in place to engage with these portals, especially during the early days. Note that even when there is a strong RTI tradition (NZ) or good state capacity (Germany), some organisations might still resist replying through an unofficial portal or via email.

4.3 Role of enforcement institutions: Friend or foe?

Depending on the RTI regime, oversight institutions can play a more or a less prominent role. While it seems intuitive that these institutions should welcome developments, this is not necessarily always the case. Some institutions decided to ignore the portals (Germany and Spain), while in Chile and Uruguay there were different degrees of collaboration. However, in New Zealand there was an explicit acknowledgement of the portal by the Ombudsman.

In a case where the RTI oversight institution presents some features that support these developments, then the oversight body could evolve as an ally of civil society actors behind the RTI portal. This was the case in the Uruguayan RTI regime where the regulator issued a directive indicating that email requests were a valid channel of communication and thus, they should be answered. In the Chilean case, the oversight institution cooperated in the initial promotion of the portal and built on FCI experiences when developing their own portal. These reactions add legitimacy to the work of these NGOs and could re-assert the authority and influence these institutions have in this field. Furthermore, these portals also could contribute to visibility of the institutions and their capacity to oversee the enforcement of the RTI legislation.

Nevertheless, in the Uruguayan, Chilean and Spanish cases, RTI oversight institutions developed their own official portal after the emergence of civil society portals. This represents an important behavioural change, as there were no plans to develop such portals until civil society portals were in place and performing as a de facto portal. In most cases, these official portals were not developed in partnership with civil society actors but in some cases, the NGO was asked to share their experiences of establishing a portal.

A lack of collaboration between NGOs and governments in developing official portals often results in a shift away from the citizen-oriented logic that was embedded in the initial civil society-led portals. This is clearly demonstrated in the Spanish case, where the portal ultimately shut down because there were serious difficulties in submitting requests as a result of the registration policy.6436e899c472 Registration policy is likely to become an issue in the Uruguayan case as well. It is not clear if, and how, NGOs are able to influence these processes. However, it is clear that their work contributed to opening up a previously untapped market for a particular aspect of government ICTs. While it is clear that these innovations affect the implementation of technological tools in a RTI regime, official portals are yet to fully incorporate citizen or civil society experience in their design.

5. Final remarks: What role for civil society lead portals in the digital age?

In this paper, we reviewed the experience of five civil society portals in developing and developed countries with different RTI regimes. We argued that civil society-led portals affected these RTI regimes in a positive way. In short, without the development of these portals, some of the positive changes in these RTI regimes would either not have materialised or would have developed later. In the following paragraphs, we provide a set of conclusions and recommendations to enhance positive outcomes, and present new lines of research in this field.

- Civil society portals affect RTI regimes in different ways. In best-case scenarios, the portals positively influence the way public administration and RTI oversight institutions function, as in Chile and Uruguay. In worst-case scenarios, the portals document, beyond doubt and in real time, the difficulties requesters face, as in the Spanish case. The portals were pioneers in providing users a simple way to request information online. Furthermore, they included positive features that were later not included in official portals. Proactive disclosure of all responses was an important feature that should be included in all future cases. It means that when there is a request for information, it should be further understood as a request to make that information public.

- The portals in the selected cases enabled a new type of civil society actor. Thus, donors and other supporters might consider supporting these projects to develop a new generation of NGOs. Funding has not been a determinant factor for the success of these projects and four of the selected five cases did not have any support from international donors, the three cases that remain active did not have any support. Local ownership by local actors is a way to sustain these efforts beyond funding. With more resources, these projects could have delivered increased behavioural change and continued to contribute to each RTI regime by engaging in activities that are mostly non-tech related, such as reaching out to the public sector, educating requesters and engaging in campaigning activities. Donors and civil society advocates need to consider the kind of regime they are engaging with and the objectives they are pursuing in these regimes in the design and decision to support these projects.

- It is necessary to develop a more detailed hypothesis (or “theory of change”) for these portals as the portals are not an immediate game changer in any RTI regime. It is not possible to support the techno-utopian visions about the tools that were eagerly celebrated in the optimistic first years of the civic tech movement. The initiatives all faced different institutional constraints, most notably the nature of the public administration and the role oversight institutions play. These initiatives act like a trigger in RTI regimes unchaining a set of (generally) beneficial effects for the regime. To date, there is no developed theory of change and it requires further research, particularly if researchers and practitioners face these studies in partnership. Such a theory would need to identify key metrics, but also should include qualitative aspects. Some of the changes the portals have already helped to bring included changes in the legal and institutional system.

- Each case demonstrates an innovative use of technology, but innovation does not directly translate to an improvement of digital public services. It seems that governments or RTI oversight institutions mirror civil society behaviour to develop their own portals. However, good practices implemented by civil society are not always adopted in official portals or portals. This begs for analysis on whether it makes sense to maintain civil society portals while there is also an official portal. We do not have a clear answer for this. Nevertheless, if official portals do not deliver a good service or are restrictive, then there is a case for the continuation of these portals and the addition of innovative features. Forums, such as the Open Government Partnership, might be good spaces through which to foster dialogue, but ultimately governments need reliable providers to run these services and might not be willing to incorporate all civil society suggestions.

- A better understanding of the impact of these portals on the way RTI delivers transparency and accountability is needed. These developments are part of a larger debate about the role of RTI in delivering accountability (see, for instance, Fox 2007; Hazell, Worthy and Glover 2010). Technology is just one important variable in a RTI regime, and portals are part of this landscape. Further, this is a very particular kind of technological development in a RTI regime. Concurring with Bailur and Longley (2014), developing and implementing a portal (in particular an open source, civil society one) is a radical act. To further explore the value of these portals, we might need to understand more about their specific advantages over government portals or other ways of requesting information. To judge success (or lack of success) of a project, it is important to understand the objectives these portals establish at the beginning of their design. In all the selected case studies, portals were developed with the aim of changing a given RTI regime. This overarching goal was, to varying degrees of success, achieved and the level of success depended on the resources and status of the RTI regime.

There are currently more than 100 countries with a RTI law. Thus, there is potential to spread these portals further and, in particular, there is space to re-think the way these projects can be implemented at a local level. Actors need to clearly articulate the kind of changes they will pursue in the short, medium and long run. Institutions are likely to resist, but with a good strategic focus, these portal might well improve the RTI regime.

- It could be added that in many cases it was run on volunteer basis. Through this paper we use the term free and open source software meaning software that can be inspected and is licensed to foster re-use. We understand that philosophically and practically they are not exactly the same.

- Currently there are several government portals allowing citizens to exercise their right to information. In this study, we do not cover such portals, and we focus only in the ones developed by civil society.

- A previous version of this article was published at proceedings of the 18th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research.

- As named by Darch and Underwood (2010. p.47)

- The Kingdom of Sweden was the first country to enact a regulation covering the access to public information back in 1766.

- Note that his assertion does not mean that public services are becoming more inclusive as a result of digitalization. It means that increasingly public services are going “digital” by default.

- Alaveteli is a type of software available to civil society to build portals to fill-in RTI requests.

- A list of FOIA technologies available have been compiled by 18F available at https://github.com/18F/foia/wiki/Portals

- Open source means that the software is available with little or no-restriction to inspect, copy or redistribute. Further, it implies a collaborative development model where several actors can contribute to the development of the code. This model promotes rapid software development.

- With regard to the disclosure of responses given to the requesters, in Mexico, both the requests and the responses can be accessed on the INAI (National Transparency Institute) portal. Through this portal, a user can access information that was previously requested -and for which a satisfactory response has been given- without having to re-file the same request. There is a rationale behind publishing this information: the INAI understands that when information is requested, it is not just for an individual to access a particular piece of information, but rather a request for that information to be made public; this is why both the requests and the responses are regarded as public. In Chile, on the other hand, the portal of the Council for Transparency only allows the request and the response to be seen by the user who filed it. This is because the portal’s information system cannot differentiate which parts of the request and the response should be classified as private or sensitive information, and which should be public. Therefore, responsibility is entrusted to the agency involved (Fumega 2014).

- The cases of Chile, Germany and Uruguay were previously explored in a preliminary working paper presented at the Global FOI Conference (Los Angeles, November 2016). This paper was developed by Silvana Fumega, Fabrizio Scrollini and Arne Semsrott. (Fumega, Scrollini and Semsrott 2016).

- For example, Hamburg introduced its Transparency Law that mandates authorities not only to disclose most of its data reactively, but also proactively. Contracts with private actors have to be published a month before they come into effect, giving the public the option of vetoing it beforehand.

- Relevant in a country with more than 60 different RTI regulations at the local level and which establish different exemptions, fees and deadlines. Portal users do not need to know about the particular legal provisions and do not need to cite it when filing a request.

- The Access to Public Information Unit (UAIP) was created by article 19 of Law 18,381 on Access to Public Information as a decentralised body of AGESIC, the Uruguayan E-Government Agency dependent of the Executive

- This information emerges from quesabes.uy admin data. Other categories included: unsatisfactory reply, answer via postal mail and withdrawal of the request. However, these constituted only a small percentage.

- Note the Spanish website is not owned by the RTI oversight institution, but by the Spanish Government