The importance of a satisfactory audit

Numerous corporate (eg Enron, Parmalat) and public sector (eg Carillion) collapses renew the widely reported dissatisfaction with auditors’ reports: specifically, that they did not provide the client with the information needed to know the risks and make decisions. A clean report does not mean that waste or fraud did not occur; nor does it ensure high-quality outcomes. An expectation gap remains between the auditor and the funder, and with the voting, taxed, or donating public. The need to specify the purpose of an audit extends to the development sector as well as the corporate sector. Clarity between the auditor and the readers of their report is essential, and this must be achieved before the audit starts.

Auditing standards bind the auditors’ profession in their work and client obligations. For example, ISA 240 refers to misstatement due to fraud and identifying the danger of misrepresenting the financial statements or undermining reported non-financial conclusions. The standards also require the auditor to understand their client’s use of the report and the phrases they expect to see in it. The profession relies on its members to prepare teams with relevant skills and experience to meet the assignment’s objectives and for review and quality assurance to be crucial parts of it.

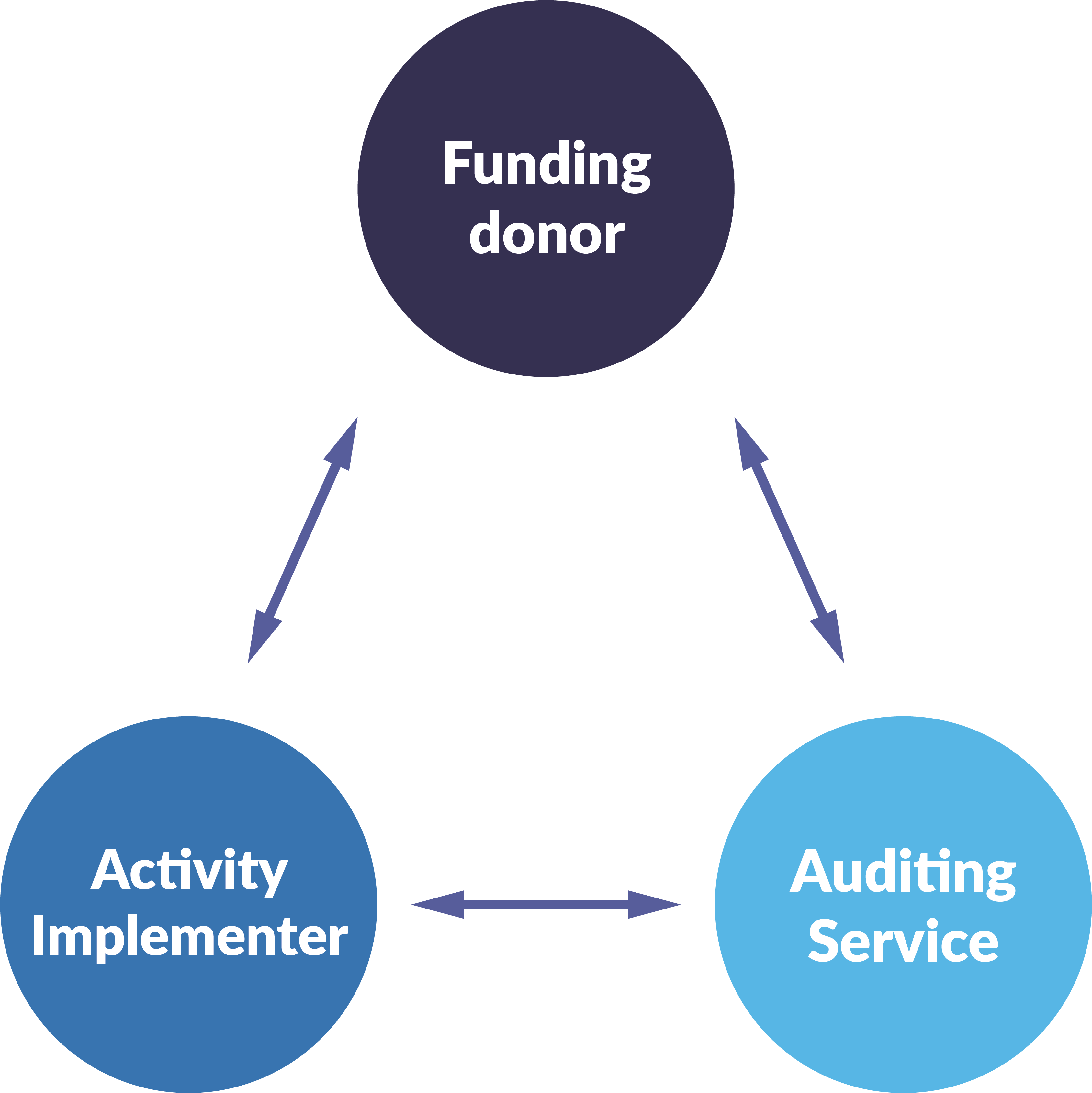

A good audit brings independent and professional insight for both the funder and the auditee, and should focus on the decisions influenced by the report. This can be reflected in the terms of reference issued to the auditor, which can be unique to the funder. The triangle of the funder requesting the audit, the party being audited, and the auditor needs to involve more dialogue and clarity on purpose, identification of risks, and understanding the decisions that will be made based on the findings.

Establishing an effective audit triangle

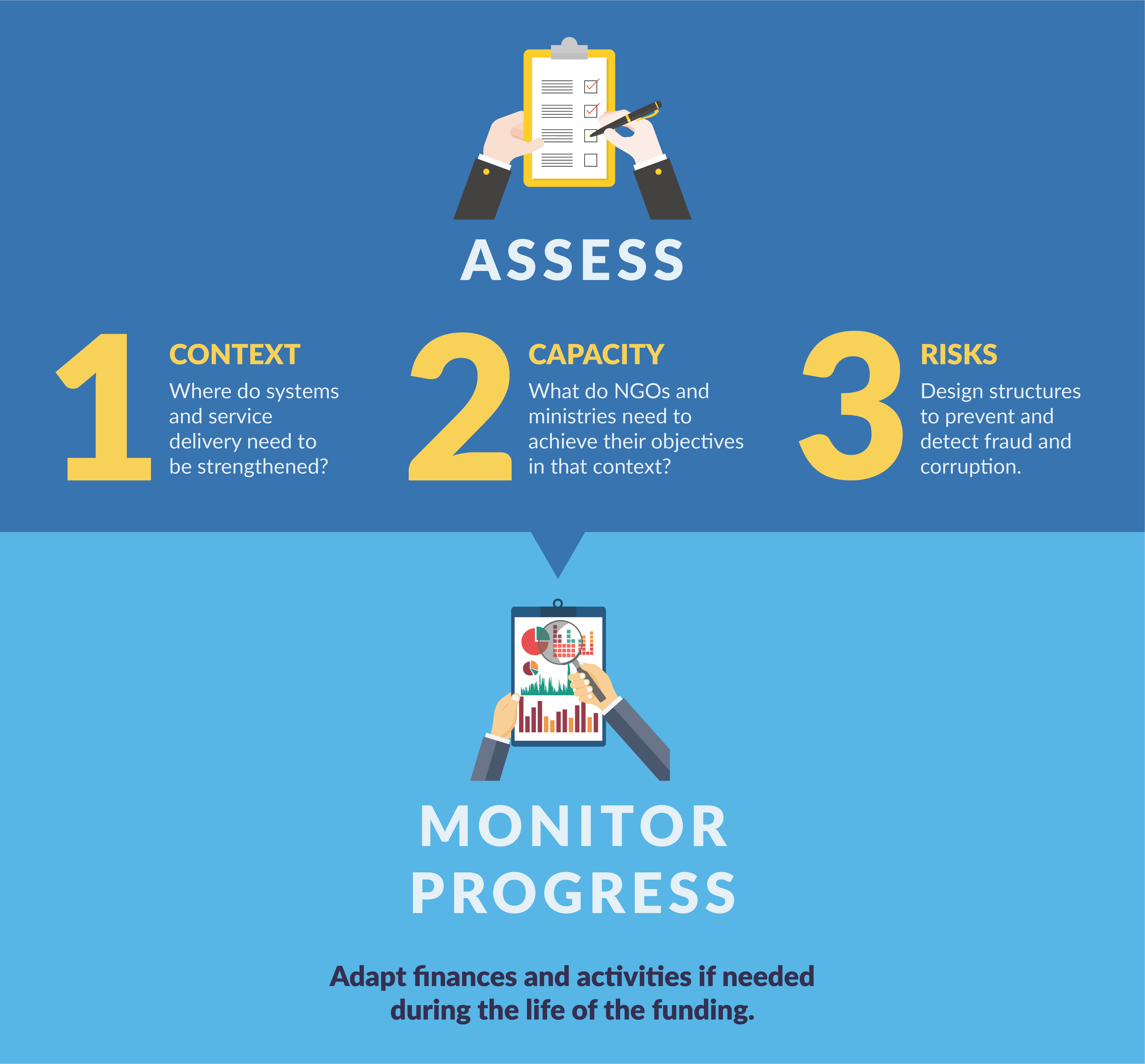

The effective delivery of development – whether strengthened systems or changing the circumstances of the population as measured by key indicators – requires a context-based management plan and active monitoring during implementation. It is vital to identify the threats to success, the risks of aid diversion, and the markers of good progress. Threats include fraud or corruption, weak management, or poor programme design and quality control. Planning is more important in the development or humanitarian sectors than the corporate sector. The location and choice of implementing partners is not as open and commercially risk based as manufacturing or retail environments. Confirmation that a payment voucher has been documented is not a suitable assessment of complete service delivery, quality of training, or effectiveness of behaviour change campaigns.

Audits, as a mechanism to ensure ‘good’ has occurred and ‘bad’ was mitigated or minimalised, need to be risk focused. This is not a new concept to auditors – planning assignments, selecting staff, and testing a statement or figure should all be risk based. Auditing standards refer not to the format of a report but to the professionalism of the audit team and their understanding of client and context. Financial corporate accounting and ‘standard’ corporate audits focus on the true and fair view of the presentation of the report and its narrative; whilst a ‘donor audit’ is as varied as the priorities of those commissioning it.

This U4 Brief considers the three parties of the audit triangle in relation to the existing International Auditing Standards, and suggests how team composition, better contextual understanding of risks, and clarity on decision making can combine to promote greater assurance. Audits will be more effective, and worth the disruption they could cause and the expense invested in them.

Identifying what is important to the sponsor who requests the audit

The sponsor (eg the funding donor) seeks assurance on implementation of their plans and the performance of those safeguarding their funds and reputation. This can include commentary on how effectively managers of the funded entity are acting on specific issues, such as minimising fraud and corruption or increasing engagement with local entrepreneurs.

The sponsor directs the implementers and the reviewers to operate in ways that could achieve some aspects of the outcomes they have defined. However, there is a danger of over-emphasising the issues that most interest them – office-based verification of transactions, to prevent fraud. Pre-occupation with adherence to documented procedures as the main tool for fraud prevention can lead to blind spots as to whether the programme is achieving its intended aims.

Over-emphasis on one aspect can harm another aspect of the programme, or delay implementation. For example, focusing on receipts for hotels and travel claims for a training event gives minimal assurance that the participants attended the whole training, learned anything from it, or could use it to improve their work. However, an auditor testing these outcomes could provide more assurance than checking just financial receipts. Audits that include outcomes and effects are referred to as Performance Audits but are still a form of an assignment with Agreed-Upon Procedures.

Some providers of development grants already invest in fiscal agents to oversee the financial operations of grantees in real time, or appoint finance-oriented interim reviewers of reports and supporting documents (eg the Local Fund Agents (LFAs) of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria). Real-time finance support has recently been given an expanded role to link programme activity, management, and performance to accounting support, or include risk assessments and fraud mitigation in their tasks.

Similarly, as the Global Fund’s LFA model evolved, teams changed from accountants or auditors to monitoring and evaluation specialists and public health programme experts. This has allowed a partial change in the finance-only approach of donors towards grant audits and significantly improved their ability to obtain programmatic assurance. It also aligned reporting requirements among funders, which eased the administrative burden on non-profit organisations with multiple national and international funding sources.

A mature, practical assessment of key threats to outcomes and impact is necessary at the design stage, and during the project’s management. Local and national knowledge of the context – including fraud or corruption risks – affects the success of the development plans. This allows the donor to understand the skills required by an audit team, which can be included in their instructions or team selection criteria.

Minimising threats to successful implementation

The audited party has a significant role in changing the nature of audits and improving the collaboration and trust between funder and implementer. An implementing organisation should be aware that when it receives money to deliver a development outcome, there is a potential risk that the funder does not clearly define how it will determine the quality and completeness of the delivered services (and what the auditor will look for). This could place the implementer in an awkward position when reports are due, or when the audit begins.

Development grant recipients should not avoid or delay the audit discussion as it could lead to undesirable consequences, such as extra work to achieve reporting requirements, financial hardship from disbursement delays, and denials of refunding due to lack of evidence of achieved outcomes. It is frustrating for funders and implementers when the evidence for assurance is meaningless in the country of implementation. For instance, receipts for small-value sales are worthless as audit evidence of a transaction taking place; the requirement to obtain three quotes for procurements does not assure value for money was achieved or a cartel was not involved in making all the offers; and a receipt for petrol does not guarantee the journey was made for project purposes.

To promote the quality of evidence of impact, organisations using donor funds should engage the donor and propose that they are judged on proof of outputs or short-term outcomes instead of over-relying on accounting entries. Such proof is often included in the technical programme management.

An audit concentrated on outputs and outcomes becomes both an efficiency monitor and a process-improvement tool. An auditee’s staff and managers are more likely to welcome a supportive audit than one that appears to be designed to catch them out.

Funders and implementers can ensure improved audits, which minimise wasted time checking payment vouchers and lengthy procedures, by sharing information at the start of the relationship that covers:

- Reputational and other risks of concern to the funder (eg anti-money laundering)

- Diversion and inefficiency risks that exist in the country of operation

- Weak documentation risks in the planned activities

- Reporting risk of placing inappropriate reliance on the wrong information

Before the partnership begins, a donor should ask an implementer how these risks will be identified and mitigated to a suitable level. This defines a section of the terms of reference that is usually missing in a purely financial audit: ‘Provide a report on the extent to which the planned mitigation actions were evidenced as occurring as agreed in the partnership agreement.’

Planning the audit and team composition

The auditor can work in two ways:

- Evaluating a management system of procedures and controls to determine its effectiveness, whilst considering the tasks to be achieved, context, staff, and time frame

- Reviewing documents and making enquiries after the event to establish whether procedures and controls did operate, including detailed testing of a sample of events or payments

The awareness of the audit team of the context where development projects are being delivered significantly affects the strength of the audit work. An audit that relies too much on documentation and explanations may not involve the professional scepticism expected of an auditor. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners annual report also guides donors and auditors on what to focus on to safeguard funds and ensure programmes achieve their goals: collusion, management override, or corruption. Also auditors should consider the political, social, and economic contexts, and the norms and attitudes towards corruption.

The auditing standards make clear the auditor’s responsibility to plan their work, understand the client and setting, and to provide an opinion or report on agreed tasks. This includes employing sufficient staff, committing enough time, and ensuring the team has appropriate skills and effective supervisors to fulfil the scope.

In the corporate setting, local accounting standards or international financial reporting standards guide finance directors and financial auditors. The preparation of financial statements is the clear responsibility of the entity being audited, but the auditor refers to these standards when checking how to present a transaction and how to group them by accounting period, and when providing guidance on valuation and recognition of assets and liabilities. A recent initiative, #IFR4NPO from The Chartered Institute of Public Finance & Accountancy (CIPFA) and Humentum, is developing an internationally recognised financial reporting standard for the non-profit sector. This would be of benefit where finance-only audits persist, as it would clarify the preparation of reports and what reliance can be placed on their presentation and the audit opinion.

The design and management of a development programme has much broader considerations than the presentation of the financial statements of spending during the period. The expected skills of the audit staff and their scope of work must be reflected through Agreed-Upon Procedures that the auditor will perform to provide the level of assurance agreed in the Letter of Engagement. Such a ‘compare and comment’ role draws on the programmatic and contextual experience of the audit team and their managers to plan their analytical review processes appropriately. This means that an auditor considers what could go wrong, what controls should be effective, and what telltale actions could imply loss, fraud, or corruption that could affect the accuracy of the report they need to provide. However, this provision should not be misunderstood as an instruction to identify all fraud or acts of corruption or inefficiency.

The European Commission issued new guidance in August 2018 to clarify expenditure verification assignments, and separately on financial and systems audits, which changed their broad approach of auditing a proportion by value of all spending to a more risk-based one. The new reports require auditors to record the link between identified risks and the selected sample, and which of the tested transactions presented findings and which did not. This information, available in electronic format for EU-funded projects, will simplify the reconciliation between reported amounts and the amounts recorded in accounting systems.

Strengthening the relationship between funder, implementer, and auditor

Funding and programme managers need to align their approach to planning, achieving, and demonstrating effective use of development funding. However, improving the way audits are done will require better use of the staff time and costs already invested in reviewing proposals and appointing auditors. The way forward is to embed into the programme’s design, monitoring and evaluation, and indeed its audit, thorough understanding of the corruption and fraud risks that could prevent the desired development goals. This requires that audit will no longer just be conducted to assess whether funds have been spent well, but that grantees will be assessed before the grant award is confirmed.

The funder must perform the groundwork by:

- Fully understanding the need for systems strengthening or service delivery and how that should be achieved

- Considering the implementation challenges – logistical, behavioural, social, cultural – and the necessary skills and experience

- Identifying programme management structures to mitigate those risks, including preventing and detecting fraud or corruption

- Actively managing the implementation, and cross-referencing outputs to activities, workplans to spending plans, and actual pace of change to staff activity and expenditure levels

The audit and assurance provider can contribute to the first of these steps, and then deliver interim assurance on the operation of the management processes. The after-the-event review can then determine whether the controls did operate, provide recommendations for the next period of operation, and check the past period’s reported outputs, outcomes, and effects regarding the funds utilised and documentation provided.

The provider (whether qualified auditors or experienced verification teams) needs to be multi-skilled to appreciate the breadth of issues that contribute to successful design and delivery, management, and reporting in the relevant sector. Therefore, audit and verification teams will have to be multi-disciplinary, with local experts or specialists in the sector under review, as well as fraud specialists.

Audits and the assurance framework should be comprehensive – evaluating systemic soundness of financial and programme management systems before, during, and after – rather than simply exercises to check for fraud or reconcile invoices. This requires terms of reference that reflect a risk-based approach. Audits will be more satisfactory when better alignment is achieved between implementers and sponsors on the desired project goals, the risks, and the definition of quality. The audit will be a more reliable oversight tool for the funder. Also it will assure the implementer and the intended beneficiaries that the intervention was well designed, effectively managed, and that the controls and monitoring focused on relevant measures and milestones.

Development actors should consider interim assessments, especially with new programmes or new implementers, to catch issues early. This ‘rolling audit’ type of approach ensures that implementers continuously improve their systems to identify and manage risks, subsequently ensuring the success of development programmes.