Query

Please provide an overview of corruption and anti-corruption efforts in Kazakhstan.

Background

Kazakhstan grapples with endemic graft, restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, and parliamentary and presidential elections that are neither free nor fair (Freedom House 2023).

Since declaring independence from the Soviet Union in December 1991, Kazakhstan has had only two presidents. Nursultan Nazarbayev governed for nearly 30 years until he resigned in March 2019 (Eurasianet 2019). His hand-picked successor and then senate chair, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, assumed the role of acting president, but in April of the same year, he announced snap elections to avoid “political uncertainty” (Eurasianet 2019).

Tokayev won the 2019 election and secured re-election in 2022 (Al Jazeera 2022). International observers highlighted “clear violations of fundamental freedoms as well as pressure on critical voices” in the 2019 presidential elections (OSCE 2019). Similarly, they noted that the 2022 elections were held in a political environment lacking competitiveness, with significant constraints on the ability of citizens to participate in political life (OSCE 2022).

Despite his resignation, Nazarbayev initially retained a firm hold on power, maintaining roles as the first president of the Republic of Kazakhstan-Elbasy, chairman of the security council, and leader of the ruling Nur Otan party (Freedom House 2022).

However, in late 2021, Nazarbayev stepped down from the leadership of the Nur Otan party and transferred it to Tokayev (Putz 2021). Subsequent changes unfolded after unrest in January 2022 sparked by an increase in fuel prices but fuelled by widespread discontent over inequality and corruption (Transparency International 2023a). The protests resulted in over 200 deaths (Transparency International 2023a). Protestors particularly highlighted the allegedly ill-gotten wealth of the family of former president Nazarbayev (Sauer 2022; Transparency International 2023a).

In response, Tokayev initiated several anti-corruption reforms. These reforms encompassed efforts to recover stolen assets from abroad, advancements in digitalisation to facilitate the monitoring of public spending, amendments to legislation mandating public officials to submit income and property declarations, a ban on gifts to civil servants and using funds seized from corrupt public officials for public infrastructure projects, among other measures (Yergaliyeva 2020; Kazinform 2022; Tastanova 2023; E government 2023).

While some of these reforms have produced results, such as the recovery of illegally obtained assets reportedly amounting to US$1.7 billion (Kumenov 2023), whether enforcement efforts will be sustained and prove to be even-handed remains to be seen. Some observers have noted the anti-corruption crackdown initially appeared to be concentrated on the inner circle of former president Nazarbayev, targeting, for example, his family members, associates (Eurasianet 2022; Lillis 2022a, 2022b; Sochnev and Rickleton 2022; Kumenov 2022, 2023).

Extent of corruption

While the government has formally prioritised the fight against corruption for over a decade, corruption remains widespread (BTI 2022; GRECO 2022b). International and domestic observers, as well as civil society organisations, offer a mixed assessment of the trajectory of corruption levels in Kazakhstan.

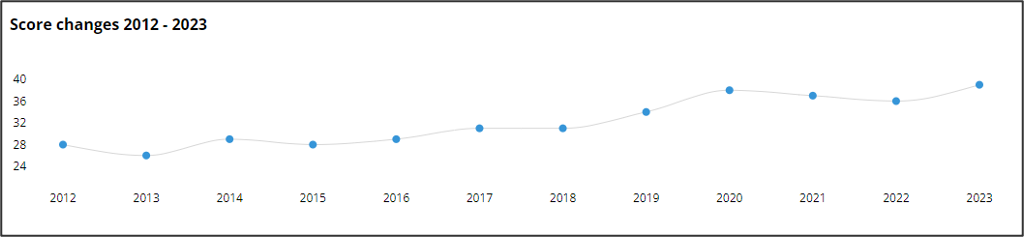

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for 2023, Kazakhstan scored 39/100, ranking 93 out of 180 countries. Kazakhstan’s CPI score was gradually improving between 2015 and 2020,before dropping in 2021 and 2022 and improving again in 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CPI score for Kazakhstan (2012-2023). Source: Transparency International 2024.

Freedom House’s (2022) Freedom in the World Index categorises Kazakhstan as “not free”. Furthermore, Nations in Transit places Kazakhstan in the lowest category of consolidated authoritarian regimes (Freedom House 2023). The Freedom in the World report highlights that corruption in Kazakhstan is widespread across all government levels, and that corruption investigations into and prosecutions of high-level political and business actors are rare and typically target those that fall out of regime’s favour (Freedom House 2022).

Along the similar lines, the latest Bertelsman Transformation Index (BTI) (2022) report on Kazakhstan notes rampant levels of political corruption and nepotism, hindering efforts to optimise public spending, professionalise public administration, and eliminate wasteful managerial practices.

Other and more recent indices suggest gradual improvements in anti-corruption efforts. For example, the World Bank’s (2023) Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) for 2022 show Kazakhstan’s control of corruption score as -0.19,655125276794 the country’s best score in a decade (2012-2022), placing Kazakhstan in the 49th percentile (see Table 2). This indicator measures the strength of public governance based on perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain (including both petty and grand corruption), as well as the capture of the state by elites and private interests (World Bank no date).

Table 1 Kazakhstan’s scores on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) at 3-year intervals.

|

|

2016 |

2019 |

2022 |

|||

|

|

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

|

Voice and accountability |

-1.21 |

13.79 |

-1.23 |

14.49 |

-1.07 |

19.81 |

|

Political stability |

0.00 |

47.62 |

-0.17 |

41.51 |

-0.36 |

32.55 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-0.14 |

47.14 |

0.07 |

54.76 |

0.14 |

58.49 |

|

Regulatory quality |

-0.16 |

47.14 |

0.11 |

60.48 |

-0.01 |

52.83 |

|

Rule of law |

-0.51 |

32.38 |

-0.51 |

32.86 |

-0.47 |

35.85 |

|

Control of corruption |

-0.83 |

21.9 |

-0.29 |

45.24 |

-0.19 |

48.58 |

Source: World Bank 2023.

2019 survey evidence suggests improvements in the perceptions of corruption on the ground. For instance, a sociological survey on corruption experience conducted by Transparency International (TI) Kazakhstan (2019), which included individuals and representatives of small and medium-sized businesses, indicates that over half of respondents (54.4%) believe the number of corruption cases in their community likely decreased in the past year. Furthermore, only 13.4% of respondents and 9.2% of small and medium-sized business representatives answered that they encountered corruption upon contacting government agencies with a specific issue (TI Kazakhstan 2019). The same TI Kazakhstan (2019) study also found that most corruption cases occur in the state-run hospitals and clinics, police, land management authorities, state-run kindergartens and higher education institutions (TI Kazakhstan 2019).

The latest available Global Corruption Barometer data from 2016 suggested that 37% of respondents in Kazakhstan considered corruption to be one of the three main problems facing the country (Pring 2016: 8). In the same survey, 46% of respondents expressed the view that their government was performing “badly” in terms of at curbing corruption in government (Pring 2016: 13). The percentage of responding public service users who had paid a bribe in the previous 12 months was measured at 17% (Pring 2016).

Forms of corruption

While corruption takes various forms in Kazakhstan, three are particularly salient, due to their magnitude and reach into different institutions. Therefore, this section focuses on grand corruption, nepotism and administrative corruption.

Grand corruption

Complex network ties between politics and business have historically been used by the inner circle of the political regime in Kazakhstan to capture public funds and extract rents from state resources, including those from privatisation and state-owned companies.

In 2018, for example, former minister of economy Kuandyk Bishimbayev received a 10-year prison sentence for bribery and embezzlement. According to investigators, he embezzled approximately US$3.1 million from a US$130.6 million construction project, operating within a network of 23 people and two firms. This was accomplished by laundering payments disguised as intended for construction workers’ food and housing, redirecting them to Bishimbayev via his cousin (RFE/RL 2017; Putz 2018). Following the unrest in January 2022, a series of investigations were initiated against high-profile figures suspected of corruption that formed part of former president Nazarbayev’s inner circle. For example, Nazarbayev’s nephew, Kairat Satybaldy, whose roles spanned official government positions and private business, was sentenced to six years in prison in September 2023 for embezzling money from state-owned companies (Kumenov 2023). Specifically, with four others, he was found guilty of stealing more than US$58 million from the Transport Service Centre company and causing physical damage worth US$25 million to the telecommunications company Kazakhtelecom (Sayki 2022; Lillis 2022a). During the investigation, the Anti-Corruption Agency claimed that owners of railway companies connected with Satybaldy made multi-billion profits by unjustifiably raising road access prices at the expense of citizens (Sayki 2022; Lillis 2022a).

There are also allegations of grand corruption implicating former president Nazarbayev. One OCCRP investigation has uncovered that he reportedly controls assets worth billions of dollars through charitable foundations (OCCRP et al. 2022). Although Nazarbayev does not formally own them, as the founder, he exercises control over these foundations (OCCRP et al. 2022) and according to legal experts has the final say in matters related to selling or dispensing with the assets they own (OCCRP et al. 2022). OCCRP et al. (2022) state that there is a lack of transparency in the operation of these charitable foundations as they do not publish annual reports and some of their assets are hidden behind complex and secretive foreign commercial structures. Four private charitable foundations established by Nazarbayev in his time as president acquired stakes in dozens of businesses over the years. Some assets were transferred to these foundations by oligarchs who acquired wealth during Nazarbayev’s rule (OCCRP et al. 2022).

There is evidence that Nazarbayev’s circle also concealed beneficial ownership through complex networks of offshore companies to facilitate high-level corruption schemes. For instance, one case involving leaked offshore documents suggests that the unofficial third wife of Nursultan Nazarbayev, Assel Kurmanbayeva, received US$30 million through multiple transfers involving six offshore companies, with all except one registered in the British Virgin Islands (Patrucic et al. 2021).

Finally, leaked evidence of offshore dealings implicates not only former president Nazarbayev’s circle but also that of the current President Tokayev (Sorbello 2022) prior to his presidency. Specifically, it has been revealed that Tokayev’s son and wife established secretive offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands and acquired apartments around Lake Geneva and in Moscow, totalling approximately US$7.7 million (OCCRP and Vlast 2022). While neither the current president nor his wife had any known businesses, their son Timur was, among other businesses, listed as co-owner of an oil company that in the early 2000s was awarded lucrative development rights to a Kazakh oil field, enabling him to amass millions in profits by the age of just 18 (OCCRP and Vlast 2022).

Nepotism

In 2010, Orozobekova identified widespread nepotism in Kazakhstan, arguing it constituted one of the key obstacles to economic and political development (Orozobekova 2010). Deep patronage networks and nepotism, cultivated under Nazarbayev’s rule, allowed his close relatives to amass huge wealth in lucrative sectors like energy and banking, as well as in official government positions (Eckel and Alikhan 2020).

Several close relatives of Nursultan Nazarbayev are part of a network who own lavish real estate properties in the West (Eckel and Alikhan 2020). An investigation by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) revealed that Nazarbayev’s relatives spent at least US$785 million on real estate purchases in Europe and the US over a 20-year period (Eckel and Alikhan 2020).

In the UK, Unexplained Wealth Orders (UWO)a9f9afef5493 were launched in 2019 against Nazarbayev’s daughter Dariga and grandson Nurali Aliyev to oblige them to justify how they acquired £80 million worth of UK property (University of Exeter 2022). The British National Crime Agency (NCA) alleged that properties were bought with illicit funds tied to Dariga’s former husband Rakhat Aliyev (TI UK 2020). However, a UK high court dismissed the UWOs in April 2020 (TI UK 2020). A recent report commissioned by the Global Integrity Anti-Corruption Evidence Programme considers the judgement to be flawed, arguing that the judge accepted evidence provided by the Kazakh authorities that was likely unreliable, given Nazarbayev’s control of Kazakhstan at the time when the UWO was issued (University of Exeter 2022; Mayne and Heathershaw 2022). The Global Integrity report further notes that the NCA did not sufficiently focus on kleptocratic networks centred on the Nazarbayev family “that forms the basis of Kazakhstan’s political economy” (Mayne and Heathershaw 2022: 4).

Following the 2022 January unrest, the new regime began targeting nepotistic and patronage ties that developed during Nazarbayev’s administration. For instance, in January 2022, President Tokayev ordered the dismissal of Samat Abish, Nazarbayev’s nephew, who held the position of the first deputy head of the powerful national security committee (KNB) (Kumenov 2022a).

Nonetheless, other members of the Nazarbayev’s network reportedly continue to amass wealth. Shortly after the January 2022 protests, Nazarbayev’s son-in-law, Timur Kulibaev, resigned from the influential lobby group Atameken, where he had served as the head for eight years (France 24 2022). Despite this, he was reportedly able to increase his fortune in 2023 to an estimated US$4.3 billion (Kumenov 2023; Forbes 2023).

Administrative corruption

According to the 2016 Global Corruption Barometer survey, nearly one-third of respondents stated that they or their family members made an unofficial payment or gift when using public servicesfb70d1c73fd6 over the past 12 months (Pring 2016: 18). A more recent study by Transparency International Kazakhstan (2019) suggests that 56.3% of respondents believed that corruption was an integral part of daily life. Of those who had contacted government bodies over the past 12 months, 13.4% said they were forced to resolve the issue “informally”.

The Anti-Corruption Agency of Kazakhstan (2022:9) notes that the list of organisations and institutions vulnerable to corruption (which was identified via an analysis of the complaints from the Open Dialogue web platform) remains consistent from year to year, and includes state medical clinics and hospitals, the police, land relations departments, public service centres, state kindergartens and universities. The key structural drivers of corruption in these entities reportedly relate to administrative barriers, discretionary regulations and a lack of transparency in government bodies. Corruption vulnerabilities also affect revenue collection. Although entrepreneurs’ perceptions of bribe requests from tax officials are not exceedingly high, they are above the median levels of emerging countries (IMF 2022: 37).

Drivers of corruption in the public financial management cycle

Public financial management (PFM) refers to the set of laws, rules, systems and processes used to manage public funds effectively (Lawson 2015; see also Duri 2021; Duri et al. 2023). It incorporates revenue mobilisation, budget formulation, approval and implementation, public funds allocation, public spending, internal accounting and reporting, and external oversight (Lawson 2015; Duri et al. 2023). As such, a robust PFM is the key element of a functioning administration, essential for the provision of public services (Morgner and Chêne 2014; Duri 2021). When done properly, PFM ensures efficient revenue collection, as well as appropriate and sustainable use of public funds (Morgner and Chêne 2014; Kristensen et al. 2019; Duri 2021). However, the PFM cycle is vulnerable to forms of corruption, including grand corruption, nepotism and administrative corruption.

Evidence suggests that comprehensive PFM reforms can serve as an indirect anti-corruption intervention (Jenkins et al. 2020). This is because where the collection, allocation and expenditure of public resources can be clearly accounted for, this is likely to inhibit the volume of discretionary funds over which only limited oversight is exercised, which in turn, reduces the chance that these resources are misappropriated. Recent analysis of 99 countries by the ODI found that more robust PFM systems, as measured by PEFA indicators, are associated with lower perceived levels of corruption after other factors are controlled for (Long 2019). In the Kazakh context, President Tokayev has emphasised the need for public governance reforms to reduce vulnerabilities to corruption, including in the areas of public procurement, revenue administration, fiscal transparency and state-owned firms (in terms of oversight and privatisation) (IMF 2022). Earlier data has shown that financial violations and inefficient use of budget funds are substantial in Kazakhstan. For instance, according to the supreme audit chamber’s reports, between 2013 and 2016, the losses stemming from financial violations, including inefficient use of budget funds, reportedly amounted to US$6.9 billion (Shibutov et al. 2018: 41). This reached a peak in 2020 with recorded losses of US$4.6 billion (Kursiv 2021); this has sharply decreased decreased in recent years with annual losses for 2023 recorded at US$1.2 billion (Асхат 2024).

2018 estimates from the Anti-Corruption Agency suggest that annual corruption committed by public sector actors amounted to approximately US$3.8 billion, corresponding to 10% of the annual budget (Shibutov et al. 2018: 41). The majority of these violations occured in the implementation phase of state programmes (Shibutov et al. 2018: 41), which is the public spending phase of the PFM cycle when risks of embezzlement and bribery at the organisational level are most likely to occur.

In recent years, Kazakhstan has undergone several fiscal reforms, including revisions to the tax code, the introduction of a new budget code, the work on a new public procurement law and fiscal decentralisation, among others (IMF 2022). The IMF (2022) has highlighted some positive developments, such as increased digitalisation, which has reportedly helped reduce vulnerabilities to corruption. For instance, the introduction of e-invoicing has reduced opportunities for VAT fraud, while corruption risks have been decreased due to reduced face-to-face interaction between taxpayers and tax officials (IMF 2022: 38).

A lack of transparency and oversight in the budget allocation process

The anti-corruption policy concept for 2022-2026 in Kazakhstan identifies several important vulnerabilities to corruption in the PFM cycle (Anti-Corruption Agency 2022). One such priority relates to corruption risks associated with the budget allocation process. Limited transparency in the budget allocation and spending is one of the key systemic factors that increase corruption risks in the PFM cycle (Anti-Corruption Agency 2022: 10). According to the Anti-Corruption Agency (2022: 10), the key factor behind this negative practice is the inadequate connection between planning and spending of budgetary funds, considering that applications for budget allocations by line ministries are frequently based on unrealistically high bids from companies, which are often linked with public officials. This can result in embezzlement, favouritism in the allocation of budget funds and kickbacks in public contracting.

An IMF (2022) study notes additional vulnerabilities in Kazakhstan’s PFM cycle that may facilitate corruption. These include scattered fiscal responsibilities and ad-hoc decisions, stemming from the high number extra-budgetary funds and quasi-public entities that are not under the direct remit of the budget (IMF 2022: 30). While the number has been steadily decreasing in the past 10 years, there are currently around 7,000 quasi-government entities in Kazakhstan, primarily comprising state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and other public entities that offer government services on a non-commercial basis (IMF 2022: 31; Тонконог 2023). The majority of these entities are fully owned by the state, while less than a thousand are firms in which the Kazakh government holds shares (IMF 2022: 31). Most quasi-government entities fall under the ownership of two national holding companies: the sovereign wealth fund, Samruk-Kazyna, covering non-financial public corporations and which is mainly involved in the natural resource sector; and Baiterek, covering financial institutions (IMF 2022: 31-32). As of 2022, Samruk-Kazyna represents around 40% of Kazakhstan’s GDP, holding national oil and gas, energy, mining, industrial, transport and telecommunication assets valued at an estimated US$69 billion (SWF 2022; Samruk-Kazyna no date).

These quasi-public sector entities can contribute to a lack of robust PFM oversight. For instance, the Anti-Corruption Agency (2022) has found that by authorising an increase in capital of the quasi-public sector entities, state actors can effectively remove budgetary funds from the oversight system. Considering these challenges, a recent IMF (2022: 30) study suggests that reforms to the quasi-public sector should bring entities that do not operate on commercial principles under the supervision of corresponding line ministries.

Audit reports (Gov.Kz 2022: 19) indicate that the Samruk-Kazyna constitutes a significant PFM vulnerability as it is not subject to the same level of oversight as the state budget and there is no single government body responsible for the effective implementation of the funds. Evidence suggests national companies bypass the budget code and make transfers to the Samruk-Kazyna to increase the level of authorised capital in different sectors and finance projects (Gov.Kz 2022: 14). The auditor report found that projects financed from Samruk-Kazyna tend to incur higher costs than those financed from the national budget and estimated that 16.5% of Samruk-Kazyna transfers are misused (Gov.Kz 2022: 14, 31.).

Recently, certain ad-hoc public funds have been created as part of new policy initiatives, meaning they were not allocated through the formal budget process (IMF 2022: 32). For example, the public fund, Kazakhstan Halkyna, ostensibly receives donations from private structures to be spent on social issues (Kazzinc n.d.). Recently, the fund has been implicated in a scandal related to the procurement of vital medicines (Асан, A. 2022).

As noted in a public finance review by the World Bank (2023: 20), the use of quasi-fiscal activities (off-budget spending) has substantially increased when comparing the period 2011-2015 and 2016-2021, from 1.13% of GDP on average in the former, to 3.65% of GDP in the latter. The World Bank acknowledged some improvements in budget transparency but underscores the necessity of incorporating quasi-fiscal activities6da17acd672c into the fiscal framework (Assaniyaz 2023; World Bank 2023).

The Anti-Corruption Agency (2022: 10) points out that the mechanisms for allocating other forms of government support, such as grants, loans and subsidies, result in their inefficient use due to the issuing bodies not specifying final indicators of success for the use of such funds. The latest PEFA (2018) assessment on Kazakhstan also emphasised the need for better clarity on the links between policy instruments and objectives, with a more comprehensive explanation of performance targets. This can lead to excessive discretion in the distribution of these funds and thus create opportunities for unscrupulous officials to divert resources towards politically connected businesses.

Kazakhstan’s Anti-Corruption Agency (2022: 20) also stresses that the current system of state audit bodies and financial control needs optimisation to eliminate duplication of functions and improve their independence. Along these lines, the World Bank (2023: 142) stresses that, throughout the budget cycle, legislative scrutiny and oversight are present, yet audit institutions exhibit limited independence. Public audit is performed as both internal and external audits (GRECO 2022b). Internal audits for all public bodies receiving budget funds are conducted by the internal audit committee of the Ministry of Finance (GRECO 2022b). Until 2022, the committee of accounts performed external audits, overseeing the execution of the state budget (GRECO 2022b: 55)

Although the committee of accounts nominally provided independent oversight, it was assessed as lacking independence (World Bank 2021). In 2022, it was committee of accounts was reformed into the supreme audit chamber (Official Information Source of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan) with a widened mandate to audit the quasi-public sector and regional budgets in addition to the national budget (Gov.Kz no date). In 2022, it audited nine national projects implementing 8.1 trillion tenge (US$21 billion in budget funds) and found that seven had poor efficiency.

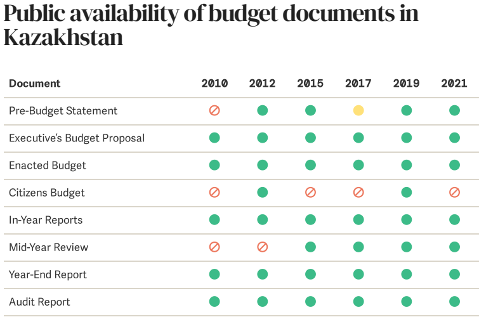

Finally, although improvements have been made regarding open data by making budget documentation and information available online, important issues remain. Namely, there is little evidence that increased transparency has contributed to higher citizen engagement in the PFM cycle (World Bank 2023). While the draft and approved budget are made available to the public, parliament receives more detailed information, including estimations and calculations, and can request further information (World Bank 2023: 144).

Figure 2

Source: Open Budget Survey 2021

Institutional and procedural gaps in public procurement

Despite government reforms in the public procurement process in Kazakhstan, corruption and inefficient spending persist (Brown and Tarnay 2023). Recent research indicates that public officials and suppliers are complicit in corrupt practices, and some interventions, such as monitoring and control, have failed to tackle the corruption problem (Khamitov et al. 2022).

In 2020, public procurement in Kazakhstan accounted for 7% of the country’s GDP and 35% of government spending, and it is estimated that every fifth corruption offence is committed in this area (Anti-Corruption Agency 2022: 11; IMF 2022: 35). Several structural and historical factors contribute to corruption risks in the area of public procurement, including the fragmentation of the legislative framework, a lack of a single and unified implementation approach, and a consistent development strategy, often leading to artificially inflated purchase prices (Anti-Corruption Agency 2022: 11). The procurement system in Kazakhstan is decentralised, with different government agencies and state-owned enterprises managing specific procurement projects (International Trade Administration 2022; OECD 2019). While the Ministry of Finance deals with developing procurement policies, the Committee for Public Procurement is tasked with enforcing the laws and regulations pertaining to public procurement (International Trade Administration 2022).

The authorities have recently made efforts to improve transparency and fairness in the bidding and winner selection process, by preparing a new public procurement law, developing fiscal risk assessments covering public-private partnerships, and setting up a new web-based platform for public procurement to encourage an open and transparent bidding process (IMF 2022: 35).

A draft of a new public procurement law introduces several provisions aimed at improving transparency and reducing corruption.922934d886dc These measures include allowing greater access to public tenders, promoting broader use of online procurement, and focusing on quality of goods and services over price (IMF 2022: 36).

The adoption of the e-procurement system provides an opportunity for civil society to monitor the public procurement process and more easily identify corruption risks (Brown and Tarnay 2023; see also OECD 2019). A monitoring coalition of 15 civil society organisations in Kazakhstan relies on this platform to promote transparency, fair competition and efficient spending. They have contributed to detecting corruption offences and campaigning for the introduction of changes to procurement laws and practices (Brown and Tarnay 2023).

Since 2021, one monitoring organisation, Adildik Joly, has identified high-risk procurements worth US$42 million and detected cases of corruption leading to fines totalling US$511,ooo (Brown and Tarnay 2023). One study focusing on 2020 found that only 1% of public procurement procedures had adequate technical specifications, and single-sourced procurements were the most common across government for acquiring goods, services and works in Kazakhstan (Aitenova et al. n.d.). The IMF (2022: 36) likewise found that while there have been improvements in the transparency of public procurement processes; single bidder contracts and direct negotiations still constituted around half of all contracts.

Another study identified several factors limiting transparency in public procurement in Kazakhstan, including inconsistencies between the data reported by the Ministry of Finance and that shown on the procurement website, as well as difficulties for foreign bidders to access government procurement opportunities, resulting in limited competitiveness (Dairabayeva et al. 2021). However, companies based in member states of the Eurasian Economic Union can bid for state procurement tenders in Kazakhstan (EUAU 2023).

A persistent challenge is that the e-procurement system does not encompass quasi-government entities and sovereign wealth funds, as they fall outside the purview of the public procurement law (Brown and Tarnay 2023). This omission opens space for corruption, for example, in the forms of embezzlement of funds and conflicts of interest in procurement procedures (Brown and Tarnay 2023). Given that two-thirds of public spending is done through an opaque quasi-governmental sector, bringing these types of spending under a single platform would arguably improve competition and reduce corruption risks (IMF 2022; Brown and Tarnay 2023).

Main sectors and areas affected by corruption

According to human rights NGOs, corruption in Kazakhstan is widespread, particularly within the executive branch, law enforcement, local government administration, the education system and the judiciary (US Department of State 2022).

Based on convictions data from 2021, the highest number of civil servants convicted for corruption came from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, local executive authorities, Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Defence (Mitskaya 2023: 3).

This section focuses on three areas particularly prone to corruption: the police and military, the justice sector and lower-level government administration.

Police and military

According to survey evidence, official statistics and observational data, various forms of corruption are widespread in the police and military, including bribery and corruption in procurement processes.

The GCB (2016) survey then suggested that the police have the highest bribery rate in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Specifically, 47% of responding households reported having paid a bribe to the road police in Kazakhstan (Pring 2016: 19).

Statistics for convictions in 2021 show that the Ministry of Internal Affairs topped the list with 159 convictions, while the Ministry of Defence ranked fourth with 28 convictions (Mitskaya 2023).

In 2023, the former chief of Kazakhstan’s Border Guard Service, Darkhan Dilmanov, was detained along with several of his subordinates on corruption charges (RFE/RL 2022). In a statement, the KNB mentioned an investigation into possible abuse of office while supervising the flow of goods along the Kazakhstan-China border (RFE/RL 2022).

Corruption risks are also evident in public procurement contracts involving both sectors. For instance, following an investigation of the procurement monitor Zertteu, an Almaty police chief was forced to terminate a contract for protective equipment, as it was revealed that it was planned to be awarded at inflated prices (Hrytsenko 2021).

The unrest in January 2022, as well as the Russian war in Ukraine, led to an increase in defence spending in Kazakhstan, putting corruption vulnerabilities in this sector under the spotlight (Kumenov 2022b). In February 2022, a military commission met to discuss ways of rooting out efficiency-reducing corruption from the armed forces and committed to increase openness and transparency while reducing bureaucracy (Kumenov 2022b). There have been many corruption scandals over the years, particularly involving procurement of overpriced and low-quality weaponry, leading the Ministry of Defence to pay special attention to this issue. For example, they announced that military personnel involved in procurement processes will have to undergo lie detector tests (Kumenov 2022b).

Justice sector

The constitution of Kazakhstan guarantees the independence of judges in the administration of justice, while the Law on Judiciary lays out three different instances of the court system: district courts, regional courts and the supreme court (GRECO 2022: 15).

In practice, however, corruption poses a serious challenge for the justice system as judges are subject to political influence, among other vulnerabilities (Freedom House 2023). Namely, judiciary is effectively subservient to the executive branch, considering that the president nominates or directly appoints judges following the recommendation of the Supreme Judicial Council, which is itself appointed by the president (GRECO 2022: 16; Freedom House 2023).

Over the last three years, 30 judges have been prosecuted, while 15 received prison sentences, which is more than in the previous eight years combined (Mitskaya 2023: 4). For example, in December 2023, the former chairman of the administrative board of the Kostanay regional court, Aksar Darbaev, was sentenced to nine years in prison for receiving a bribe amounting to 19 million tenge (app. US$40,000) (Suspectors 2023). He was detained by officers of the national security committee (KNB) in 2022 while receiving the bribe (ACCA 2022).

According to Freedom House (2023), long pre-trial detentions and arbitrary arrests occur in Kazakhstan, and politically motivated prosecutions and prison sentences are common against activists, journalists and the opposition.

The Anti-Corruption Agency (2022: 5) notes some recent improvements by, for example, establishing electronic systems for pre-trial investigations and administrative proceedings.

A 2020 survey by SANGE Research Center (n.d.) indicated low levels of public trust in the judiciary; 41.2% of respondents agreed with the statement that that judges are appointed to their positions with connections or for money, 26% disagreed and 32.8% could not answer.

Local government administration

Local government in Kazakhstan operates in oblasts, regions, cities, municipal and rural districts, as well as villages and communities that are not part of rural districts. Concerning the number of crimes committed by civil servants and executives, the Ministry of Interior tops the list in all years (2008-2017), followed by akimats (mayoral offices),65d1fc7d8772 penitentiary service employees and military personnel (Shibutov et al. 2018). The general prosecutor’s office (QamQor n.d.) reported that 15 akims (mayors) and 144 employees of akimats were implicated in corruption crimes in 2022.

An example from 2018 is that of the former Almaty Akim, Viktor Khrapunov, was convicted along with his wife in absentia, for misappropriation and embezzlement of entrusted property, fraud, money-laundering and abuse of office, bribe taking and creating and leading a criminal group, causing the damage to the state amounting to US$250 million (Astana Times 2018). He was sentenced to 17 years in prison, while his wife received a 14-year sentence (Astana Times 2018).

Legal and institutional anti-corruption framework

International conventions and initiatives

Kazakhstan has ratified a number of conventions and treaties and joined several initiatives:

- It has been a member of the OSCE since 1992.

- It has been a participant of the Istanbul Anti-Corruption Action Plan (a sub-regional peer review programme within the framework of the OECD Anti-Corruption Network for Eastern Europe and Central Asia) since 2004.

- It ratified the UN Convention Against Corruption in 2008.

- In 202o, the UNDP and Kazakhstan’s Anti-Corruption Agency were undertaking joint initiatives on anti-corruption monitoring, developing a methodology for external corruption risk assessment, promoting integrity principles and engaging civil society to implement an anti-corruption strategy (UNDP 2020; Cornell et al. 2021).

In terms of the Council of Europe (CoE), Kazakhstan joined Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) in January 2020. GRECO published its joint first and second round evaluation report of Kazakhstan in June 2022.

It found that corruption presents a serious concern rooted in various sectors and institutions in Kazakhstan, but that the lack of reliable information obscures the real extent of this problem. Nevertheless, based on available evidence, GRECO (2022a) highlighted gaps in the anti-corruption framework, a lack of responsiveness in policymaking and state control of the media, among other identified challenges, and listed 27 recommendations for the state to address. These recommendations cover many of the key corruption vulnerabilities in Kazakhstan such as conflicts of interest in public procurement and public investment procedures.

According to a report from the Anti-Corruption Agency on the implementation of 2022-2026 strategy, Kazakhstan was to report to GRECO on the implementation of the recommendations in September 2023 (Anti-Corruption Agency 2023b), following which GRECO will assess the implementation in line with a specific compliance procedure (GRECO 2022b). As of the time of writing, it is unclear when this assessment will be finalised. Nevertheless, there is evidence to suggest that the state has taken measures to implement many of the recommendations, including:

- In response to recommendation 3, the government of Kazakhstan supported a set of legislative amendments on judicial reforms. These amendments, among other goals, aim to improve the work of the judicial jury and the commission on the quality of justice, strengthening the independence of judges (Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2023b).

- In response to recommendation 6, the action on “promoting transparency and action against economic crime” in Central Asia supported Kazakhstan authorities with enhancing inter-institutional cooperation while conducting financial investigations related to corruption and money-laundering (Council of Europe 2023). In February 2023, Council of Europe organised training, gathering 35 investigators and prosecutors from the Anti-Corruption Agency, general prosecutor’s office, academy of law enforcement agencies, financial monitoring agency and national security committee (Council of Europe 2023).

- In response to recommendation 11 to strengthen the systems and controls for tracing criminal proceeds and identifying ultimate beneficial owners, the government introduced a new legislative act to counter the legalisation (laundering) of proceeds from crime and the financing of terrorism (Anti-Corruption Agency 2023c).

- In response to recommendation 15, the government committing to introducing a register of corrupt officials in 2023 to enable employers to assess a potential candidate for integrity and to strengthen the liability of legal entities for committing corruption offences (Kazinform 2023b; Ишекенова 2023). As of January 2024, the register was under consideration by Parliament (Zakon.kz, 2024).

- In response to recommendation 20, anti-corruption legislation was amended in early 2023 to strengthen the protection of whistleblowers (Anti-Corruption Portal 2023).

- In response to recommendation 21, the government made efforts to improve transparency and fairness in bidding in public procurement, by preparing a new draft law on public procurement, that introduces provisions to allow greater access to public tenders, promote the use of an online platform, focus on the quality of goods and services over price, among other improvements (IMF 2022).

- In response to recommendation 22, the government introduced a beneficial ownership register and empowered the financial monitoring agency to maintain it (KPMG 2023).

Furthermore, in 2022, Kazakhstan began the process to accede to the CoE Criminal Law Convention on Corruption which enhances international cooperation on corruption investigations (Astana Times 2022).

Domestic legal framework and initiatives

In 2015, Kazakhstan adopted the Anti-Corruption Law, outlining anti-corruption measures, defining bodies responsible for countering corruption, as well as their authorities, and considering measures for recovery of illegally obtained property and other benefits obtained through corruption (GRECO 2022b).

In the same year, Kazakhstan adopted a new anti-corruption strategy for 2015-2025, with goals of reducing corruption in the civil service, quasi-state and private sectors, judiciary and law enforcement bodies (OECD 2017; Shibutov et al. 2018). This strategy focused on measures for preventing conditions that are favourable to corruption, rather than countering the consequences of corruption (Bakhyt 2015).

Several other laws and by-laws that included anti-corruption provisions were adopted, including the Law on Civil Service, anti-corruption monitoring guidelines, the 2016 standard guidelines for the internal analysis of corruption risks and the 2017 guidelines for performing an external analysis of corruption risks (GRECO 2022b: 5; Shibutov et al. 2018). The 2016 standard guidelines for the internal analysis of corruption risks set out the procedure for conducting corruption risk analysis by state bodies, organisations and the quasi-public sector (Ministry of Justice 2015). The guidelines state that internal analysis is to be used to develop measures to eliminate the causes and conditions that are conducive to corruption (Ministry of Justice 2015). Internal analysis, according to these guidelines, is conducted based on the decision of the head of the respective body (Ministry of Justice 2015).

Other domestic legislations that include corruption provisions are the criminal code, the code on administrative violations, the Law on the Procedure for Interacting with Individuals and Legal Entities, the Law on State Services, the Law on Administrative Procedures and the Law on Permits and Notifications (Shibutov et al. 2018: 18).

The law on access to information was passed in 2015, and it establishes the right to request and receive information from state bodies, institutions and businesses, among public organisations (Cornell et al. 2021).

In December 2017, the government adopted the programme Digital Kazakhstan, aimed at applying information technology to transform the way that citizens engage with the government and with each other in the private sector (Cornell et al. 2021; E government n.d.). Kazakhstan underwent comprehensive digitalisation programmes in recent years, resulting in the majority of public services being available online, and open data available for budget and public procurement. These initiatives increased the transparency of how public funds are spent and contributed to easier corruption risk detection (GRECO 2022b: 5). One example is an interactive map of open budgets for schools, kindergartens, health institutions and road construction (GRECO 2022b: 5).

In 2019, President Tokayev developed a concept of the “hearing state”, aimed at enabling efficient interaction between citizens and state institutions, and prompt responses to citizens’ concerns through e-government platforms (Long 2020). Following Tokayev’s announcement, the Anti-Corruption Agency set up a hotline, and established service centres in all regional centres in Kazakhstan (GRECO 2022b: 5).

In 2020, Tokayev signed a law amending the work of civil servants, introducing a complete ban on gifts, material rewards and services of any value applying to civil servants and their families (Yergaliyeva 2020). In addition, the law also prohibits civil servants from hiring relatives, and candidates for public office must inform the administration about any relative who works for a government organisation (Yergaliyeva 2020). As reported by the Anti-Corruption Agency, following these amendments, 15 politicians and 39 civil service managers and 5 managers of state-owned firms were arrested (Cornell et al. 2021: 91-92).

In 2020, the Anti-Corruption Agency initiated anti-corruption awareness raising projects, resulting in 18,000 online events with a coverage of 9.7 million people (GRECO 2022).

Since January 2021, Kazakh officials and their spouses are required to submit their income and property declarations, as part of the phased introduction of universal income and property declarations by 2025 (US Department of State 2023; E government 2023). In the second phase, that started in January 2023, this requirement expanded to employees of government bodies and employees of the quasi-public sector and their spouses (E government 2023). Nevertheless, there is currently no mechanism in place to enable the public’s access to this information.

Latest legislative changes and initiatives

An anti-corruption policy concept for 2022-2026 was adopted by presidential decree no. 802 on 2 February 2022 (Anti-Corruption Agency 2022). This document maps out the current anti-corruption landscape in Kazakhstan, and discusses key issues that need to be addressed in the medium term, including:

- petty corruption

- corruption risks in the public and private sectors

- corruption vulnerability of the budget allocation process

- lack of transparency in procurement

- high level of state participation in the economy

- inadequate mechanisms of interaction between civil society and state

- imperfect monitoring system of effectiveness of anti-corruption measures

A revised version of the strategic plan for the development of Kazakhstan until 2025 was approved in 2022 under the name National Plan for Development of Kazakhstan until 2025.

In 2022, President Tokayev suggested that money seized from corrupt officials be used to fund school construction (Kazinform 2022). In 2023, the first school was constructed using funds seized from corrupt officials in the Aktobe region (Kazinform 2023a).

On 3 January 2023, President Tokayev signed the law on combating corruption, which introduces penalties against officials for discrepancies between their expenses and incomes, set to enter into effect in 2027 (US Department of State 2023).

In July 2023, Tokayev signed a law on the return of illegally acquired assets. The mechanism for this applies to persons holding positions of public responsibility, positions in state legal entities, quasi-public sector and those affiliated with them. For the law to apply, a person or an entity must have assets of over US$100 million (Tastanova 2023).

In October 2023, the Kazakh prosecutor general’s office set up the committee for asset recovery (Sakenova 2023). The committee was previously established by the president’s decree and is responsible for asset recovery. As such, its core responsibilities are searching and recovering illegally obtained assets, but it also has investigative powers (Sakenova 2023).

Starting from January 2024, the obligation to submit income and property declarations will expand to heads, founders of legal entities and their spouses, and individual entrepreneurs and their spouses (E government 2023).

Institutional framework

Anti-Corruption Agency of the Republic of Kazakhstan

In 2014, the Agency for Civil Service Affairs and Anti-Corruption was established, and it was transformed into the current Anti-Corruption Agency in 2019 (GRECO 2022b). These reforms provided more autonomy to the agency as it is now a standalone entity (Toqmadi 2020).

The agency is directly subordinated to the president of Kazakhstan and is tasked with the development and implementation of the anti-corruption policy, coordination in countering corruption, and identification, suppression, disclosure and investigation of corruption offences (GRECO 2022b: 4; Anti-Corruption Agency 2023).

GRECO (2022b) recommended that anti-corruption efforts need to translate into more impact driven results with regards to the Anti-Corruption Agency as well. Specifically, they suggest better and more structured prioritisation of the roles of this body, considering the wide authorities that it has (GRECO 2022b).

In a 2023 survey from the statistics bureau, 43% of respondents said they trusted the agency , an increase from 30% in 2022.

Commission on anti-corruption issues

This advisory and consultative body on anti-corruption issues operates under the president of Kazakhstan and was established in 2002 (Ministry of Justice 2002).

Its primary objective is development and adoption of coordinated measures to counter corruption. This includes submitting proposals to the president for improving anti-corruption legislation as well as monitoring and analysing the state of anti-corruption efforts, among other responsibilities (Ministry of Justice 2002).

Commission on the return of illegally acquired assets

In June 2023, President Tokayev set up the commission on counteracting the illegal concentration of economic resources with the key goals of recovering money laundered abroad and exposing monopoly concentrations of economic resources achieved using illegal means (Lillis 2022b). The commission will develop a strategy for ensuring the return of illegally acquired assets from abroad to Kazakhstan (Kazinform 2023c). In 2023, prosecutors announced that they had recovered US$1.7 billion of illegally acquired assets (Kumenov 2023).

Specialised anti-corruption bodies

Each law enforcement body has its own internal security units, whose task is to prevent and counter corruption within these bodies (GRECO 2022b: 20). When it comes to other state bodies, this role is mostly placed with the heads of human resources and internal audit units (GRECO 2022b: 20).

Ethics commissioners

Established in 2015 by presidential decree, they are tasked with advising civil servants on compliance with legal requirements in the areas of civil service, countering corruption, and the code of ethics, among other roles (GRECO 2022: 45). GRECO (2022) suggested that ethics commissioners could play a greater role in curbing corruption if certain obstacles were to be removed. Specifically, during their visit, GRECO (2022: 58) did not receive sufficient information about whether ethics commissioners had sufficient support staff.

Other key institutions with anti-corruption roles include:

- Ministry of the Interior

- national security committee

- prosecution bodies

- financial monitoring agency

Other stakeholders

Civil society

In general, civil society in Kazakhstan is weak and confined to the margins where it is less likely to interfere with the design and implementation of state policies (BTI 2022). Civil society organisations also face structural challenges, such as low access to stable funding, a lack of technical skills and human resources (BTI 2022). In 2019, a national council of public trust was formed with the official aim of involving civil society more closely in policymaking (BTI 2022). Despite government claims that civil society has been able to contribute to several draft laws, there is still a very limited degree of its involvement in decision-making (BTI 2022).

Nevertheless, over the last several years, coalitions of civil society organisations have emerged to engage in monitoring how public money is being spent, particularly in the area of public procurement, following the government’s promotion of public participation in procurement monitoring. These include:

- A formal coalition of 15 civil society organisations; Kun Jarygy has been formed to engage in monitoring of public procurement and created the website www.prozakup.kz (Brown and Tarnay 2023)

- Zertteu Research Institute, that engages in research that promotes dialogue on the budget process, based on the principles of transparency, accountability and public participation

- Integrity Astana engages in research on budget transparency and public procurement, among other priorities

- Adildik Joly, created by anti-corruption activists, promotes integrity and curbs corruption; this NGO has 17 branches in all regions in Kazakhstan (Red Flags n.d.).

- Transparency International Kazakhstan, an accredited national branch of Transparency International is active in conducting anti-corruption research and advocacy

Media

According to the Freedom House (2023), media independence is very limited in Kazakhstan, as most of the media sector is under the control of government-friendly owners. Harassment and the shutdown of independent outlets and journalists are common, and authorities resort to internet blackouts to limit access to media outlets (Freedom House 2023). In addition, arrests and assaults are also used to prevent coverage of major events (RSF 2023). This was particularly evident following the unrest in January 2022, when the government shut down access to internet in the country for five days (Freedom House 2023).

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF 2023) despite the improvement in the quality of online news, Kazakhstan is experiencing growing control of the internet. There are only a handful of independent media outlets, with others being regime propaganda outlets (RSF 2023). Independent media outlets include:

- vlast.kz

- Uralskaya Nedelya

- KazTAG press agency (RSF 2023)

- Scores range from -2.5 to 2.5 (higher scores correspond to a better governance) (World Bank 2023).

- UWOs were introduced in the UK in 2017 to tackle organised crime and grand corruption emanating from kleptocrats (University of Exeter 2022).

- Services in the survey included the road police, public agencies issuing official documents, the civil courts, public education (primary or secondary), public education (vocation), public medical care, public agencies in charge of unemployment benefits or any other public agencies in charge of other social security benefits (Pring 2016: 18).

- These include, for example, payments for social services, public infrastructure and fuel subsidies, which are not recorded as part of the national budget (see EITI 2020; World Bank 2023: 20).

- In Tokayev’s 2023 State of the Nation Address he states that he instructed the government to draft the new public procurement legislation that would address the shortcomings of the current framework, such as frequent appeals and a lack of transparency (Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2023a).

- Local government in Kazakhstan serves to resolve local-level issues through local government institutions, including Maslikhats (the main local representative body) and akims (heads of local government) (Shibutov et al. 2018).