Query

Please provide an overview of the evidence concerning international fraud operations as these relate to corruption. What, if any, overlap is there between corruption and private sector fraud? To what extent are anti-corruption measures and anti-money laundering safeguards relevant to efforts to tackle fraud.

Background

In the most comprehensive sense, fraud includes any crime for gain that uses deception as its principle modus operandus. More specifically, “fraud is a knowing misrepresentation of the truth or concealment of a material fact to induce another to act to his or her detriment” (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners 2020a). Thus, according to this definition, fraud includes any intentional or deliberate act to deprive another of property or money by guile, deception or other unfair means (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners 2020a). Simply put, fraud is the offence of intentionally deceiving someone to gain an unfair or illegal advantage (financial, political or otherwise) (Transparency International 2020a).

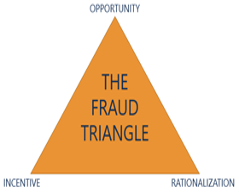

Developed by Dr Donald Cressey, a criminologist whose research focused on embezzlers (people he termed “trust violators”), the fraud triangle theory is the most extensively used for explaining why people commit fraud (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners 2020a).

The fraud triangle has three components: i) opportunity, circumstances that allow fraud to occur; ii) incentive, alternatively called pressure/motivation and refers to an individual’s mindset towards committing fraud; and iii) rationalisation, an individual’s justification for committing fraud (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners 2020b).

Types of fraud include:

- Internal fraud: also calledoccupational fraud, which can be defined as “the use of one’s occupation for personal enrichment through the deliberate misuse or misapplication of the organization’s resources or assets”. This type of fraud occurs when an employee, manager or executive commits fraud against his or her employer.

- External fraud: this covers a broad range of schemes including but not limited to dishonest vendors engaging in bid-rigging schemes, billing the company for goods or services not provided, or demanding bribes from employees. Similarly, consumers submitting bad checks or falsified account information for payment or attempting to return stolen or knocked-off products for a refund. In addition, organisations also face threats of security breaches and thefts of intellectual property perpetrated by unknown third parties. Other examples of frauds committed by external third parties include hacking, theft of proprietary information, tax fraud, bankruptcy fraud, insurance fraud, healthcare fraud and loan fraud.

- Fraud against individuals: these include identity theft, Ponzi schemes, phishing schemes and advanced-fee frauds.

An extended understanding of (accountancy) fraud was proposed by Trompeter et al. (2013) by adding three elements to the triangle: the act of fraud, its concealment and the resulting ‘conversion’ (the benefit to the fraudsters) (Driel 2018). Such an expanded view results in four domains of fraudulent behaviour: individual, firm, organisational field, and society at large (Driel 2018).

Corruption, on the other hand, is defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. Corruption may involve the commission of a variety of acts defined as criminal, such as bribery, extortion, graft, embezzlement, including various forms of fraud (Kratcoski and Edelbacher 2018).

Despite explicit definitions, the two terms are often used interchangeably, while having some distinct differences as well as similarities (Moiseienko and Izenman 2019). In line with the understanding of corruption as “abuse of entrusted power for private gain”, it is those who hold a position of power in an organisation that can be engaged in corruption (Transparency International 2020a). By this definition, various instances of internal and external fraud that involve the abuse of power link the phenomenon with corruption. For example, the involvement of insiders in facilitating complex “external” fraud, especially in the financial sector, may be viewed as corruption-enabled fraud (Moiseienko and Izenman 2019). Moreover, the process of conducting fraud might involve corruption; for example, fraud gives rise to “dirty money” which needs to be laundered, involving corrupt actors and systems (Kepler and Schneider 2018).

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has created fertile ground for fraud and corruption to thrive (Deloitte Switzerland 2020). The availability of public funding coupled with lax due diligence introduces new possibilities for fraud and corruption, and several international organisations and enforcement agencies have begun to sound the alarm about this rising risk (Bonucci et al. 2020). A recent survey by KPMG in Australia found that 7% of executives said they had already seen fraudulent or corrupt behaviour that they would attribute to the COVID-19 era working conditions. And an overwhelming 83% believed their organisation was vulnerable to fraud taking place now (KPMG Australia 2020).

Fraud and corruption aimed at the public sector

The terms fraud and corruption are often used interchangeably in the context of the public sector. This can be attributed to the fact that many forms of public corruption are regarded as frauds against public coffers (Levi 2012: 48). Kingsley (2015) defines corruption and fraud in the public sector as “gargantuan twin brothers” with fraud classified as a form of corruption. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (2013) also identified corruption as one of the ten most common types of fraud in healthcare provider fraud schemes. These examples show that the two crimes are closely related.

Fraud within government and state-owned enterprises usually involves more internal than external perpetrators, as evidenced by the PwC Global Economic Crime Survey which noted that government entities around the globe that had suffered from economic crime reported that 57% of perpetrators were internal while only 37% were external (PwC 2011: 8). According to the survey, government and state-owned enterprises reported that 69% of the fraud they had suffered was related to the misappropriation of assets (embezzlement), with 22% of fraud related to bribery and corruption (PwC 2011: 6). This means that external actors may need to rely on internal actors to be successful in their fraudulent schemes, and corruption may be used to enable such cooperation.

Transnational organised fraudsters have targeted value-added tax (VAT) fraud schemes, particularly in Europe (Europol 2015; Cooper 2018). Usually, fraudsters use corruption to minimise law enforcement or operational risks by public officials (Levi 2008: 392; Levi 2012: 45). This includes bribery or collusion with tax officials to facilitate VAT fraud through the use of fictitious companies to fraudulently claim tax refunds, using fake receipts to claim tax refunds for real companies or fraudulently claiming VAT refunds for non-exported goods or services (Zuleta 2008). In Hungary, a whistleblower disclosed that organised criminal groups engaged in VAT fraud schemes were receiving assistance in their illegal operations from corrupt officials within the tax authority (OCCRP 2013).

One of the biggest European fraud scandals in recent years involved the carbon tax fraud scheme totalling €1.6 billion (King 2018). The international fraud scheme took advantage of a weakness in the European Union’s carbon trading scheme to buy VAT-free credits from abroad and then sell them on the French market with the added sales tax, which they did not pay back to the French government (King 2018). To minimise detection and get a warning of forthcoming arrests, the organised criminal scheme invited a police official to their parties, transferred money into his bank account and offered him trips to Morocco (King 2018).

Public procurement is another target for organised fraud groups (Levi 2008: 391). For instance, INTERPOL reported a sophisticated international scheme during the ongoing pandemic which defrauded German health authorities in the procurement of €15 million worth of face masks through compromised emails of legitimate companies and the quick laundering of the proceeds of the advance payment (INTERPOL 2020). An investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) discovered that people with ties to political leaders and linked to organised crime and corruption in Romania were involved in the public procurement of face masks (Poenariu 2020). Hence, international procurement fraud schemes may involve the bribery of public employees by the fraudsters to secure the tender and to pay a fraudulent invoice or falsified expenses (PwC 2015).

The public is also targeted by international fraudsters who use misconceptions or stereotypes of corruption in regions such as Africa to their advantage in fraud schemes (Smith 2009: 9). For example, the 419 scammers in Nigeria take advantage of the corruption stereotypes in the country to send email scams claiming, for example, that they need to transfer large amounts of money from deceased corrupt leaders to the targets of the fraud (Levi 2008: 393). In other emails, they claim to be in possession of large deposits of money from a country perceived to be corrupt and they need to transfer the money to the targets of fraud for safekeeping.

One of the email scams purported to come from a member of the Nigerian Department of Petroleum Resources’ contracts award panel. In the email, which proposed to deposit US$31 million from an over-invoiced contract, the following was written, reflecting stereotypes: “Here in my country there is great economic and political disarray and thus looting and corruption is rampant and the order of the day, thus explaining why you might have heard stories of how money is being taken out of Nigeria, this is because everyone is making desperate attempts to secure his or her future, so that when we retire from active service we do not languish in poverty” (Smith 2009: 9). When the victim responds to the scam email, they are persuaded to pay “advance fees” to remove “blockages” (part of the fraud scheme) for the transfer of the funds or are lured to another country where they are scammed to pay more money before the completion of the “promised” large transfer (Levi 2008: 393).

Proceeds of fraud may be used to buy influence from corrupt high-level officials. For instance, Roberto Lee Vesco, a renowned international fraudster in the 1970s who had been accused by the US Securities and Exchange Commission of defrauding investors of around US$224 million, made illegal contributions to the re-election campaign of former US President Richard Nixon in 1972 (Jackson and Brook 1995). In this situation, proceeds of the fraud could have been used as part of the illegal contribution, as a way to influence corruptible people who could offer him protection from other governments and creditors judicially pursuing him (Levi 2008: 401).

Fraud has deleterious effects on the public. It directly affects vulnerable and disadvantaged citizens who rely on essential public services, which the government cannot deliver as a result of the fraudulent diversion of the resources (International Public Sector Fraud Forum 2020a: 9). Targeted victims suffer a loss of their hard-earned savings, which worsens their socio-economic conditions. Also, it causes traumatic experiences for victims and their families, resulting in social problems, trauma and mental health issues (International Public Sector Fraud Forum 2020a: 9). A combination of fraud and corruption may further lead to an erosion of public trust in government and a loss of international and economic reputation (International Public Sector Fraud Forum 2020b).

Organised fraud operations may also compromise national security and community safety, particularly where such fraud is linked to terrorist financing or when the proceeds are used to expand criminal activities (International Public Sector Fraud Forum 2020a: 24; Levi 2012: 44).

Overlap between corruption and private sector fraud

A paper based on a review of the scale and nature of transnational organised crime’s infiltration of the private sector found that fraud, extortion and corruption (in the forms of money laundering and asset misappropriation) make up large parts of the crimes being done either to private sector organisations, or through them (Cartwright and Bones 2017).

The private sector is the target of fraud or asset theft, particularly in construction, consumer goods (US$460 billion counterfeit goods) and financial card fraud. They also unwittingly facilitate crime; for example, through the real estate sector laundering dirty funds or the transport industry moving illicit goods (Cartwright and Bones 2017). The paper by the Global Initiative against Transnational Crime also notes that the impact of transnational organised crime on the private sector, through fraud and corruption, is growing not shrinking, with effects of such crimes disproportionately affecting the Global South043b9c5336fe (Cartwright and Bones 2017).

Private sector fraud and corruption overlap when it comes to white-collar crimes. Since no universally accepted definition of the term exists, such crimes typically encompass the following offences committed mainly by corporations, their owners, executives or employees as well as by government or municipal officials: fraud, corruption, embezzlement, misappropriation and malfeasance, tax fraud, intellectual property theft, insider trading, money laundering, Ponzi schemes, misrepresentation of financial statements, price-fixing, illegal cartels, and collusion as well as the breach of environmental, health and safety regulations (Berghoff and Spiekermann 2018). These forms of corporate crime typically result from actions of several individuals in cooperation, using fraudulent and corrupt means (Gottschalk 2018).

According to a Norwegian database, 405 convicted white-collar criminals in the country contain 68 offenders (17%) who committed financial crime on behalf of the organisation. White-collar crime represents violations of integrity as well as a failure to comply with moral standards, as in the example of corruption managed by Siemens in Germany (Gottschalk 2018). The US financial crisis of 2007–2009 was also attributed in part to widespread fraud and corruption, and most of the largest mortgage originators and mortgage-backed securities issuers and underwriters were implicated in regulatory settlements, paying multibillion‑dollar penalties (Fligstein and Roehrkasse 2015).

In 2014, an international scheme of influence was unearthed for peddling, embezzlement, tax evasion, illegal campaign funds and corruption involving a diverse range of actors and sectors of society, mainly in Portugal and Brazil (Barlyng 2019). The fraud design revolved around public officials, up to the highest level of government, rewarding construction companies with state tender contracts, and around the selling, buying and merging of state and privately owned telecommunication companies. A big Portuguese financial institution then funnelled and laundered money from Portugal and Brazil, which eventually led to the collapse of the bank in question, Banco Espirito Santo. Tracing the money led investigators to European, Latin American and African countries (Barlyng 2019).

Another case highlighting the overlap of private sector fraud and corruption was the Volkswagen (VW) scandal of 2015, where VW had intentionally manipulated diesel emission tests in approximately 11 million cars worldwide (470,000 in the United States). Illegal software was installed for years in its car models, which lowered harmful emissions of nitrogen compounds under test conditions. Without such a “defeat device” from the test runs, VW engines emitted pollutants up to 40 times above what was legal in the US. The scam allowed VW to systematically inflate financial gains at the expense of the environment and public health (Jolly 2019). In 2018, VW agreed to pay more than €1 billion in fines in Germany and in the Netherlands for obtaining unfair economic advantages (Barlyng 2019). A corrupt corporate culture at VW was highlighted as an explanation for the scandal occurring (Menzel and Murphy 2017).

Professional enablers of fraud operations

Bankers, real estate agents, notaries, lawyers, accountants and corporate service providers are gatekeepers of the financial system, with anti-money laundering (AML) obligations to protect financial markets against criminals (FATF 2012). While their primary obligations include shutting down criminals, such as fraudsters, from entering the financial systems by conducting customer due diligence (FATF 2010: 44), they may willingly, complicity or negligently overlook these obligations, which can result in them performing services for fraudsters such as:

- setting up anonymous companies or other legal structures to run the fraud schemes

- providing nominee services to companies and other legal structures

- assisting or permitting fraudsters to open onshore or offshore (sometimes anonymous) banks accounts to move dirty money

- assisting or permitting fraudsters to invest their ill-gotten gains, for example, via real estate or other luxury goods purchases

- failing to identify and report suspicious transactions, making it easy for fraudsters to engage in fraud, corruption and money laundering

Evidence shows that these professionals are often involved in fraudulent schemes. The UK’s national lead on economic crime pointed out that some accountants and lawyers were “complicit” or “complacent” in money laundering and were eroding public trust in their professions (Hymas 2019). The FBI has recently referred to hedge funds in financial institutions that “have been used to facilitate transactions in support of fraud, transnational organized crime, and sanctions evasion” (FBI 2020: 2).

In the US, an attorney allegedly helped OneCoin engineers (led by “crypto queen” Ruja Ignatova) to launder US$400 million to the British Virgin Islands (Redman 2020). Ignatova claimed she had invented a cryptocurrency to rival Bitcoin, and persuaded investors to invest billions before disappearing in 2017 (BBC News 2019). This case highlights the links between international fraud operations and the involvement of lawyers as professional enablers of such operations.

A criminal organisation engaged in VAT fraud across Europe had a network of more than 100 companies, mostly offshore, in different European countries and in the US (Europol 2018). The proceeds of fraud were layered in the network of companies before being moved to bank accounts, with the criminal group laundering more than €140 million in two years (Europol 2018). The establishment of such a scheme would require the services of professionals, such as lawyers, corporate service providers and bankers.

According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), proceeds from VAT fraud schemes are usually laundered through international banking systems, and fraudsters use the same offshore banks in countries such as the UK (FATF 2007: 4). A case study on UK VAT carousel fraud that cost £36 million between 1996 and 1998 showed that illicit proceeds were spent on properties, boats, luxury cars and casinos (FATF 2007: 7). This means that professionals, such as bankers, real estate agents, lawyers, casinos and car sales people, knowingly or negligently failed to dictate or report fraudulent transactions, which allowed fraudsters to use their services.

Recently, a Nigerian social media star Ramon Olorunwa Abbas, also known as Ray Hushpuppi, appeared before a US court charged with running an international fraud scheme (Akinwotu 2020). He allegedly conspired to launder hundreds of millions of dollars through business email compromises, fraud schemes and other scams, and used the proceeds of his fraudulent operations to buy luxury cars, clothes and watches, and to charter jets which he showcased on his social media accounts (Dawkins 2020). In this case, professionals, including bank personnel, real estate agents, jewellery shops personnel and car dealers failed to identify and report suspicious transactions, making it easy for the alleged fraudsters to engage in fraud and money laundering.

Connection between fraud and money laundering

Money laundering is the processing of criminal proceeds (dirty money) through which a person or a company hides the true origin, nature and ownership of their profits so that they appear to have originated from legitimate sources (FATF 2019). Anti-money laundering (AML) efforts aim to stifle the financial flows linked to such criminal activity (Chêne 2017).

Money laundering usually involves a complex series of transactions, working at three stages: placement, layering and integration (SAS 2020):

- Placementrefers to how and where illegally obtained funds are placed. Money is often placed via: payments to cash-based businesses; payments for false invoices; “smurfing”, which means putting small amounts of money (below the AML threshold) into bank accounts or credit cards; moving money into trusts and offshore companies that hide beneficial owners’ identities; using foreign bank accounts; and aborting transactions shortly after funds are lodged with a lawyer or accountant.

- Layeringrefers to severing criminal funds from their source. It involves converting the illicit proceeds into another form and creating complex layers of financial transactions to disguise the funds’ origin and ownership. Criminals do this to obscure the trail of their illicit funds so it will be hard for AML investigators to trace the transactions.

- Integrationrefers to the re-entry of the laundered funds into the economy in what appears to be normal, legitimate business or personal transactions. This is sometimes done by investing in real estate or luxury assets. It gives launderers and criminals an opportunity to increase their wealth.

Money laundering and fraud are connected in the sense that criminals who commit fraud eventually need to monetise that information and launder the proceeds so that funds appear legitimate. As such, the success of a fraud operation is usually contingent, in its final stages, on money-laundering activities and vectors.

The overlaps in the criminal context between fraud and money laundering may be understood in the following ways:

Money mules and shell companies

Money mules (also called smurfers), wittingly or unwittingly, transfer stolen funds between accounts, often in different countries, on behalf of others (EUROPOL 2020). Witting mules are individuals who are hired to accept dirty cash, keep a portion as commission, and then transfer that money abroad (usually via wire transfer). To recruit potential money mules, criminals will often use fake job advertisements or create social media posts about opportunities to make money quickly (EUROPOL 2020).

An unwitting money mule is an individual whose accounts are used in the same fashion but with the difference that they do not know the money is the proceeds of crime (FBI 2019). These individuals are usually scammed into doing this, for example, by applying for a work from home position or as victim of a romance scam (FBI 2019; EUROPOL 2020).

Shell companies are often used to launder money, evade taxes and perpetuate all manner of fraud, acting as a more permanent way station for ill-gotten proceeds (Hubbs 2014).

The Zeus Trojan case serves as a prominent example for the use of unwitting money mules. It was a global bank fraud scheme that used malware to steal and then launder millions of dollars. In 2010, the Manhattan US attorney charged 37 defendants in 21 separate cases. Cyber-attacks, targeting small businesses and municipalities in the US, were unleashed via a “benign” email sent to victims. The email, in the form of a trojan, installed malware recording every keystroke once the link was clicked on. Once the fraudsters recorded the victim’s bank logins, they would take control of the accounts and transfer thousands of dollars to different accounts set up by money mules.

Individuals who entered the US on student visas were targeted as money mules and provided with fake foreign passports and instructions to open false-name accounts at US-based banks. Once the bank accounts were opened, the wire transfers were deposited into these accounts, and the mules transferred the money overseas (after keeping a small commission), or they withdrew cash to be bulk smuggled out of the country. Over US$3 million was stolen and laundered, all as the result of an “innocent” email that generated malware (Toth 2019).

Digital currency

It is usual for cybercriminals and threat actors to exchange value for goods and services as both digital currency as cybercrime is carried out on the internet. Although not all digital currency in today’s economy is dirty money, as there are both legitimate and illegitimate uses of this form of currency, they remain an important conduit for moving the proceeds of fraud (Toth 2014). One example of digital currency misuse in laundering the proceeds of fraud was a video gaming currency investigation. Gaming currency (or video game currency) is generated by players achieving certain levels or completing various tasks within a video game.

In 2018, a case emerged wherein subjects reverse-engineered a video game (the cyber event) to fraudulently generate a large amount of in-game currency (the fraud). Once the in-game currency was generated, the subjects transferred that value off the account and converted it into currency to be wired to various corporations offshore. From there, the money would be wired to individuals (money mules), who would then withdraw it in cash and continue the laundering cycle. In the end, this scheme generated over US$17 million in proceeds, which were used towards cash holdings and expensive assets (Toth 2019). Another case was that of OneCoin, which relied on enablers to launder the proceeds of a fraud operation focusing on a fake cryptocurrency scheme (Redman 2020).

Money transfer services and wire transfer

This is the most common technique used for money laundering proceeds from cybercrime. Traditional conduits like Western Union or MoneyGram are used. With low fees, a global network and lax AML compliance mechanisms, such platforms often provide a sense of anonymity for criminals (Toth 2019).

To detect and prevent fraud and financial crime, many institutions draw a distinction between the two. Generally, financial crime includes money laundering and other criminal acts, including bribery and tax evasion, involving the use of financial services to support criminal enterprises. It is most often addressed as a compliance issue. Fraud, however, is viewed as a host of crimes, such as forgery, credit scams and insider threats, involving the deception of personnel or services to commit theft.

Wire transfers through the conventional financial system may also be initiated or misdirected based on fraud and are fast and efficient ways to layer funds abroad (UNODC 2013).

Role of anti-corruption and anti-money laundering safeguards in tackling fraud

Anti-money laundering safeguards

Several practices exist to reduce and eradicate money laundering, including procedures that ensure strict adherence by financial institutions to anti-money laundering rules. The advent of financial cybercrime has eroded these distinctions, leading financial institutions to use many of the same tools to protect their assets. These countermeasures centre around: i) identifying and authenticating the customer; ii) monitoring and detecting transaction and behavioural anomalies; and iii) responding to mitigate risks (Hasham et al. 2019).

Indicative of the overlaps in criminal activity, many of these safeguards may be transposed and may also be applied to the international fraud context.

Know your client (customer identification procedures)

Financial institutions and professionals ought to demand proper customer identification and verification to ensure legitimacy. Higher risk products and services (e.g. private banking) require more in-depth documentation (SAS 2020). This will assist in identifying or detecting fraudsters who may want to use their services to set up fraud schemes or to launder their proceeds.

Suspicious transaction report (STR)/suspicious activity report (SAR)

According to the FATF Recommendations, a suspicious transaction report (STR) or a suspicious activity report (SAR) should be filed by a financial institution or designated non-financial businesses and professions to relevant authorities if they have reasonable grounds to believe that a transaction is related to criminal activity (Low 2017). Establishing clear and efficient reporting mechanisms will ensure that reported cases are attended and resolved in a timely manner.

Lists of sanctioned individuals

Various regulatory bodies such as the US Treasury Department, US Office of Foreign Assets Control, the United Nations, the European Union, Her Majesty’s Treasury and the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering have requirements for financial institutions to check transaction parties against lists of sanctioned individuals, companies, institutions and countries (SAS 2020). This helps to keep sanctioned fraudsters from accessing financial services.

Registers of beneficial ownership

Anonymous (shell or phantom) companies disguise the identity of their true owner, the person (or people) who ultimately controls or profits from the company. These people are also known as the beneficial owners (BOs). The fix to this problem, countries make publicly available the registers of beneficial owners of companies, trusts, and other legal entities that are registered within their borders (FTC 2020). Without anonymity in legal persons and legal arrangements, fraudsters will not be able to hide their true identity behind corporate vehicles used in fraud schemes. Professional enablers should also check BO information.

Other AML measures

There are various pieces of legislation governing AML aspects of fraud in various national and international jurisdictions – US: Patriot Act and Bank Secrecy Act; Canada: Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA); Australia: Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act of 2006. A few other international directives or guidelines include:

- Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament of 20 May 2015 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing. The European Union agreed to an updated anti-money laundering directive (2018) that would create national-level registers of beneficial ownership information throughout the union, though they would only be fully available to government authorities. Members of the public must pass a “legitimate interest” test to gain access to the information for trusts; however, for companies, the register must be made publicly available (EUR-Lex 2020a; FTC 2020). Such registers make it harder for the proceeds of fraud to be put into anonymous shell companies, and assist law enforcement authorities to readily uncover the identities of the real owners of companies (Ljubas 2019).

- Directive (EU) 2018/843 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending directive (EU) 2015/849 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, and amending directives 2009/138/EC and 2013/36/EU. Acting as an update of to the 2015 directive, the 2018 directive, among other things, highlights the importance of financial intelligence units (FIUs) in identifying criminal networks and calls for an “integrated approach on the compliance of national AML/CFT regimes with the requirements at union level, by taking into consideration an effectiveness assessment of national regimes” (EUR-Lex 2020b).

- The FATF Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach to Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers of 2019 expands the scope of rules on AML to virtual transactions and to a broad range of providers of crypto-related products and services, including but not limited to custodians and exchanges. They help national authorities understand and develop regulatory and supervisory responses to virtual assets activities as well as assisting the private virtual assets sector in understanding and complying with their AML/CFT obligations (FATF 2019). Implementing the measures will assist in the detection or prevention of virtual fraudsters; for instance, those involved in cryptocurrency.

Anti-corruption safeguards

Directive (EU) 2017/1371 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2017 on the fight against fraud to the union's financial interests by means of criminal law (EUR-Lex 2020) enhances law enforcement measures on corruption and fraud. For instance, article 3 provides an obligation for member states to ensure that fraud affecting the union’s financial interests (for example, VAT and procurement schemes) constitutes a criminal offence, thereby strengthening criminalisation of fraud-related activities in the regime. Furthermore, Article 4(2) criminalises passive and active corruption related to these fraud schemes affecting the union’s financial interests. According to article 8, where fraud or corruption harming the EU’s financial interest is committed within a criminal organisation, this shall be considered to be an aggravating circumstance.

As explained in the paper, public officials may accept bribes from international fraudsters to enable their schemes. Hence, existing anti-corruption legislation prohibiting bribery and other forms of corruption by public officials may assist in curbing fraud (articles 11-25 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption). Enhancement of law enforcement may deter public officials from accepting bribes, kickbacks or engaging in any other corrupt activities with fraudsters.

Education or awareness programmes on anti-corruption and anti-bribery for employees (public and private) and the public may equip them to prevent, identify, deter and address fraud and corruption (International Public Sector Fraud Forum 2020b: 9). For instance, articles 7(1)(d) of the United Nations Convention against Corruption provide for training programmes for public officials to enhance their awareness of the risks of corruption inherent in the performance of their functions. Such outreach training may provide vital information to potential victims or collaborators in fraud schemes to become aware of corruption or fraud schemes they are exposed to and how to communicate with relevant agencies.

- Technology fraud in the private sector is found to be driven from eastern and southern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East (Cartwright and Bones 2017).