Query

Our institution is looking for guidance to: 1) incorporate gender considerations and; 2) incorporate human rights into anti-corruption programming and would like to know if there are successful practices gained from other partners to do this.

Caveat

The literature on mainstreaming human rights in anti-corruption is scarce. This answer draws on reports and guidelines of mainstreaming human rights into the broader development agenda.

Summary

There is a broad consensus that the anti‑corruption and human rights agenda can mutually benefit from each other, but research is more advanced on how to mainstream gender in anti-corruption interventions and to ensure that men and women are equally benefitting from anti-corruption programmes and that programmes have no (unintended) consequences that disproportionally affect men or women.

Mainstreaming gender and human rights into anti-corruption interventions requires taking into account gender and human rights considerations throughout four steps of the programme cycle, from the very early stage of strategy setting and conception of programme activities to programme design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

Why mainstream gender and human rights into anti-corruption programming?

The fact that corruption affects different populations differently and can be an infringement on enjoyment of human rights has received increasing attention over the last years. While more research has been conducted on the question of how men and women are differently affected by corruption, the literature on the link between corruption and human rights is still scarce. There is a consensus on the need to mainstream gender in anti-corruption interventions to ensure that men and women are equally benefitting from anti-corruption programmes and that programmes have no (unintended) consequences that disproportionally affect men or women.

The understanding of the linkages between human rights and corruption and the need to integrate human rights concerns into anti-corruption programming has gained less attention in the literature. The linkages between human rights and corruption are explored from three different perspectives, mostly investigating: i) whether corruption can be characterised as a violation of human rights; ii) the effects of corruption on the enjoyment of human rights and; iii) whether and how the human rights and the corruption agendas can be integrated (Chêne 2016).

Gender and anti-corruption programming

The rationale for mainstreaming gender in anti-corruption programmes

The importance of including a gender angle in the discussion of corruption has been widely discussed since 2001. There is evidence that understanding gender power relations and inequalities can improve the design of governance and anti-corruption interventions (UNODC 2013). Research shows that there are differences in how men and women perceive, experience and tolerate corruption and that women are less likely to pay bribes. In addition, while the underlying causal mechanisms are still debated, the participation of women in public life has also been linked to lower levels of corruption in many countries of the world. At the same time, corruption has also been shown to hinder the active participation of women in high level positions in politics and business (Sim et al. 2017).

The research has also shown that the impact of corruption is highly gendered. Due to power imbalances and different gender roles in society, women are often proportionally more vulnerable to corruption and face higher corruption risks in certain sectors, e.g. service delivery (Boehm and Sierra 2015). Recent research also shows the importance of understanding gender specific forms of corruption such as sextortion: the abuse of power to obtain sexual benefits or advantage (IAWJ 2012). To address the gendered experiences, forms and effects of corruption and to assure that all anti-corruption measures benefit men and women equally, it is paramount to mainstream gender into anti-corruption efforts.

Defining gender mainstreaming

The process to include gender in all aspects of programme development and implementation has been coined gender mainstreaming. Gender mainstreaming is an essential tool for achieving gender equality and has been defined by the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (1997) as “the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres”. The ultimate goal is to promote and achieve gender equality.

Therefore, in the context of anti-corruption programming, the key question for gender mainstreaming is to assess whether the planned anti-corruption intervention is likely to promote gender equality or not (AFDB 2009). Socially constructed roles, activities, attributes and behaviours, personality traits, relationships, power and influence that a society conceptually attributes to men and women need to be considered at all stages of the anti-corruption programme cycle.

It is important to note that gender mainstreaming does not only refer to women but focuses on the group that has been discriminated against, which can also include men when their perceived gender roles lead to discrimination. It requires including a thorough understanding of gender norms, roles and “the inclusion of perceptions, experiences, knowledge and interests of women as well as men, within policymaking, planning and decision-making” (UNODC 2013 p.7).

Gender mainstreaming should not be seen as an isolated or separate exercise but an integral part of all the organisation’s operations, from developing the strategic framework of interventions, to designing, implementing or evaluating country or regional programmes and projects, conducting research and developing tools, etc. Gender considerations should be integrated from the conception of programme activities, whether at the national, regional or global levels (UNODC 2013).

Human rights and anti-corruption programming

The links between corruption and human rights

While the relationship between human rights and corruption has gained less attention, the literature discusses three it main questions.

Firstly, some argue that corruption should be considered a violation of human rights as it undermines the rule of law, which is a necessary condition for the respect of human rights, negating the very concept of human rights. Some have even discussed that certain cases of corruption should be looked at as a crime against humanity which would allow for universal jurisdiction and access to the International Criminal Court (Banquetas 2006). Yet, this approach is still being debated as manyit is unrealistic and only covers very specific corruption instances. There are also instances where corruption directly violates human rights, e.g. when fair and transparent elections are undermined, access to a fair trial is denied or judicial decisions are bought. (Chêne 2016). The principle of non-discrimination canalso be affected when a person has to pay a bribe to get a favourable treatment or access to public services.

Secondly, corruption has been shown to have a negative effect on the enjoyment of human rights. Where corruption is pervasive, it is practically impossible to protect, respect and fulfil human rights. Corruption weakens the ability of states to adequately respect and protect the enjoyment of human rights, it compromises the ability of security institutions to provide for security for the population and undermines citizen’s access to justice and political representation (Chêne 2016; Human Rights Council 2015). Public resources that are needed to ensure human rights are diverted, and development outcomes are undermined through corruption. In this manner, corruption undermines the ability of the state to sufficiently provide for human rights. As the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) states, corruption “can have devastating impacts on the availability, quality and accessibility – on the basis of equality – of human rights-related goods and services” (OHCHR Website). In addition, systemic corruption exacerbates inequalities and constitutes an obstacle for the right of all people to “pursue their economic, social and cultural development”.

Thirdly, there is a growing consensus in the literature that the fight against corruption and the protection of human rights can mutually benefit from each other and should be integrated to some extent. Some existing international human rights mechanisms may be useful in the fight against corruption, and vice versa. For example, the respect of freedom of association, access to information and freedom of the press is indispensable for countering corruption. Some authors go as far as arguing that, where rights are guaranteed and implemented, corruption is expected to drastically reduce. Similarly, it can be expected that reducing corruption may have a positive impact on human rights protection.

Therefore, many authors argue for integrating the anti-corruption and human right agendas. Hemsley (2015) even goes as far as arguing that, since corruption directly and indirectly violates human rights, states are required to fight corruption as part of the duties enshrined under the core human rights treaties. Multiple Human Rights Council resolutions (the latest in July 2017A/HRC/RES/35/25) explicitly call for the “cooperation and coordination among stakeholders and national, regional and international levels to fight corruption in all its forms as a means of contributing positively to the promotion and protection of human rights”. Peters (2015 p.27) identifies several points that would have to be taken into consideration for human rights treaty bodies to mainstream anti-corruption into their work.

- Corruption needs to be included as a point to be addressed in all guidelines, concluding observations of the committees as well as the mandates of the human rights special rapporteurs.

- Anti-corruption NGOs should participate in the Universal Periodic Review and treaty monitoring.

- A “general comment on corruption and human rights” applicable to all treaties should be considered.

- National human rights institutions should include anti-corruption mandates.

However, this measure has caveats. There are a limited number of international enforcement mechanisms and, at the national level, corruption in the judiciary might prevent courts from condemning states for human rights violations.

Importantly, anti-corruption initiatives need to consider that they can potentially be in violation of human rights (Human Rights Council. 2015). In countries where human right violations are widespread, anti-corruption prosecutions can conflict with fundamental rights of privacy, due process and fair trial if conducted without respecting human rights standards. In such contexts, mainstreaming human rights in anti-corruption interventions can be useful to try to minimise the risk as it requires integrating human rights considerations from the beginning of the project cycle, and programmes can be designed accordingly.

Promoting a human rights based approach to anti-corruption

In 2004, the United Nations agreed that human rights must be mainstreamed into all its programmes and defined the three main aspects of a human rights based approach (HRBA) (UNDP 2004):

- All programmes of development cooperation, policies and technical assistance should further the realisation of human rights as laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and other international human rights instruments.

- Human rights standards contained in, and principles derived from, the UDHR and other human rights instruments guide all development cooperation and programming in all sectors and in all phases of the programming process.

- Development cooperation contributes to the development of the capacities of duty-bearers to meet their obligations and/or of rights-holders to claim their rights (UNDP 2004).

Such a human rights based approach to anti-corruption can add value to countering corruption by giving the anti-corruption agenda more weight in political and moral terms. This would mean “putting the international human rights entitlements and claims of the people (the ‘right-holders’) and the corresponding obligations of the State (the ‘duty-bearer’) in the centre of the ant-corruption debate and efforts at all levels, and integrating international human rights principles including non-discrimination and equality, participation and inclusion, accountability, transparency, and the rule of law” (OHCHR. 2013. p. 5).

One main argument for using a human rights based approach in anti-corruption is that of empowerment. “The human rights approach can elucidate the rights of persons affected by corruption, such as the rights to safe drinking water and free primary education, and show them how, for instance, the misappropriation of public funds in those areas interferes with their enjoyment of the goods to which they are entitled” (Peters 2015 p.26). Furthermore, when individuals are empowered to know their rights they also are able to hold governments accountable and demand more transparency.

Similarly, the Human Rights Council (2015) agreed that shifting the focus in anti-corruption away from the individual perpetrators that criminal law focuses on will lead to an acknowledgement of the responsibility of the state and a better status of victims. Lastly, as Peters (2015) discusses, moving away from a solely criminal law approach to anti-corruption will “shift the focus away from repression toward prevention” and can change the burden of proof to the state (p. 26). ICHRP (2010 p.8) identifies additional benefits of integrating human rights principles within anti-corruption. This would help anti-corruption initiatives to:

- address social, political and economic factors that enable corruption;

- identify the claims of marginalised groups against the state;

- oppose abuse of power, violence, discrimination and impunity;

- address the rights of groups who suffer discrimination;

- empower victims of corruption; and

- use the accountability mechanisms of the human rights system.

This line of argument can lead to a clear recommendation for mainstreaming human rights into anti-corruption, which then would make the realisation of human rights a direct goal of anti-corruption programmes, and vice versa.

While the literature on mainstreaming human rights into anti-corruption is scarce, the UN has, since 2009, institutionalised the mainstreaming of human rights into development work, which can also be seen as a guide for anti-corruption programmes. The UN Practitioners’ Portal on Human Rights Based Approaches to Programming gives information on mainstreaming human rights standards and principles into the development work.

Overall it is important that mainstreaming gender and human rights is not a goal in itself but rather a process to reach gender equality and justice. The human rights based approach and gender mainstreaming should also be considered mutually reinforcing and complementary and can therefore be undertaken simultaneously (OHCR 2006).

The process of mainstreaming gender and human rights in anti-corruption programming: an overview

Mainstreaming: the process

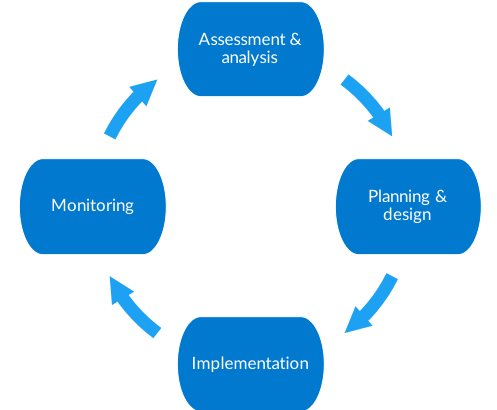

Mainstreaming either gender or human rights into anti-corruption programmes and policies require agencies to look at the human implications of any activity, acknowledge the differences between women and men and different groups, and address the potential differential impacts of the intervention on men and women and on human rights. Activities then need to be designed in a way that safeguards human rights and ensures that both women and men will benefit equally from the intervention. Considerations about gender and human rights have to be taken into account throughout four steps of the programme cycle. The figure below presents the different stages of mainstreaming that are applicable both for gender and human rights mainstreaming.

Source: UNDP 2012 p. 5

The first step for any programme or project consists of assessing the current situation and identifying gender or human right issues that need to be addressed. Gender and human rights considerations should be considered from the very early stage of strategy setting and conception of programme activities. At this stage, an initial assessment of the gender and human rights contexts and challenges and the impact of the planned activities on women and men and the enjoyment of human rights needs to be conducted and integrated into the programme design process (UNODC 2013).

Once these issues have been identified, the complete programme/project documents based on the findings of the first assessment phase have to be completed. At this stage, the goals and objectives of the programme need to be examined and formulated in light of gender equality (UNODC 2013) and protection of human rights. This implies taking into consideration the potential implications of the programme on men and women and the enjoyment of human rights to develop gender-sensitive objectives, outcomes and outputs. More specifically, this means that: i) the gender constraints and issues to be addressed by the intervention need to be clearly articulated in the objectives of the programme or project; ii) the programme intervention areas should explicitly spell out the activities to address the gender issues that have been identified and; iii) realistic gender equality targets and indicators are developed (AFDB 2009). UNODC’s 2013 guidance note for mainstreaming gender in UNODC work provides guidance on key questions to consider at this stage of programme design when mainstreaming gender in the formulation of objectives, outcomes and outputs.

Continuous monitoring of the situation of gender and human rights should occur during programme implementation to ensure that all gender and human rights issues identified at the planning stage are effectively addressed in practice. This can involve conducting regular project reviews, collecting sex-disaggregated data, conducting training and capacity building, and raising awareness. Whenever challenges and gaps are identified at the implementation stage, they should be address and revised as soon as possible (UNODC 2013).

Lastly, the evaluation stage should identify strengths and weaknesses of the programme in terms of gender and human rights mainstreaming along with the impact of the intervention on men and women, analyse if gender and/or human rights have been built into every aspect of the programme cycle and recommend actions for the future (UNODC 2013).

Mainstreaming gender in anti-corruption

Mainstreaming gender into anti-corruption programmes is more common and therefore there is more information and experience on how to mainstream gender at each stage of the programming cycle.

Assessment and analysis

The gender perspective should not only be integrated at the programme or project level but also within the overall strategic framework (UNODC 2013). At the strategic and programmatic level, a comprehensive gender analysis needs to be conducted as part of the situation analysis to determine the viability of the governance intervention (AFDB 2009). Such analysis examines the differences between men and women, their respective characteristics, needs and priorities, the power dynamics shaping gender roles and the different impacts of the proposed policy or programme on men and women. This will help to design better formulated programmes that take into account the gendered impacts of the proposed policy or programme. (UNODC 2013)

Gender analysis typically has three main components: i) the collection of gender-sensitive data (sex-disaggregated data including statistics, interview results, etc); ii) the analysis of this data and; iii) a gender perspective analysing the causes and consequences of the gender differences based on established theories about gender relations. Tools for conducting such a gender analysis can include a desk study of legislation, key government documents and policies, broad consultations with gender experts, civil society representatives, women’s groups, interdivisional task teams, in-depth research projects or sociological surveys (UNODC 2013).

Five key questions need to be considered for gender mainstreaming in anti-corruption programmes (Sample 2018):

- Do women and men benefit equally from the project and how can we know that?

- Are women providing and accessing the information?

- Do women have a voice in decision making?

- Are there opportunities for engaging women’s organisations?

- Does the project present gender based risks?

- Does the project reach women across social, economic and ethnic/racial identities?

The analysis also needs to explicitly include questions of power dynamics which shape gender roles. UNODC (2013) identifies two areas that need special attention:

- The roles of men and women and their access to and control of resources, the different constraints they face and the opportunities available to both.

- The specific activities, conditions, concerns and needs of men and women and they role they (can) play in decision-making processes.

Planning and design

Based on this initial assessment phase, gender considerations need to be included into the planning of any anti-corruption programme, with gender objectives and targets clearly articulated in the programme documents. The UNODC guidelines also recommend ensuring that all templates, guidelines, tools and technical assistance materials have a gender perspective. Several issues should be taken into consideration when designing gender-sensitive policy objectives (UNODC 2013).

- Determine the gender dimensions of the goal that is supposed to be achieved.

- Does the objective make sure that both the concerns of men and women are adequately addressed, and does it bring improvements to both?

- How are the relations between men and women influenced by the objective?

- To what extent does the programme further gender equality overall, and does the objective include a commitment to change attitudes and institutions overall?

Gender considerations also need to be integrated into the resource mobilisation and budgeting process (planning, implementation, reporting and oversight) to make sure women’s concerns are properly reflected in the budget and that resource allocation equally benefits men and women. Earmarking funds and setting expenditure targets for gender equality programming is an important factor to ensure desired results. This can include allocating sufficient human resources to coordinate and oversee gender integration activities, allocating sufficient resources to hire gender experts or conduct gender activities, such as gender training for staff and project partners (UNODC 2013).

Gender-sensitive budgeting supports gender mainstreaming efforts by assessing the impact of government or organisation’s revenue and expenditure policies on women and men. This approach helps ensure that the necessary resources are allocated to achieve the goal of gender equality (UNODC 2013).

Budlender and Hewitt (2003) identify a five-step approach to engendering budgets:

- analysing the situation of women, men, girls and boys;

- assessing; the gender responsiveness of policies;

- assessing budget allocations;

- monitoring spending and service delivery;

- assessing outcomes.

Implementation

Gender considerations are equally important to take into account during the implementation phase. Throughout implementation, the project team must continuously raise awareness of how the anti-corruption interventions may affect men and women differently, and any policy should be designed with the goal of empowering women’s participation and building their capacity. The programme should also ensure that the institutional arrangements proposed are gender responsive and have sufficient capacity to implement the gender mainstreaming strategies and actions envisaged (AFDB 2009). Throughout the implementation, regular review meetings need to be held to evaluate the gender impact of the programme. Additionally, implementers should ensure that participation in the programmes is gender balanced and gender issues are included in monitoring and progress reports (UNODC 2013).

This also needs to take into consideration the importance of women’s empowerment to report corruption and demand accountability. Therefore, it is important to provide gender-sensitive reporting and complaints mechanisms that allow women and men to report incidence of corruption and demand accountability. This can include a wider range of considerations, for example, literacy rates of women are often still lower than those of men or they might have limited access to technologies, which should be taken into account when designing (online) reporting tools.

Monitoring and evaluation

This stage of the process focuses on tracking progress with regard to achieving the programme’s gender objectives and targets. It involves setting up a monitoring system that sets gender-sensitive project indicators and milestones, and ensures that all data collected throughout the project cycle is disaggregated by age, gender, ethnicity, etc (AFDB 2009). Gender-sensitive indicators and milestones aim to capture data that reflect the realities of men and women and how they have been affected respectively by the intervention (Ludec 2009).

Collecting sex-disaggregated gender-sensitive data also involves paying attention to how the data is collected and making sure it incorporates both women’s and men’s experiences when designing quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Gender-sensitive data collection methods typically involve a participatory assessment whereby male and female beneficiaries are consulted both separately and in mixed groups. The composition of the assessment teams also need to be gender balanced to ensure greater access to females (UNODC 2013). Furthermore, it is important to collect both quantitative and qualitative data and to ensure that the data collection tools used pick up gendered information (UNICEF 2012). Sufficient resources should also be allocated to ensure that gender-sensitive data can be collected (UNODC 2013).

This approach is made possible by making sure that the gender perspective is explicitly integrated into the evaluation’s terms of reference. The evaluators need to have expertise in gender; all relevant stakeholders need to be involved in the process, opinions of men and women need to be captured and evaluation questions prepared to specifically address gender (UNODC 2013).

For learning and future programmes, it is important to ensure that success and failures in achieving gender equality programme objectives are documented, including lessons learnt which can be taken into account and replicated in further anti-corruption interventions (AFBD 2009).

Practical guidance and lessons learnt

There is little publicly available documented practices of gender and human right mainstreaming from other partner agencies. Two gender mainstreaming programmes in anti-corruption work can be found at the UNODC and the Transparency Fund of the Inter-American Development Bank (formerly Anticorruption Activities Trust Fund).

The UNODC’s guide – on which this answer extensively draws – establishes how gender should be mainstreamed throughout the programme cycle, providing detailed practical guidance for each of the steps. Focusing both on the programme and strategic level, the guide gives information on the importance of identifying entry points for gender mainstreaming and identifying issues that need to be addressed. It recommends a number of key entry points for gender mainstreaming in its programme on countering corruption:

- enhancing national capacities to produce data and conduct statistical and analytical studies on corruption prevalence, patterns and typologies

- enhancing knowledge of challenges, policies and good practices with respect to the implementation of the UNCAC

- enhancing integrity, accountability, oversight and transparency of appropriate criminal justice institutions with a view to reducing vulnerabilities to corrupt practices

- enhancing capacity of national institutions to effectively raise awareness of corruption

- enhancing the role of civil society

Similarly, the Transparency Fund’s guide gives a step by step account on how the fund ensures that its projects are responsive to the needs of women and men. The guide includes a large set of question that organisations should ask themselves to ensure that gender is mainstreamed throughout the programme cycle. Most importantly, it provides a detailed list of suggested indicators and entry points for programming. The discussion is structured around the four transparency pillars: financial integrity, control systems, natural resource governance and open government. The guide and the list of indicators can be found here.

A SIDA brief on gender and corruption makes further practical recommendations on mainstreaming gender to counter corruption (SIDA 2015):

- Mainstreaming gender equality in anti-corruption interventions can be done through capacity development at different arenas: government, civil society and the media. Advocacy activities targeting policymakers can be conducted to raise awareness on the need to integrate the differential impact of corruption on men and women and design policies that address women and men’s specific concerns and experiences.

- Gender mainstreaming requires the systematic collection and analysis of gender disaggregated data.

- Anti-corruption interventions need to combine targeted anti-corruption policies with efforts to empower women in governance.

- It is also important to implement gender-responsive budgeting to ensure that budgets are more responsive to women’s needs.

- Anti-corruption programming can focus on increasing the number of women in government by promoting and supporting the political participation of women and their representation in the public sector in all stages of service delivery.

- Anti-corruption interventions should also improve access to information through promoting and advocating for an enforceable right to information for women and men.

Mainstreaming human rights in anti-corruption programmes

Little information is available on mainstreaming human rights into anti-corruption work, but much can be learnt from mainstreaming human rights into the development agenda. As already mentioned, within the UN agencies a human rights based approach (HRBA) is used as “a conceptual framework for the process of human development that is normatively based on international human rights standards and operationally directed to promoting and protecting human rights”.

The agencies agreed on the UN Common Understanding on a HRBA (UNCU) which is based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the nine core international human rights treaties. The key principles, which are also relevant for anti-corruption efforts are (UNDP 2012):

- All programmes, policies and technical assistance (including anti-corruption) should further the realisation of human rights as laid down in the UDHR.

- Human rights standards contained in, and principles derived from the UDHR and other human rights instruments, guide all development cooperation and programming in all sectors and in all phases of the programming process.

- Development cooperation contributes to the development of the capacities of duty-bearers to meet their obligations and/or rights-holders to claim their rights.

Under a human rights based approach, any anti-corruption efforts should contribute to not just fighting corruption but ensuring the realisation of human rights. This includes two perspectives. For one, it should lead to behaviour changes in the duty-bearer to respect, fulfil and protect rights, for the other it should entice the rights-holder to demand and exercise rights.

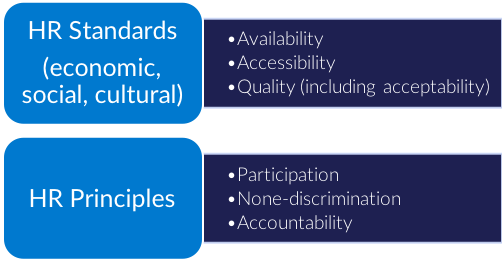

Mainstreaming human rights, according to the UNDP approach, is based on two major principles:

- The process of any anti-corruption policy or programme should be designed around the human rights principles of participation, non-discrimination and accountability

- The programme or policy outcomes have to adhere to the human rights standards of availability, accessibility and quality. These core principles and standards are shown in the figure below.

Source: UNDP 2012 p. 5

Human rights principles

Human rights principles should guide all phases of the programming/policy cycle, including assessment and analysis, planning and design (including setting of goals, objectives and strategies), implementation, and monitoring and evaluation (OHCHR 2006 p. 36). Not all of these will be relevant for anti-corruption programming, but this needs to be looked at in more detail.

Equality and non-discrimination

“All human beings are entitled to their human rights without discrimination of any kind on the grounds of race, colour, sex, ethnicity, age, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, disability, property, birth or other status” (UNDP 2012, p.5). This implies that anti-corruption programmes need to be designed in a way that includes all groups, and data needs to be collected with a special focus on those who are most disadvantaged.

Participation and inclusion

“Every person and all peoples are entitled to active, free and meaningful participation in, contribution to, and enjoyment of civil, economic, social, cultural and political development” (UNDP 2012, p.5). Anti-corruption programmes should therefore include mechanisms that allow for participation of all groups affected by the decision-making process. This includes guaranteeing access to information and may require capacity building for civil society in order to ensure meaningful participation.

Accountability and rule of law

Stakeholders need to be accountable for the results of their programmes. In a human rights framework, this is expanded to grounding those responsibilities in a framework of entitlements and corresponding obligations. Therefore, stakeholders need to identify who is affected by the issue (rights-holders), who needs to act on it (duty-bearers) and the capacities. For example, capacities may be needed to collect and analyse disaggregated data or to conduct impact assessments and policy or budget analyses. (UNDP 2012)

Interestingly, three of these principles are central both to anti-corruption and human rights: i) participation; ii) transparency and; iii) accountability. However, as can be seen in the discussion above, they are operationalised differently. In addition, the core principle of non-discrimination is not frequently used in anti-corruption even though it is closely related. Therefore, before attempting any mainstreaming efforts, there needs to be an agreement on the definitions of the concepts used (ICHRP 2010).

Human rights standards

Human rights standards, which are reflected in the human rights treaties, are binding upon countries which ratified the treaties and therefore should help to define the objectives of any anti-corruption programme and policy. The standards strengthen the assessment and analysis and create certain conditions for the implementing and monitoring phases (OHCHR 2006).

Availability

“Facilities, goods and services need to be available in sufficient quantity and equipped with what they require to function” (UNDP 2012, p.5). In anti-corruption programming, this can, for example, ensure that complaints mechanisms are available in all regions.

Accessibility

This refers to both physical and economic accessibility of facilities, goods and services for all, especially vulnerable or marginalised groups.

Importantly, in the context of anti-corruption, “they must also be affordable and poorer households must not be disproportionately burdened by expenses. This also requires the removal of administrative barriers that can prevent the poor from accessing facilities, goods and services” (UNDP 2012).

Quality

“Facilities, goods and services need to be relevant, culturally appropriate and of good quality” (UNDP 2012).

Human rights in the project cycle

A human rights based approach to anti-corruption needs to ensure that the realisation of human rights is mainstreamed throughout the project cycle.

Assessment and analysis

As with gender mainstreaming, this stage of the project/programme cycle requires a detailed analysis. The aim is to identify rights-holders and the corresponding human rights obligations of duty-bearers as well as the immediate, underlying, and structural causes of the non-realisation of rights. The human rights focus can benefit the situational analysis in multiple ways. It can help to identify groups that lack rights as well as groups that might deny rights to others and therefore can highlight root causes that make populations vulnerable to corruption. Hence, it adds a different look at social and political processes and the functioning of institutions, which is a fundamental component for anti-corruption measures too. Overall, a human rights based analysis can show gaps in the capacity of legislation, policies, voice and institutions (OHCHR 2006).

An HRBA, according to OHCHR (2006), makes situation analysis stronger in three ways:

- Causality analysis: drawing attention to root causes of development problems and systemic patterns of discrimination.

- Role/obligation analysis: helping to define who owes what obligations to whom, especially with regard to the root causes identified.

- Identifying the interventions needed to build rights-holders’ capacities and improve duty-bearers’ performance

Only very limited information is available on how to apply this approach to anti-corruption interventions, and additional research would be needed to provide guidance on how to use this approach for anti-corruption interventions. This would be an important initial step to understand the relationship between human rights and corruption and prevent the possible negative impacts of combining human rights and anti‑corruption programmes mentioned above. This also would also benefit corruption research, as little data is available that has been disaggregated by gender or poverty, for example.

A report by ICHRP (2010) discusses using a human rights based approach for the collection of data and concludes that focusing on the connection between corruption, discrimination, gender bias and poverty would create better targeted anti-corruption programmes and tools. UNDP and Global Integrity (2008) give a structured guide to creating new indicators that should be measured in an incremental fashion, which is a useful guideline for creating measures and indicators for corruption and human rights.

Planning and design

A human rights based approach also has benefits for the planning and design phase of a policy or programme. Since, under an HRBA, the policy or programme should help to realise human rights, programming should be informed by the recommendations of international human rights bodies and mechanisms. Programme objectives should be “geared towards, and articulated as, the positive and sustained changes in the lives of people necessary for the cull enjoyment of a human right or rights” (OHCHR 2006). This approach can help to prioritise groups that should be targeted. Based on the initial assessment of the capacity of rights-holders to claim their rights, and of duty-bearers to fulfil their obligations, strategies can be developed to build these capacities.

UNICEF Finland (2015) identifies seven steps for human rights based programme planning:

- Situation analysis: project planning starts with getting clarity on the exact problem that the project seeks to address from a human rights perspective and the reasons behind them.

- Causality analysis: helps identify multiple causes of unfulfillment of a specific human right in a particular context, together with a list of candidate rights-holders and duty-bearers.

- Role pattern analysis: identifies or confirms the exact individuals or groups of people who have claims concerning the problem, its causes, and unfulfilled rights.

- Capacity gap analysis: identifies obstacles that the rights-holders have in claiming their rights as well as the duty-bearers’ capacity gaps in meeting their obligations. It looks at a number of components such as responsibility, authority, resources, and decision making, and communication capabilities of rights-holders and duty-bearers.

- Identification of candidate strategies and action: identifies candidate actions that are likely to contribute to the reduction or closing of the capacity gaps of rights-holders and duty-bearers.

- Partnership analysis: identifies the key actors working with the same problem(s) in the intervention area and to find out what their focus areas and strengths are.

- Project design: priority actions should be clustered into a specific project, with clearly articulated project objectives, targets and outcomes.

All of these steps should be done with rights‑holders and duty-bearers. Only if human rights principles have been applied throughout the planning process can mainstreaming human rights be successful.

Implementation

Duty-bearers and rights-holders need to be involved throughout the implementation phase. Additionally, an essential focus of the implementation strategy is on empowering rights‑holders and strengthening the obligations of the duty-bearers to protect and guarantee those rights. Last but not least, the implementation phase needs to focus on the meaningful participation of all affected by the policy (OHCHR 2006)

Monitoring and evaluation

Programmes should monitor and evaluate outcomes and processes guided by human rights standards and principles. As for gender mainstreaming, both qualitative and quantitative indicators, selected based on the human rights standards, should be used to monitor the project outcomes. OHCHR (2006) recommends that three clusters of national level indicators could be used: structural, process and outcome indicators. Structural indicators look at the information on the legal and institutional framework for the realisation of the human right. Process indicators consider specific milestone outcomes that lead to the progressive realisation of human rights, and outcome indicators look at the overall information on the realisation of a human right (OHCHR 2006 p. 30).

Conclusion

The importance of mainstreaming gender into anti-corruption has been well established to ensure that men and women are benefitting equally from anti-corruption programmes and that these programmes do not have any unintended gendered consequences. While, less has been discussed on mainstreaming human rights into anti-corruption programmes the two agendas can mutually benefit from each other.

Mainstreaming both gender and human rights requires that the two are taken into account at every step of the programme cycle, from assessment to analysis to planning and design and monitoring and evaluation. Overall mainstreaming these aspects into anti-corruption activities means that the differences between men and women and different groups need to be acknowledged and that the differential impacts of interventions on men and women and on human rights need to be considered in any activity. Importantly when using a human rights based approach, it is important that agencies consider that all anti-corruption efforts should also ensure the realisation of human rights and not only the fight against corruption. The mainstreaming of gender and human rights into anti-corruption therefore requires a more nuanced look at the all possible human implications of interventions and detailed considerations throughout the entire programme cycle of how interventions affect different groups and their enjoyment of human rights.