Query

Please provide a summary of the latest developments on corruption and anti-corruption efforts in Sierra Leone, including the main sectors affected by it.

Background

Since the end of the decade long civil war in Sierra Leone, the country has appeared to make significant progress in its path towards democracy. Democratic elections were held in 1996, 2002, 2007, 2012, 2018 and 2023. In the past few years, however, concerns have started to emerge regarding state-led weakening of political institutions sustaining democracy.

The country’s first election took place in February and March 1996, marking the beginning of a democratic transition that returned multiparty politics to the country after almost 30 years of one-party rule under the APC party, and a four-year military junta under the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC) (Wai 2015). The 2018 election even led to alternating power between the government and opposition (European Union 2021).

With the return of elections came attempts to address high levels of corruption, including the creation of an anti-corruption agency in 2000, and the domestication of international anti-corruption frameworks and laws. Since 2005, there have been four iterations of the government’s anti-corruption strategy, which usually relies on a three-pronged approach of enforcement, prevention and education, with a focus on public sector corruption and its impact on public governance (Anti-Corruption Commission 2019). More recently, in 2019, a special anti-corruption court was established, making Sierra Leone one of few countries with a special judicial division to handle corruption related cases.

In the past few years, these legal and institutional efforts to control corruption have been accompanied by strong anti-corruption rhetoric. The president’s anti-corruption message took centre stage during his inauguration. However, despite the rhetoric and legal and institutional reforms, some of the government’s actions send mixed signals in terms of how genuine the government’s commitment to anti-corruption really is. In late 2021, for instance, the government suspended Auditor General Lara Taylor-Pearce just weeks before her office was expected to report on a major government audit. Two years after her removal, no evidence of impropriety has been put forward by the committee set up for this purpose (Freedom House, 2023; Sierra Leone Telegraph 2023).

Furthermore, despite the many legal and institutional changes, the 2023 Freedom House report still gives the country the lowest possible score (one out of four) when assessing safeguards against official corruption (Freedom House 2023).

Also of concern are indications that the political institutions and processes sustaining democracy may be weakening and that some democratic gains made over past decades could be fading away as a result of the expansion of executive powers, electoral manipulation and growing restrictions on civic space. Allegations of vote manipulation and statistical inconsistencies in the 2023 presidential election are a worrying example of this democratic backsliding (European Union Election Observation Mission Sierra Leone 2023).

There are also troubling signs about civic space and media freedom in the country. While “most media outlets are free of direct control by politicians, … many media are influenced by politicians in practice because of a lack of financial resources or poor management” (Reporters Without Borders 2023). Furthermore, “journalists are free to investigate all subjects, including politically sensitive ones, but they often find it hard to obtain information about public institutions” (Reporters Without Borders 2023). Harassment and intimidation by the police and online threats to journalists also remain common in the country (Reporters Without Borders 2023).

This complex background helps us understand why corruption remains a challenge in the country. In the following sections, this Helpdesk Answer will delve deeper into these issues, provide an overview of the nature of corruption in Sierra Leone, its forms, extent and effects on the sectors most affected by it, as well as an overview of the legal and institutional arrangements currently in place to prevent, detect and prosecute corruption. This analysis contributes to the understanding of corruption and governance in the Sierra Leone and underlines the role that corruption may play as one of the drivers of popular discontent and the backsliding of democracy that appears to be taking place in the country.

Extent of corruption

Successive governments since the end of the civil war in 2002 have made efforts to tackle corruption and prosecute alleged acts of corruption by previous governments, but the extent to which these efforts are yielding result is not obvious. While the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) has increased the number of corruption investigations, it often fails to indict the most senior officials and instead charges lower-level officials (US Department of State 2020). Media and opposition party members have also questioned the ACC’s objectivity and independence (US Department of State 2022). The country’s anti-corruption agency admits in its national anticorruption strategy (NACS) 2019-2023 that “corruption is all pervasive and deeply entrenched, and mostly socially accepted as a norm and inevitable” (Anti-Corruption Commission 2019).

It is worth noting that there is a shortage of data on corruption and anti-corruption in the country. Most of the indicators available are composite metrics of perceptions, expert assessments on the quality of legislation, and population surveys. While the first two types of data are usually updated on a regular basis, the high cost of surveys makes it difficult to keep statistics on direct experiences of bribery and corruption up to date. The result is that some of the most important indicators, including the ones required to report progress against the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals in the area of corruption, have not been updated since 2019.

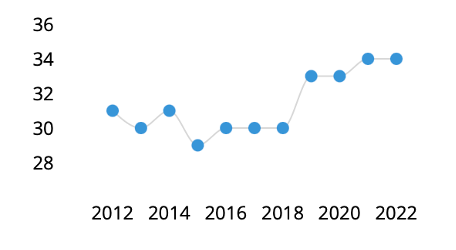

Sierra Leone’s low score on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) seems to corroborate that corruption is widespread in the country: Sierra Leone’s score has oscillated between a minimum score of 29 in the 2015 edition, and a maximum score of 34 in the 2022 (see Figure 1) (Chêne 2010; Sierra Leone Telegraph, 2022; Transparency International, 2023b). It is worth noting, however, that this slight improvement in score is not deemed statistically significant by Transparency International, which means that there is disagreement among the sources on the direction in which the country is moving. For this reason, the organisation catalogues the country’s score as stagnant since 2012, which differs from the government’s interpretation of the results.

To put the CPI score into perspective, Sierra Leone ranks in the 40th percentile of the CPI, its score is only slightly above the regional average (32), but still lower than the global average (43) (Transparency International 2023b).

Figure 1. Corruption Perceptions Index score for Sierra Leone (2012-2022)

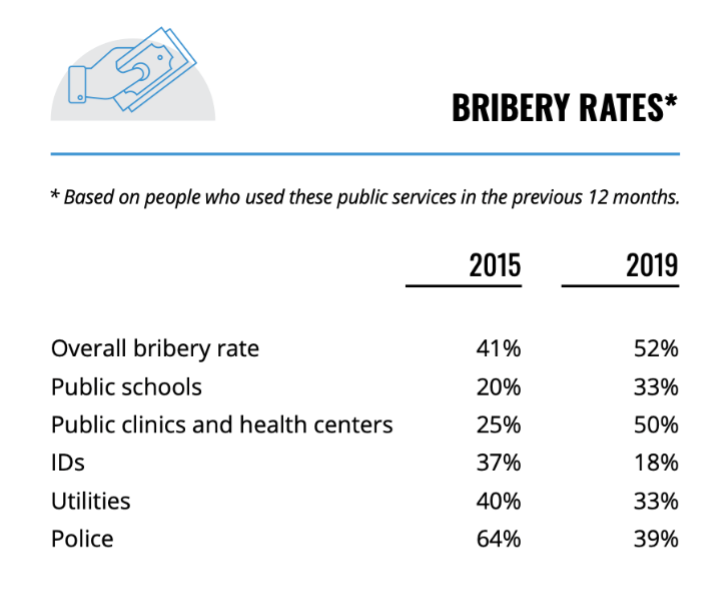

Data from the latest Global Corruption Barometer also shows the high incidence of corruption in Sierra Leone: 52% of the people who had contact with a public service in the 12 months prior to the survey reported having to pay bribes to receive the service they needed (Transparency International 2023b). The high levels of bribery were common across all the services included in the survey: 51% paid a bribe to access medical care, 39% bribed a police officer and 33% relied on bribery to access public schools (see Figure 2). It is also worth noting that 43% of survey respondents perceived corruption levels to be increasing (Pring and Vrushi 2019). At the same time, however, the perception of corruption in the presidency has declined compared to 2012, but so has the people’s trust in government (Afrobarometer 2023a).

Figure 2. Bribery rates by service in Sierra Leone

These seemingly contradictory survey results capture the complexity of the corruption landscape in the country: on the one hand, the government has successfully passed some relevant anti-corruption laws, created institutions with the mandate to curb corruption and the strong anti-corruption rhetoric of the past few years might have convinced some citizens that there is a real commitment to change; on the other hand, bribery remains common and there is evidence to suggest that there are still important loopholes in the national legislation, and that that enforcement of existing frameworks remains a challenge.

Sierra Leone is still lagging behind when it comes to transparency and access to information. The Transparency Index, which measures both de jure and de facto transparency, shows a big gap between what is established in the law and what transparency looks like in practice. Sierra Leone reaches a perfect score when it comes to evaluating formal transparency commitments, but it only receives 5.5 out of 14 points in the de facto components (ERCAS 2021). Some of the information that appears not to be available online for the public includes, among others, the current government expenditures, politicians’ financial and conflict of interest disclosures, supreme court hearing schedules, the land cadastre and building permits in the capital city. The Index of Public Integrity (IPI) also shows that the country is largely lagging behind in terms of administrative transparency and the availability of online services. The overall score is 4.2 out of 10 indicating a below average performance. Most importantly, the indicators show that opportunities for corruption outweigh the constraints (ERCAS 2021).

In addition to the transparency gaps, the institutional checks and balances that help keep democratic governments in check and ensure accountability are not yet well established in this young electoral democracy. As a result, the legislature and the judiciary are not altogether effective in exercising oversight and control over the executive. The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, which measures the effectiveness of judicial and legislative checks and balances on the executive, shows that government powers are not effectively limited by the judiciary (World Justice Project 2023). Furthermore, constraints on the government powers have slightly weakened since 2015.

According to the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index, the judiciary in Sierra Leone “is not in the position to counter the executive and keep it in check. Judges, among them the members of the supreme court, are appointed by the president, following proposals made by the Judicial and Legal Service Commission, whose members are appointed by the president and judges. The positions of the attorney general and the minister of justice are combined in a single individual, blurring the lines between powers” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022). Widespread corruption and a lack of human and material resources limit the effectiveness of the judicial system at all levels.

Considering the weakening democratic checks and the insufficient levels of transparency and access to government information, it is unsurprising that bribery and petty corruption is not the only form of corruption in the country. Instances of grand corruption have been widely documented. In March 2020, for example, a commission of inquiry set up by President Bio’s governance transition team presented the results of an audit that revealed that hundreds of millions of dollars were lost to corruption over a 10-year period. The 110 persons of interest and their collaborators included “former high-ranking government officials, among them ex-president Koroma, the vice president, ministers of state and heads of departments, agencies and parastatals” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022).

The following section considers in more depth the different types of corruption and their specific manifestations in Sierra Leone.

Forms of corruption

Corruption in Sierra Leone has many forms and types, but, in this analysis, a classification in line with established typology will be adopted in terms of size, style of manifestation, and actor (Bussell 2015).

Petty corruption

Petty corruption is widespread and the most common of all the types in Sierra Leone. The fourth national anti-corruption strategy recognised this problem with stakeholders’ agreeing that it permeates all arms of government (Anti-Corruption Commission 2019).

A review of the 95 convictions achieved by the ACC between 2000 and 2018 shows that over 90 percent of the convictions are petty corruption by nature (Anti-Corruption Commission 2023). Most of the convicted cases were soliciting/accepting advantage, peddling influence, breach of procurement procedures, misappropriation of funds or donor fund mismanagement. The higher conviction rates for petty corruption, however, do not mean that grand corruption or cases involving large sums and powerful actors do not occur. The low proportion of grand corruption cases is more a result of their higher degree of complexity, with cases more likely to take longer to investigate and prosecute.

The use of bribery to access public services is common in Sierra Leone. As mentioned before, more than half of the people who come into contact with the authorities to access one of the five public services covered by the Global Corruption Barometer paid a bribe to obtain the service (Pring and Vrushi 2019).

How petty corruption manifests, however, tends to vary across sectors. In the health sector, for example, bribes are often requested to access medical care. Women in labour have reported being victims of extortion by medical staff to receive care and proper monitoring by nurses (Mitchell 2017). Shortages of personnel, low salaries, the retention of pay or requests to work for free in exchange for permanent employment in the future, create incentives for bribery and other forms of petty corruption in healthcare (Mitchell 2017; Onwujekwe et al. 2018).

In addition to bribery, the mismanagement of funds, including development aid contributions, and diversion of relief materials have been widely documented (Dupuy and Divjak 2015). An audit of the Ebola fund, for example, showed several irregularities, duplicated and undocumented payments for supplies or transfers of funds to private individuals private individuals rather than to organisations (Dupuy and Divjak 2015).

Data published by Afrobarometer shows that an overwhelming majority of citizens (75%) say that the government handled the COVID-19 pandemic better than the Ebola outbreak, and 91% think the government did a good job handling the latest pandemic. Despite these positive results, only 6% of survey respondents report having benefitted from the government’s relief assistance and over 60% think that the resources were unfairly distributed. Furthermore, four in ten Sierra Leoneans (43%) thought that at least some of the resources intended for the COVID-19 response were lost to corruption (Afrobarometer 2023b).

In other sectors, such as education, bribes are also common to secure admissions to secondary school. The phenomenon is so common that, in 2022, the minister of education warned against bribery in admissions ahead of the academic year about to begin (Jalloh 2022).

Grand corruption

In addition to petty corruption, grand corruption is also a problem in Sierra Leone. Large scale embezzlement or misappropriation of public funds, for example, have been widely documented. A leaked 2019 auditor general report found evidence of massive misappropriation and mismanagement of public funds worth more than US$100 million (Sierra Leone Telegraph 2020). In 2018, a former vice president, Victor Foh, was charged for public fund mismanagement and embezzlement of funds related to a pilgrimage fund (Al Jazeera, 2018). Similarly, a former minister of mines, Mansaray Minkailu, was charged by the ACC for allegations relating to selling mining stakes at artificially low prices to the nephew of President Bio (Al Jazeera 2018).

In June 2023, the UK Serious Fraud Office (SFO) charged the chief executive officer, chief financial officer and an international business consultant of London Mining Plc, an international mining company, for conspiring to make multiple corrupt payments to secure preferential treatment by the government in Sierra Leone (Serious Fraud Office 2023). Collusion has been particularly visible in the exploitation of natural resources, mainly in the diamond mining industry (Frankfurter et al. 2018). A study by Transparency International also documented how collusion between business and government resulted in entire communities and hundreds of people being scammed out of their land (Transparency International 2019). In the Kono district, for example, a web of collusion between chiefs, government officials and mining companies, has been documented against the backdrop of allegations of land grabbing, and predatory exploitation of diamonds (Frankfurter et al. 2018; Transparency International 2019).

Although the “domestic political system is formally democratically legitimized, … patronage, clientelism and nepotism as social mechanisms play an important role in decision-making processes and policy implementation” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022). Corrupt networks also appear to have captured large parts of the public administration and perpetuate a system of political patronage and access to state funds. Recruitment for government positions, for example, is commonly based on kinship and nepotism (Acemoglu et al. 2016). A report in 2007 found widespread evidence of ghost workers in the public administration and flagged that there were no records for 60% of civil servants and that of the 236 senior public servants on the payroll, fewer than half (125) were found to be at their posts (International Crisis Group 2008; Acemoglu et al. 2016).

Main sectors affected by corruption

This section discusses corruption in sectors, focusing on those sectors identified as important contributors to corruption in existing literature. The sectors covered are health, natural resources, education, the public sector and the police.

Health

The health sector ranks among the most corrupt in Sierra Leone. Several studies show how corruption contributes significantly to poor health outcomes (Anderson and Beresford 2016; Onwujekwe et al. 2019).

Corruption is a significant barrier to the uptake of public health insurance scheme (HIS) as it decreases participation in the HIS and the willingness to pay for it (Jofre-Bonet, Kamara and Mesnard 2023). During the Ebola epidemic, a study found corruption to be partly responsible for the higher fatality rate and severity of outbreaks (Dupuy and Divjak 2015). As mentioned before, the COVID-19 pandemic was widely perceived to be better managed, but large section of the population still thought that corruption affected at least some of the funds intended to handle the crisis and that funds were unfairly distributed (Afrobarometer 2023b).

A recent Afrobarometer report shows that healthcare is considered one of Sierra Leoneans’ top priorities for government action (Sanny 2020). This is because healthcare is difficult to access and bribe requests are common. The poor and less-educated are particularly likely to be extorted to access care (Onwujekwe et al. 2019; Jofre-Bonet, Kamara and Mesnard 2023). Four out of 10 Sierra Leoneans (41%) cited health among the top three most important problems facing the country that government should address, and 50% of Sierra Leoneans who sought medical care at a public health facility in the previous year said they had to “pay a bribe, give a gift, or do a favour” at least once to obtain the care they needed (Pring and Vrushi 2019).

Bribery is not the only form of corruption affecting healthcare. Other practices identified in the literature include absenteeism and theft of drugs and supplies (Mitchell 2017). Mammy Koker, a Krio slang used to describe the practice of secretly taking paid jobs during working hours has also been documented in the sector (Institute for Governance Reform 2018). During the COVID-19 pandemic government officials were also caught selling fake COVID-19 vaccination cards to non-vaccinated individuals (Sierra Leone Telegraph 2021).

Education

Corruption contributes to poor education outcomes in Sierra Leone (Kirya 2019). Some of the well-documented examples of corruption in education include:

- the diversion of school funds and procurement fraud, which rob schools of necessary resources to improve infrastructure;

- nepotism and favouritism in personnel hiring, which lead to the employment of underqualified teachers;

- admission and examination fraud, which disincentivises learning;

- the sale of books and supplies meant to be handed out for free, which often means that the least privileged groups in society might end up having to abandon their education (CHRDI 2017).

The 2015 auditor general report, for example, revealed various payment and procurement irregularities in this sector. For instance, cash withdrawals totalling Le3,517,199,967, (US$180,000) were made in the name of Ministry of Education staff instead of suppliers or service providers (CHRDI, 2017). “Contrary to standard accounting procedure, which provides that payments should be made directly to the suppliers or beneficiaries, withdrawals for sums totalling Le425,000,000 and Le282,081,800 respectively were made by staff of the Ministry of Education” (CHRDI, 2017). Admission frauds were also common in which school and university officials received bribes in exchange for admission or charged higher unauthorised fees, forcing students to drop out.

Examination fraud is also common. This is an arrangement in which examiners receive bribes from students in exchange for the answers to the test. According to diverse accounts, this is big business in Sierra Leone, controlled and managed by organised criminals working closely with teachers and targeting some of the country’s under-resourced schools (Sierra Leone Telegraph 2017). In the 2020 West Africa Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE), 4,270 examination malpractices were recorded with collusion between examiners and students, constituting over 60% of the reported cases (Kebbie 2022).

Extractive sector

When weak political institutions meet an abundance of natural resources, the opportunities to extract rents and divert funds from the local economy increase (Robinson et al. 2006). Corruption is thus often cited as one of the main reasons why resource-rich economies fail to transform the profits from the sector into better economic and social outcomes (Kolstod and Wiig 2009 and Assadi 2013). Given the extractive sector’s propensity to corruption (see OECD 2016; Transparency International 2019; Serious Fraud Office 2023), transparency is a key to reduce the opportunities for predation (Kolstod and Wiig 2009).

In the case of Sierra Leone, natural resources contribute up to 67% of total exports. Transparency in the sector is thus of particular importance since a lack thereof can make corruption less risky and more attractive, make it harder to use incentives to make public officials act cleanly and select the most honest and efficient people for public sector positions or as contract partners (Robinson et al. 2006). Additionally, in the absence of transparency, asymmetrical information may give some actors undue advantage over others and cooperation tends to be harder to sustain over time as opportunities for rent-seeking arise (Robinson et al. 2006).

For the case of Sierra Leone, fostering transparency as a way to prevent corruption may also have implications for the overall stability in the country given the role that natural resources played in sustaining the civil war between 1991 and 2002 (EITI 2022).

In 2018, President Bio committed to use the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) as a tool for reform to improve the country’s investment climate and included a target to mainstream transparency and accountability practices into the extractive sector, in the Medium-Term National Development Plan 2019–2023 (EITI 2022).

Despite the efforts and commitments to mainstream transparency, corruption remains a reality in the sector. Corruption allegations have been raised in relation to land acquisitions, especially for mining, in the Kono district (InsightShare 2018; Transparency International 2019; Anti-Corruption Commission 2022).

The huge potential gains from mining and natural resource extraction combined with the high levels of corruption in government provide incentives for foreign companies to rely on corrupt means to secure access to the country’s natural wealth. Private sector and multinational firms have thus remained prominent actors in the corruption schemes associated with the sector. As mentioned earlier, senior officials from a multinational mining company were found guilty of conspiring to make multiple corrupt payments to secure preferential treatment by the government in Sierra Leone (Serious Fraud Office 2023).

It is worth highlighting, however, that while transparency is important to prevent corruption in the extractive sector, the impact of transparency alone may be limited if other conditions are not present to ensure that those who engage in corruption or other illegal activity can be held accountable (Kostad and Wiig 2009). It is thus important to consider necessary reforms in other institutions that help contain corruption to ensure that transparency measures fulfil their promise.

Informality in the mining sector could also pose a risk for corruption. Small-scale and informal miners, also known as artisanal miners, are common in many low-income countries. In Sierra Leone, artisanal mining accounts for up to 40% of mining production and employs over 300,000 people (Artisanal Mining Policy 2018). The lack of regulation and improper monitoring of these activities, however, leave the sector vulnerable to illegal extraction. It has been estimated that more than 50% of Sierra Leone’s diamonds are smuggled out of the country through suspicious deals that involve artisanal miners, intermediaries and officials (OCCRP 2022). Lost revenue and illicit movements of funds arising from extractive activities were estimated to reach US$558 million per annum between 2006 and 2016 (Frankfurter et al. 2018).

Public administration

Corruption in public administration is a central challenge in Sierra Leone and has historical roots. While corruption is seen as widespread in the country, the public sector is perceived to be the epicentre of the problem. Given the high levels of bribery reported across sectors, it is unsurprising that individuals with fewer interactions with the public sector tend to experience less corruption than those with frequent encounters with officials (Jofre-Bonet, Kamara and Mesnard 2023).

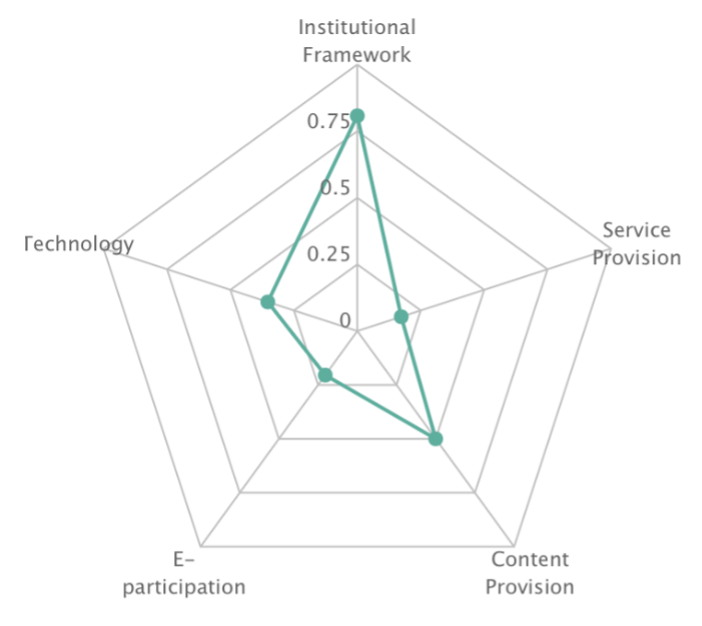

The low levels of administrative transparency and e-government services constitute significant obstacles for controlling corruption in public administration in Sierra Leone. According to the Index of Public Integrity, the country is among the lowest scoring countries in these two categories (ERCAS 2023). The United Nations e-government survey 2022 confirms this trend. Despite being seen as having a strong institutional framework for e-government, Sierra Leone’s public sector seems to be lagging behind when it comes to technology availability, content and service provision, and e-participation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. United Nations Online Service Index

It is worth noting that, even though technology can serve as a deterrent for corruption in public administration by simply eliminating direct contact between citizens and public servants, the low levels of access to the internet in Sierra Leone constitutes a further obstacle to the anti-corruption potential of such technologies (ERCAS 2023).

Police

As explained by Transparency International in its analysis of the CPI 2022 results, high levels of corruption in the policelead citizens to mistrust the institution. This can result in the public reporting less crime and a reduced willingness to assist the police in countering crime. Police corruption can thus lead to higher crime rates and lower crime clearance rates. Of particular concern is police collusion with organised criminals, which can take many forms, including tip-offs, active involvement in human, drug or arms trafficking or even contract killing (Martinez B. Kukutschka 2023)

The Sierra Leone Police Force is perceived by the public as the most corrupt public institution, according to the Anti-Corruption Commission (N’Gobie 2021). As shown in Figure 2, the police are also the second-most likely institution to extract bribes from the public, only after the healthcare sector. Other studies seem to support this result. According to a study from Institute for Governance Reforms “Nearly three in five drivers said they pay bribes when stopped by the police” (AYV News 2020).

While bribery might be the most visible form of corruption, collusion between police forces and organised crime is of particular concern. The ACC has documented cases of collusion in which police officers receive kickbacks from criminals, including gangs, drug dealers and operators of illegal businesses such as brothels, in exchange for protecting business and revenue streams from law enforcement (N’Gobie 2021). This can lead to a situation where organised crime and other illegal activities thrive (Martinez B. Kukutschka 2023). It is, therefore, unsurprising that Sierra Leone’s resilience against organised crime is rated as low by the Global Organized Crime Index.

Legal anti-corruption framework

International conventions and initiatives

There have been major institutional reforms targeted at curbing corruption, but these have done little to change the informal norms and values that support and explain corrupt acts. This section discusses the legal and institutional frameworks.

The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC)

The United Nations Convention against Corruption is the only legally binding universal anti-corruption instrument. The UNCAC convention was adopted by a UN General Assembly resolution in 2003 and was ratified by Sierra Leone a year later. The convention requires the establishment of a range of offences associated with corruption and devotes a separate chapter to its prevention. It also attaches importance to strengthening international cooperation to counter corruption (Transparency International Sierra Leone 2013).

In 2009, the UNCAC Conference of State Parties adopted Resolution 3/1 to install a review mechanism to evaluate the implementation of the convention by different state parties. So far, Sierra Leone has undergone two implementation reviews.

The latest review, which was published in 2019, identified successes including: the deployment of an anti-corruption toolkit to support ministries, departments and agencies; the setting up of integrity management committees in all ministries, departments and agencies to facilitate reporting by public officials; and the establishment of a commission to oversee the implementation of the right to access information act. The challenges identified include the need for constitutional level empowerment for the ACC to: aid their financial, institutional and operational independence; identify all public functions with high vulnerability to corruption; and set up a system of rotation of such positions, establishing an e-procurement system and making the National Public Procurement Authority guidelines mandatory (UNODC 2019)

African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption

Sierra Leone is a party to the African Union Convention on Prevention and Combating Corruption. The convention has 28 articles, and the key objective is to “promote and strengthen the development in Africa by each State Party mechanisms required to prevent, detect, punish and eradicate corruption and related offences in the public and private sectors”. The convention entered into force on 5 August 2006 (African Union 2019).

The convention covers different aspects of corruption, ranging from transparency and accountability in public financial management, to bank secrecy, international cooperation and the coordination of legal assistance (African Union 2019).

ECOWAS Protocol on the Fight Against Corruption

The protocol on the fight against corruption was signed in Dakar on 21 December 2001 and adopted by heads of state and governments.

The protocol “provides for preventive measures in the public and private sectors. These include requirements in the public service of declarations of assets and establishment of codes of conduct. Also included are requirements of access to information, whistle-blower protection, procurement standards, transparency in the funding of political parties and civil society participation and many other requirements. It is also required to establish, maintain, and strengthen independent national anti- corruption authorities” (Transparency International 2006 p.33).

Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures act

Sierra Leone has a comprehensive legal framework and robust institutional structure to investigate and prosecute money laundering. The law is the Anti-Money Laundering Act 2012, which criminalises money laundering and related activities. It has been considered strong and recognised as standard for anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF) (GIABA, 2020).

There is also a money laundering regulation which applies to financial institutions regulated by the Bank of Sierra Leone (UNODC no date). There are four agencies involved with the investigation and prosecution of money laundering cases, namely the Sierra Leone Police, the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), the National Revenue Authority, and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (UNODC no date). Sierra Leone has been part of the mutual evaluation system of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The evaluation report shows that Sierra Leone has a 50% technical compliance with the FATF recommendations, but very low effectiveness (GIABA 2020). Going by the Basel AML index, Sierra Leone has high ML/TF vulnerability, as the country scores 6.9 in 1o, though this is a measure of country institutional ML/TF capability rather than actual money laundering activity (Basel AML Index, 2022).

Domestic legal and regulatory frameworks

The Anti-Corruption Act 2000

The major corruption focused law is the Anti-Corruption Act passed by parliament in 2000. The act establishes the Anti-Corruption Commission, the main anti-corruption agency in Sierra Leone. The ACC has been amended in 2008 and 2019 to correct shortcomings including the commission’s lack of prosecutorial powers and with uniform minimum sentencing penalties (Kanu 2016). The lack of prosecutorial power was considered a major weakness of the ACC prior to the 2008 amendment. Before the amendment, the ACC relied on an external committee to make decisions as to whom to prosecute (Kanu 2016).

The Right to Access Information Act, 2013

This law is the main piece of freedom of information legislation in the country. The law was passed in 2013 as an act to provide for the disclosure of information held by public authorities or by persons providing services for them and other related matters (Sierra Leone Government 2013). The law listed the mechanism to access government information including the process, fees and exempted information.

The act was followed with the establishment of the Right to Access Information Commission (RAIC) in 2014 (Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data 2022). The implementation of the act and the RAIC have not been evaluated and there are no assessments of their effect and impact on corruption, but these laws generated lots of enthusiasm from the demand side of the process, including citizens and development partners like the Open Government Partnership.

The national anti-corruption strategy

The key document setting out the government's anti-corruption policy is the national anti-corruption strategy. Section 5(1) (c) of the Anti-Corruption Act of 2008 confers in the commissioner the power to “coordinate the implementation of the National Anti-Corruption Strategy” (Anti-Corruption Commission 2019).

Since 2000, the country has implemented three national anti-corruption strategies (2005 -2008, 2008-13, 2014-2019). These strategies are intended to capture the government’s resolve to confront corruption using an integrated and a well-coordinated approach (Anti-Corruption Commission, 2019).

Institutional anti-corruption framework

Anti-Corruption Commission

The ACC was established in 2000 by an act of parliament (ACA 2000) in recognition of the need to counter corruption in Sierra Leone (Anti-Corruption Commission 2019; UNODC no date). The establishment coincided with the global anti-corruption movement and push, especially from the international development community, for good governance in developing countries. The commission was established to take the lead in the prevention, eradication or suppression of corruption and corrupt practices.

The ACA 2000 was amended in 2008 due to notable shortcomings, including the commission’s lack of prosecutorial powers (Kanu 2016). The commission was further empowered to investigate any act of corruption as well as examine and retain all declarations of assets required, especially by public officials.

The establishment of this commission as well as the act is significant for Sierra Leone because, prior to the passing of the ACA 2000, the only legislation in effect for corruption related offences was the Prevention of Corruption Ordinance 1907 (Kanu 2016). The ordinance, a two-pager, was obsolete and proved to be fundamentally inadequate to address corruption and its pervasive practices (Kanu 2016). The ACC act has been amended to further empower it and bring it in line as expected in conventions and frameworks like the African Union Convention on Prevention and Combating Corruption (Kanu 2016). A judicial division has also been set up to fast-track corruption cases.

The ACC has successfully investigated and prosecuted corruption allegations in different parts of the government and has dealt with cases ranging from misappropriation of donor and public funds to soliciting or peddling advantage (Anti-Corruption Commission 2018). In 2019 alone the ACC “indicted and charged 31 persons, convicted nine individuals, and recovered more than three billion leones ($300,000) from corrupt government officials excluding court fines and other assets” (US Department of State 2020) and, more recently, the ACC also recovered “187 million leones (US$14,400) in a case against mayor of Freetown, for alleged inappropriate use of Freetown City Council funds” (US Department of State 2022).

Media, civil society and opposition partieshave questioned the ACC’s objectivity and independence.Some observers have also suggested that the agency’s work is highly politicised and targets mostly opposition politicians, such as the mayor of Freetown, but fails to investigate credible allegations of corruption against the ruling president and members of the ruling party (US Department of State 2022).

Anti-Corruption Division of the High Court

Sierra Leone is one of the 27 countries that has a special judicial body with a focus on corruption cases (Schütte 2022). The Anti-Corruption Division of the High Court was established pursuant to a constitutional instrument promulgated in April 2019. The court is mandated to hear and determine all anti-corruption matters instituted by the ACC and act as a model court for criminal cases to confront the traditional challenges in the criminal justice system. These include undue delays in proceedings, limited courtrooms and integrity deficit among some administrative staff (Christian Aid 2020). An evaluative analysis shows a significant increase in judicial proceedings and a general increase in the frequency of sittings and the conclusion of interlocutory applications (Christian Aid 2020).

The Office of the Auditor General

The auditor general office was created by an act of parliament in 1998. It is essentially meant to ensure value for money for public funds and has the responsibility of auditing the public accounts of Sierra Leone and its institutions as well as enterprises set up partly or wholly from public funds (UNODC no date).

The independence of the office has been put into question by the removal of the auditor general in 2021. Her removal has been argued to be connected to the publication of evidence showing mismanagement and misappropriation of public funds across various government ministries (Sierra Leone Telegraph 2023).

The office of the ombudsman

The office of the ombudsman was established by Act No. 2 of 1997 with a mandate to investigate any action taken or omitted to be taken in the exercise of the administrative functions of any department, government agency, statutory corporation or institution set up with public funds (UNODC no date). It works closely with the ACC. It has no judicial powers and has been referring cases for investigation and sharing resources with the ACC.

National Public Procurement Authority (NPPA)

The NPPA was created by an act of parliament in 2004 in recognition of the need to standardise and regulate public procurement (UNODC no date). The NPPA regulates and monitors public procurement in Sierra Leone and advises the government on issues related to public procurement. A standard procurement system helps the government save money, contributes towards curbing corruption and improves governance.

Other stakeholders

Domestic legal and regulatory frameworks

Media and civil society are important components of the normative constraints on corruption (Mungiu-Pippidi 2013). In Sierra Leone, freedom of association and organisation is constitutionally guaranteed, and there are several non-governmental organisations operating in the country. However, new regulations introduced in 2018 require the renewal of registrations for NGOs and ministerial approval for projects (Freedom House 2023). This is considered restrictive and an obstruction of civic space. According to Civicus, which monitors civic space freedom globally, the Sierra Leone civic space is classed as obstructed, with a score of 46 out of 100 (Civicus 2023).

The media landscape is generally free and media freedom is legally guaranteed. Sierra Leone has a score of 2 out of 4 in the Freedom House ranking of media freedom (Freedom House 2023). There are many independent newspapers circulating freely, and a good number of public and private radio and television outlets. In July 2020, parliament introduced the independent media commission act and repealed part v of the 1965 public order act, which in essence criminalised libel and sedition and were criticised as laws to target journalists (Freedom House 2023).

Despite the relatively open space for media, Reporters Without Borders note several issues that challenge the media’s ability to act as an effective anti-corruption watchdog, including limited public sector transparency and informal control of the media by politicians due to lack of funding, and poor management (Reporters Without Borders 2023).

Conclusion

Corruption remains a significant challenge in Sierra Leone. The country ranking in the CPI shows a positive, albeit statistically insignificant trend, but the experiential reality seems not to have changed much, as shown by other indicators. This presents a conundrum as there have been major anti-corruption efforts from both domestic and international actors.

While governments over the past decade have recognised the importance of curbing corruption, most of their efforts have focused on legal and institutional reforms. Anti-corruption laws and frameworks are well established and regularly amended. A special anti-corruption judicial division, which exists in only a few countries, has also been set up. Low levels of transparency, poor access to information amid a poor digital environment, the politicisation of key institutions, and the weakness of the existing democratic checks on government, however, remain some of the greatest obstacles to counter corruption in the country.