Query

Please summarise the evidence on the lessons learned on how to undergo institutional strengthening of AML systems in fragile states.

Caveat

Anti-money laundering is often grouped with combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT), including by the IMF, World Bank and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Nevertheless, as the IMF itself has stated, “while ML and TF share common attributes and exploit the same vulnerabilities in financial systems, they are distinct concepts and present different risks” and that they should be assessed separately (IMF 2023: 8). This paper focuses on strengthening robust AML systems, rather than CFT.

Introduction

Fragility is a multidimensional phenomenon, commonly associated with weak institutions, poor governance, economic inequality, social tensions and political instability. These underlying characteristics can result in low limits of public service delivery, high levels of corruption, violent conflict and significant vulnerabilities to natural disasters (OECD 2022).

Fragile settings also create fertile ground for illicit economic activity, such as the criminal activities that constitute the predicate offences for money laundering (such as human trafficking, illicit natural resource extraction, drug production and trafficking, among others) (OECD 2018b: 1).

The structural composition of the economy in many fragile states may further enhance money laundering and terrorism financing risks. Many fragile states have large informal sectors in which the majority of transactions are cash based. This informality and reliance on physical cash transactions pose challenges because they can operate outside the regulatory oversight of any AML/CFT institution, and generally allow for greater anonymity, making it easier for illicit funds to enter the legitimate financial system without detection (Passas 2015).

International efforts to counter money laundering and terrorism financing have led to the establishment of international standards and best practices. The most prominent is the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The FATF was established in 1989 to promote the implementation of measures to counter money laundering, terrorist financing and other types of illicit finance, such as proliferation financing (FATF 2023). The FATF sets international standards through its recommendations and oversees the implementation of its standards in member countries through mutual evaluation reports (MERs).

Over the last couple of decades, most countries have adopted AML regimes that – at least on paper – align with the FATF Recommendations. The FATF mutual evaluation review process has played a role in improving technical compliance by highlighting non-cooperative countries and establishing a clearly delineated mechanism for evaluating compliance through its recommendations (Chêne 2017: 3). There is some empirical support for the idea that this translates into better outcomes; in a study of 67 developing countries, Combes et al. (2019) found that countries that are more compliant with the FATF Recommendations mobilise more domestic tax revenue than countries that are less compliant with the FATF Recommendations.

However, while there has been progress on technical compliance (i.e. legal alignment with the FATF Recommendations), the effective enforcement and implementation of AML/CFT measures has been much more limited (Chêne 2017: 3).

This indicates that, although the FATF framework provides a robust foundation to tackle money laundering and terrorism financing, the implementation of these standards poses significant challenges in practice (Durner & Cotter 2018: 3).

An AML regime is a highly complex institutional setup that requires coordination between numerous agencies and cooperation between the public and private sector (Goredema 2011: 4-5). Even advanced economies can struggle to enforce legislation designed to curb financial crime, as illustrated by the fact that four of the five most high-profile money laundering scandals identified by Sanctions Scanner (n.d. a). have connections to the United States, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Belgium

This “implementation gap” is particularly severe in fragile and conflict-affected states, as they face unique challenges in implementing and enforcing standardised AML measures (Passas 2015: 1).

Particularly in contexts where the de-jure state has limited authority over its territory, the systems meant to oversee and regulate economic transactions often lack capacity and/or are compromised or captured by elites (Passas 2015: 11). Frequent political, social, environmental or economic upheaval may limit the resources available to build and maintain robust AML institutional frameworks, while state capture and high levels of corruption may undermine the effectiveness of AML measures (OECD 2018b: 108; FACTI Panel 2021: 33).

These challenges are evident with reference to the Basel Institute on Governance’s AML Index (2023) which lists jurisdictions with the highest money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) risks. These countries are consistently the same as those countries considered to be fragile states; Haiti, Chad, Myanmar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo have the highest scores on the index (Basel Institute on Governance 2023). Cross-referencing the Basel AML Index with the Fragile States Index reveals that most of the countries on the Basel Index with a score of over 7 are also labelled “alert”, “high alert” or “very high alert” on the Fragile States Index (Fund for Peace 2023: 7).

Therefore, while adhering to the FATF standards is becoming increasingly important for integration into the global financial system, the dynamic and complex nature of FATF's Recommendations can be overwhelming for countries with limited capacity. The FATF process has been critiqued as a formal tick-box exercise with excessive focus on technical compliance rather than actual efficacy in countering illicit financial flows (IFFs)cad364217e82 (Durner & Cotter 2018: 3), a process over which low-income countries have limited influence in shaping (Maslen 2023). Critics such as Brandt (2023) note that the “current evidence on anti-IFF policies [is] based exclusively on information from high-income countries”, while the FATF itself has stated “the FATF standards presume a level of formality in the economy” (FATF 2008: 5).

Possibly in response to this criticism, the FATF introduced a new evaluation methodology in 2013, which places more emphasis on practical implementation and effectiveness (Chêne 2017: 3). Increasingly, countries are encouraged to not only establish legal frameworks and institutions but also demonstrate that there are mechanisms for enforcing these laws that can prevent and counter money laundering and terrorism financing. For instance, the FATF has introduced immediate outcomes as part of its evaluation methodology to assess the effectiveness of a country’s AML/CFT efforts, emphasising the real-world impact of policies and actions (Durner & Cotter 2018: 4).

Despite the widespread recognition in the literature on state-building that establishing robust formal institutions is insufficient by itself to overcome fragility (Boege et al. 2008; Menkhaus 2010; Eriksen 2010; Kaplan 2008), development economists have shown how the quality of institutions are nonetheless an important determinant of inclusive development (Acemoğlu and Robinson 2012 ; Rodrik et al. 2002).

Yet development interventions intended to strengthen state capability in fragile states have a mixed record of success. Pritchett et al. (2012: 2) point out two key issues. The first is that these interventions are often premised on dysfunctional bureaucracies in aid-recipient states adopting specific institutional models that characterise highly resilient functional states. Secondly, even where the type of intervention does suit the context, state capability building can go awry when nascent institutions are given responsibilities that they are not (yet) capable of handling (Pritchett et al 2012: 2). These practices result in a “capability trap”, where the appearance of development masks the lack of functional progress.

As such, there are clear challenges to externally supported attempts to build the capacity of formal institutions in fragile settings. Yet in the domain of AML/CFT, Umar et al. (2020: 3) observe that the most effective strategies to prevent illicit financial flows in developing countries draw on external technical assistance and capacity building initiatives to complement internal reform efforts to regulate trade, enhance beneficial ownership transparency, establish automatic exchange of information agreements with other countries and comply with the FATF Recommendations.

The question therefore arises: how can development agencies best support efforts to establish robust AML systems in fragile settings to reduce the circulation of dirty money in these societies and the associated negative impacts?

Challenges of AML/CFT in fragile states

Corruption within financial and supervisory institutions

Corruption itself poses a significant risk to the integrity and effectiveness of a national AML/CFT institutional infrastructure. Key institutions on both the public and private side of the AML/CFT infrastructure (such as banks and entities responsible for reporting suspicious transactions as well as financial intelligence units and law enforcement) can be compromised by or indeed part of corrupt networks. In such cases, financial intermediaries and their clients may engage in collusive arrangements, making it challenging to detect and address money laundering activities.

The problem can be particularly pronounced in fragile states, in which maintaining political power relies on monopolising access to state resources, the ability to distribute rents to key constituencies and rigging the system to maintain exclusive access (Chigas 2023). The OECD (2018b: 109) states that in West Africa,

“key figures in business and government can serve as pivotal nodes in the networks that perpetuate criminal behaviour, initiating or organising transactions domestically and with international markets, protecting flows from seizure and network members from prosecution, and laundering money through legitimate business or international trade”.

In countries affected by state capture, limited investigative capacity or a lack of independence in key AML/CFT institutions makes it difficult to counter such arrangements (FACTI Panel 2021: 33; Goredema 2011: 8).

Reprisals and political interference

In contexts where there is a significant risk of reprisal or where the business sector is heavily dominated by a few customers, financial institutions, such as banks, may be hesitant to file suspicious activity reports (SARs) due to fear of potential loss of major clients or facing political backlash. Additionally, in states with networks of patronage linking state institutions, ruling political parties and businesses, there can be risks involved in reporting on politically exposed persons (PEPs) due to potential repercussions from powerful individuals (Goredema 2011: 8).

In fact, in settings marked by a weak rule of law, strong centralised authority may instrumentalise law enforcement and oversight agencies, including those responsible for AML, to target political opponents. These state organs may even become a conduit for the diversion of resources and other corrupting abuses of power (OECD 2018a: 24).

Capacity and resource constraints

Even in cases where there is political will to tackle ML and TF, low capacity in relevant institutions often remains a significant problem. State authorities in fragile settings typically have limited resources that are already stretched across various policy priorities, many of which may seem more pressing than tackling dirty money. Moreover, in fragile contexts, the state is likely to lack the resources to monitor and regulate all economic sectors and both financial and physical flows (Goredema 2011: 11; FATF 2008: 4).

Dominant cash-based informal sector

Besides capacity limitations, one of the most cited difficulties in implementing a robust AML/CFT regime in fragile states are their predominantly cash-based economies and the fact that the informal sector often outsizes the formal economy. In such settings, financial transactions are extremely difficult to monitor (FATF 2008: 5).

Particularly in cash-based economies, where anonymity is easier to maintain, financial institutions face difficulties in accessing information about the origins of the funds they handle. The lack of official, reliable information can make it challenging for financial intermediaries to identify whether a client's financial activities are illicit, which can hinder the ability to file accurate SARs (Goredema 2011: 9).

Difficulties in verifying ultimate beneficial owners

Many countries affected by fragility lack robust and verifiable personal identification and physical address systems. This can complicate the verification of ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs), without which both basic and enhanced due diligence can be difficult. This may result in inadequate SARs. As such, limited identification systems hinder the ability of financial institutions to accurately apply customer due diligence (CDD)/know your customer (KYC) procedures and track the ultimate beneficiaries of transactions (Goredema 2011: 8; FATF 2008: 5).

Lack of coordination between anti-corruption, AML/CFT and law enforcement institutions

Effective collaboration between anti-corruption institutions (such as anti-corruption agencies) and AML bodies (such as financial intelligence units) is crucial to curb financial crime. Yet, even if these institutions are operational, their mandates, resources and expertise can be spread across a multitude of organisations from the intelligence, law enforcement and security sector communities.

The absence of a well-defined structure delineating the mandates, responsibilities and standard operating procedures of different agencies can lead to inefficient and siloed approaches, making the investigation and prosecution of corruption and money laundering problematic (Goredema 2011: 10).

Limited focus on explicit AML enforcement

Goredema (2011: 19) argues that, in some countries, prosecution on specific money laundering charges rarely happen explicitly. Prosecutors tend to focus on predicate crimes, rarely including money laundering charges. Moreover, in many jurisdictions there are still somewhat limited due diligence requirements for financial institutions, leading to infrequent reporting of suspicious activities involving PEPs (Goredema 2011: 19-20; FATF 2008: 5).

Current approaches to institutional strengthening of AML/CFT in fragile states

Against the backdrop of these challenges in developing robust institutional architecture to curb ML/TF, there have been some notable global efforts to assist low-capacity states through technical assistance.

In 2017, the European Commission created the EU Global Facility on AML/CFT to provide technical support to third countries based on the deficiencies identified in their AML/CFT regimes (EU AML/CFT Global Facility n.d.). To date, it has provided demand-driven bilateral technical assistance to 32 countries in the areas of:

- strengthening AML/CFT legislation and regulation, including through the appraisal of the quality of existing frameworks and the integration of emerging policy areas like beneficial ownership into legislation

- building AML/CFT institutional capacity via training of regulatory authorities, financial intelligence units, law enforcement agencies and judicial bodies

- deepening national, regional and international collaboration on curbing illicit finance; the EU GF-AML/CFT works closely with FATF Style Regional Bodies to deliver technical assistance

Thematically, the EU GF-AML/CFT offers support on various topics including training on the verification of ultimate beneficial owners, analysis of SARs and techniques of financial investigation, as well as expertise on sanctions, asset freezing, asset recovery, prosecution of ML/TF offences, antiquity trading and virtual assets (EU AML/CFT Global Facility n.d.).

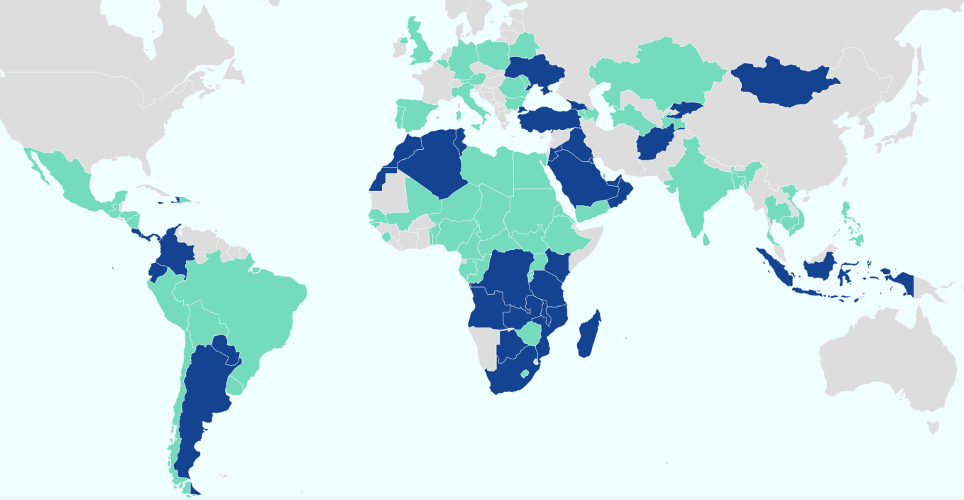

Figure 1: Countries that have engaged with the EU GF on AML/CFT (green in regional activities, blue in bilateral activities)

Another example of an ongoing global assistance programme on AML/CFT is that of the World Customs Organisation (WCO), which carries out a number of enforcement programmes and technical assistance initiatives. Together with the Egmont Group of FIUs and Interpol, the WCO announced Project TENTACLE in 2020. This project seeks to raise awareness of money laundering techniques among customs officials and increase the capacity of customs institutions to tackle them. The main emphasis is reportedly on trade-based money laundering (World Customs Organisation 2020).

The UNODC also hosts the Global Programme against Money Laundering (GPML) to provide demand-driven assistance to UN member states to strengthen their AML/CFT capacity, especially in low-income countries (UNODC 2023). GPML delivers a wide range of activities to improve AML/CFT legal and regulatory frameworks, as well as develop the institutional architecture and practitioner expertise needed to enforce them.

These activities include (UNODC 2023):

- online tools, such as e-learning courses on AML and a professional development system to train financial investigators, coupled with a mentorship programme

- workshops and training courses on topics such as sanctions, financial disruption, cryptocurrency investigation, counter-cash courier techniques, financial investigation, FIU analysis and open-source intelligence

- legal assistance, specifically model laws to guide member states to bring their AML/CFT legislation into compliance with international legal standards and FATF Recommendations

- the establishment of regional inter-agency asset recovery networks

- mentorship schemes, including in-country placements of AML/CFT mentors and prosecutors working on asset confiscation

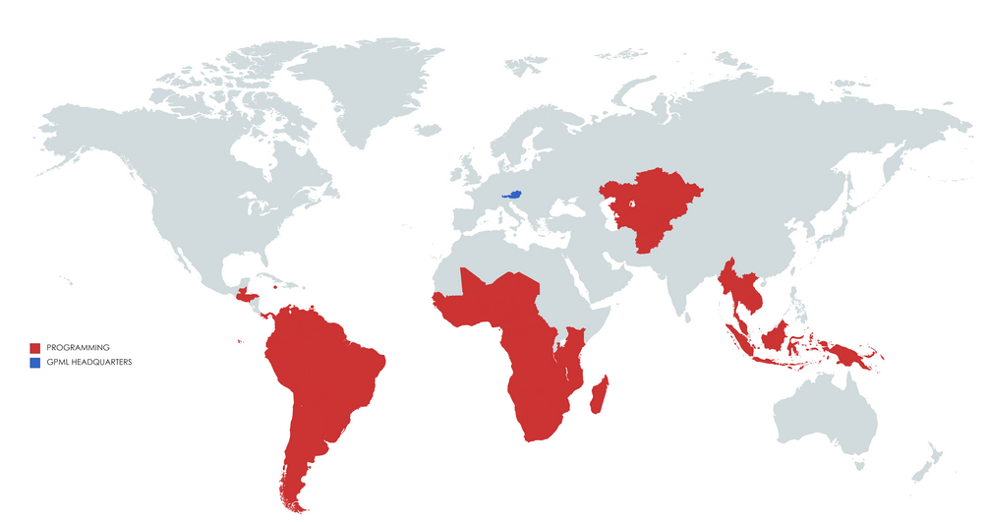

Figure 2: UN member states who have hosted GPML staff and/or benefitted from GPML activities over the last 3 years

Several multilateral financial institutions are also involved in the AML/CFT space. Most notably, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been integrating AML/CFT issues into its core functions (IMF 2023: 5-6). The fund’s approach involves providing technical assistance and capacity building support, with a focus on beneficial ownership transparency, cryptocurrency and the wider fintech industry (IMF 2023: 10).

This builds on the work of the IMF’s AML/CFT Topical Trust Fund, which was launched in 2009 to finance capacity development in AML/CFT (IMF 2009). To be eligible to request support under the trust fund, countries need to be exposed to high risks of ML/TF, be systemically or regionally important to the international financial sector and demonstrate credible commitment from government authorities to improve compliance with AML/CFT standards.

The AML/CFT trust fund has two objectives: protecting the stability of the international financial system and enhancing the integrity of national financial sectors to ease their integration with the global financial system (Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs 2021).

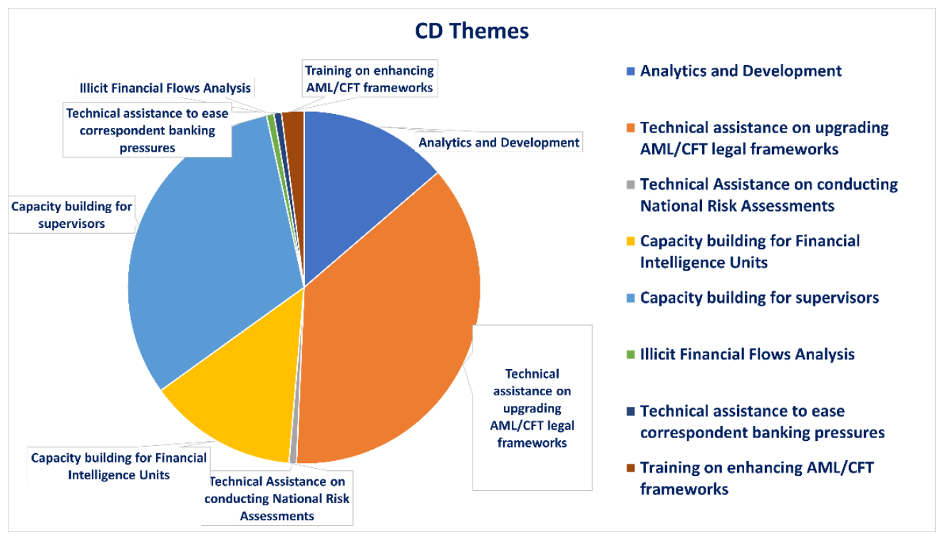

The AML/CFT trust fund is comprised of multiple technical assistance modules, including (IMF 2023: 29):

- identifying AML/CFT areas for reform

- upgrading the legislative and regulatory framework

- conducting risk assessments

- developing national strategies to strengthen AML/CFT frameworks

- building capacity of AML/CFT supervisors of financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs)8a48f11f2264

- improving the structures and tools of financial intelligence units

- AML to tackle proceeds of corruption

- AML to tackle tax crimes

Figure 3: IMF AML/CFT trust fund project modules from 2019-2023 (IMF 2023: 32)

Since 2009, the trust fund has reportedly provided technical assistance to more than 50 countries (Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs 2021). Capacity assistance modalities include research projects, regional workshops and the placement of regional resident advisers, and there are an average 40 AML/CFT bilateral technical assistance projects a year (IMF 2023: 29).

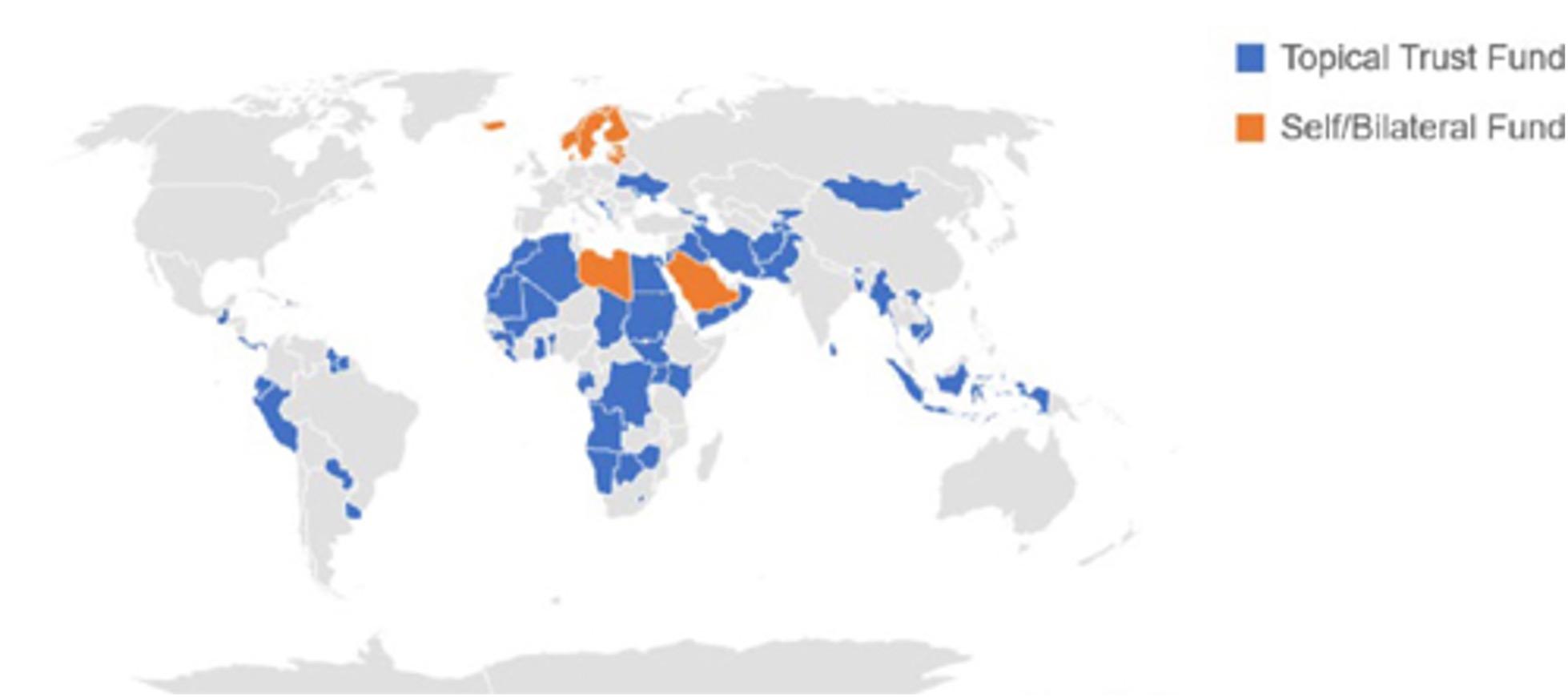

Figure 4 Funding of IMF AML/CFT capacity development activities

More broadly, the IMF conducts several assessments each year of countries’ AML/CFT regimes, (especially where national authorities lack the capacity to do so), reviews FATF reports and participates in standard setting through policy dialogue (IMF 2024).

Finally, the IMF has imposed AML-related conditionalities on states considered by the World Bank to be fragile or conflict-affected, including Cameroon, Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Ukraine, with IMF staff providing capacity building to help these countries implement those conditionalities (IMF 2024: 24, 30).

For its part, the Asia Development Bank (ADB) has carried out technical assistance projects designed to strengthen AML/CFT approaches, methodologies, and controls for non-banking financial service providers. The initiative consisted of training and workshops and several manuals (Asian Development Bank n.d.).

The FATF issued guidance in 2008 on capacity building for “low-capacity countries” to implement FATF Recommendations, which stresses the importance of securing political commitment, conducting diagnostic risk assessments, inter-agency coordination, private sector consultations and engagement with the FATF Style Regional Bodies (FSRBs) (FATF 2008). These themes are explored in more detail in the final section of this Helpdesk Answer.

Technical assistance or capacity development projects on AML/CFT can also be provided by regional cooperative bodies. For instance, the Inter-governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA) is currently implementing a project that aims to enhance AML/CFT regimes through capacity building. GIABA provides assistance through modalities including technical support to national AML/CFT risk assessments, the development of national AML/CFT strategies and capacity building for officials and private entities involved in AML/CFT operations (African Development Bank 2022).

Other international organisations have also provided technical assistance, including the International Development Law Organisation (IDLO), which supported the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) of the Philippines by delivering legal training (IDLO n.d.).

These examples indicate that donor-driven interventions to build AML capacity typically seek to enhance the institutional, legal and operational frameworks of beneficiary countries.

However, donor projects can adopt a variety of modalities beyond “traditional” capacity building interventions such as training, workshops, training of trainers, legal drafting assistance, development of standard operating procedures. Durner and Cotter (2018) list a number of other ways donors can work to strengthen AML institutions in partner countries.

First, donors can provide material support to the relevant bodies. An alternative to providing technical expertise to AML institutions is to co-finance their operations, which can help consolidate their capacity and bolster independence from the executive branch, particularly in contexts where AML institutions struggle to retain or recruit staff (Durner & Cotter 2018: 16).

Another option can be to focus on encouraging inter-agency coordination, especially where diagnostic assessments or FATF MERs have identified this as a constraint. This can be particularly salient when multiple agencies have mandates related to AML/CFT investigations. In such environments, the technical assistance provider can support in bringing key staff together and exchanging information (Durner & Cotter 2018: 17).

Peer institution visits can also be a potentially valuable type of capacity building. The visiting institution’s delegate can gain practical insights into approaches and tools, observe innovative practices and build informal relationships that can underpin future information exchanges, particularly between FIUs. At the same time, Durner and Cotter (2018: 17) argue that peer-learning is most effective between institutions at a similar level of maturity.

More formalised kinds of cooperation, established via a memorandum of understanding or a mutual legal assistance treaty can be good long-term means of strengthening cooperation among institutions. These arrangements can underpin information sharing, cross-border law enforcement collaboration and secondments.

International forums like those facilitated by the Egmont Group and Interpol provide potential platforms for secure information exchange and engagement (Durner & Cotter 2018: 18).

Technical assistance providers can also work through or collaborate with the FATF Style Regional Bodies (FSRBs). Durner & Cotter (2018: 18) argue that building connections between national level AML institutions in these forums can bolster support for and impact of FSRBs.

There are thus several initiatives and approaches to strengthen AML systems in fragile states. The next section attempts to synthesise some of the lessons from the literature.

Lessons learned in strengthening AML/CFT systems in fragile states

Strengthening AML/CFT infrastructure is a gradual process

Institutional capacity building programmes in fragile states can fail where they introduce unrealistic burdens on states (Pritchett et al. 2012: 2). Durner & Cotter (2018: 9) thus argue that institutional development should be gradual and systematic, focussing on delivering small, repeated successes and incrementally scaling up feasible reforms while working with the grain.

AML programmes in fragile settings must adopt a bespoke approach

A clarion call across much of the literature is the importance of conducting robust background analysis of the programming context to ensure the design and implementation of an intervention corresponds to real, underlying needs (Durner & Cotter 2018: 9).

As Scharbatke-Church and Chigas (2016: 16-17) argue, one of most frequent reasons anti-corruption programmes fail in fragile settings is irrelevance, which arises where programme design is not firmly rooted in high quality analysis.

Particularly in states affected by fragility, effective AML/CFT capacity development programmes must be tailored to the specific legal, economic and cultural contexts of the countries they aim to assist, including the nature of its money laundering and terrorist financing risks. Cohen (2018), for example, calls for donor ex-ante assessments to “incorporate analyses of financial flows and the illicit economic interests of elites into their analysis”. Sources of information to assist the diagnosis of institutional strength could include the FATF MER reports, key informant interviews, reports by regional bodies and multilateral development banks, as well as leaks and open-source intelligence (Durner & Cotter 2018: 9).

Consultations should involve a wide array of stakeholders at both senior and junior level, including from FIUs, regulators, law enforcement and judicial actors (Durner & Cotter 2018: 10), as well as representatives from the broader private sector, civil society and academia (Passas 2015: 11).

Anchor local ownership

Once the context and local political economy has been analysed, Durner & Cotter (2018: 12) argue that the inception phase of an AML/CFT programme should focus on building strong relationships with the project target group. This requires candid and open dialogue that encourages local ownership and ensures that project activities align with local capacities, needs and perspectives.

This is easier said than done. AML/CFT programmes often touch on sensitive topics that relate to national security or are heavily politicised, such as intelligence capabilities, information security and corruption. These challenges can make it difficult to get the right level of access to establish a baseline and an adequate needs analysis (Durner & Cotter 2018: 12).

One thing that could help in this process are measures to secure high-level support for the intervention objectives, such as formal political endorsement and clearance from all relevant senior-ranking officials. If this is not forthcoming, it should inform the decision whether and how to proceed with the intervention.

Another way to anchor local ownership in AML/CFT capacity development projects can be to involve local experts wherever possible. Local staff in project manager or senior adviser roles bring detailed knowledge of the local context, as well as a network that can help during the roll out of the intervention (Durner & Cotter 2018: 19). Investment could also be made into building local expertise and skills, which the UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa (2022: 18) and the FACTI Panel (2021: 33) have identified as an area in need of improvement in the field of money laundering in low-income countries.

Finally, donor countries could consider supporting efforts to increase the representation of fragile states in relevant standard-setting forums and decision-making processes, notably FATF, which may strengthen the local ownership of global AML/CFT measures (Maslen 2023: 13).

Inter-agency coordination

The effectiveness of AML/CFT measures is highly contingent upon the level of coordination between the various agencies that play a role in establishing and enforcing an AML/CFT regime (Passas 2015: 11). Without well-defined roles and responsibilities, AML/CFT efforts can become fragmented, leading to inefficiencies and gaps in enforcement (Goredema 2011: 10; Chêne 2017: 4).

For instance, FIUs may receive and analyse suspicious transaction reports, but actual enforcement of laws might depend on other institutions such as law enforcement bodies, prosecutors, customs or anti-corruption agencies (Goredema 2011: 20). Lack of coordination can also hinder investigative capacity if no single agency has all the information needed, making information sharing at the operational level critical (Durner & Cotter 2018: 17).

Donor-oriented programmes could potentially focus on the coordination challenge between constituent parts of the institutional architecture. In such environments, the technical assistance provider can encourage key staff to exchange information and provide a forum for them to do so (Durner & Cotter 2018: 17).

Effective AML requires public-private collaboration

Another lesson from past experiences with AML/CFT related institutional strengthening is the importance of establishing collaborative relationships with stakeholders most affected by AML/CFT laws and procedures. Strong AML-CFT regimes require partnerships between committed public and private sector actors, whose incentives are generally aligned (FATF 2008: 8).

In fact, it may be counterproductive to impose stringent compliance standards without ensuring some buy-in from those who ultimately must comply with the rules. Lessons learned from efforts to curb ML and TF risks in remittances indicate that the costs of compliance can end up pushing legal intermediaries out of the formal sector entirely, potentially leading to higher ML risks (Passas 2015: 2).

Lack of capacity is not just a challenge for the public sector. Financial institutions are not always in a position to implement very stringent due diligence, KYC, reporting and other compliance regulations, due to a lack of data or even lack of skilled compliance personnel. Furthermore, the lack of official, reliable information can make it difficult for financial intermediaries to decide whether a client's financial activities are illicit in origin (Goredema 2011: 9). Depending on where the ex-ante assessment has indicated the most severe capacity deficits, providers of technical assistance could choose to provide training to private sector obliged entities such as financial institutions, banks, real estate agencies and asset management services.

Donors could also seek to nurture collaborations between private and public sector institutions to facilitate better information sharing, improve financial crime investigations, and enhance the quality of SARs and STRs (AML Compliance blog 2022).

In several high-income countries there are indications that formalised public-private partnerships in the domain of AML/CFT have led to improvements. In the United States, the FinCEN Exchange allows financial institutions to engage in (voluntary) information sharing with law enforcement, national security agencies, financial institutions and FinCEN (AML Compliance blog 2022). Such partnerships could lead to a more coordinated and efficient AML regime, while reducing “unnecessary and whole-sale de-risking”, according to the Wolfsberg Groupa881674d4d2b (AML Intelligence 2022). However, the viability of such models in fragile settings with poorly regulated financial sectors is likely to depend to an even greater extent on the maturity and commitment of commercial entities.

In the wider anti-corruption field, several initiatives have applied collective action models in different sectors in fragile states. Examples include the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative; CoST - the Infrastructure Transparency Initiative; the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network and Open Ownership. Some of these initiatives are primarily driven by the private sector, others by governments, but they are united in that they seek to establish platforms for coordination against corrupt or illicit practices.

In his examination of experiences from Afghanistan, Somalia and India, Passas (2015) argues that developing effective AML strategies requires engagement with informal financial intermediaries. He contends that informal hawala networks can contribute positively to efforts aimed at curbing money laundering and terrorism financing, provided they are engaged appropriately. He points to cases where hawaladars (operators within hawala networks) have assisted with both the uncovering of terrorist and drug trafficking operations as well as with evidence in prosecutions. Despite challenges, informal remittance channels in cash-based, low-income societies may offer channels for positive change that can contribute to enhancing financial regulation and oversight in these high-risk environments (Passas 2015: 2). In this view, working with actual, on-the-ground systems could help make AML/CFT oriented programming more context sensitive and credible.

Reinforce the operational independence of financial intelligence units

The institutional design of financial intelligence units (FIUs), including their placement within the government apparatus, significantly influences their performance. The most common model of an FIU, the administrative model, is typically set up within another government body such as a finance ministry, a central bank or another central regulatory body (Marcus 2019: 4). Administrative FIUs can serve as intermediaries between financial institutions (and other obliged entities) and law enforcement, which can potentially lead to better coordination. However, administrative FIUs may be subject to political interference and often have limited legal powers to gather and analyse intelligence (Marcus 2019: 4).

FIUs can also be placed within law enforcement agencies, in which case they can benefit from wider investigative powers and better enforcement capabilities (Marcus 2019: 5). However, this type of FIU may place less emphasis on AML/CFT preventive measures, and there is a risk that obliged entities and financial institutions will be more reluctant in sharing detailed information than if the FIU operates at an arms-length from law enforcement (Marcus 2019: 5).

Less common are FIUs which operate as part of the judicial branch. However, this institutional setup can allow the FIU to benefit from greater freedom from political interference and the ability to leverage judicial powers like asset freezing. This can potentially be quite effective in jurisdictions where the law enables high levels of banking secrecy (Marcus 2019: 5).

Ultimately, the choice of FIU model depends on a country's legal system, criminal justice policies, resources, and the expected volume of reports (Marcus 2019: 5). What matters most is ensuring the operational independence of FIUs (Marcus 2019: 1), which providers of technical assistance could attempt to safeguard.

This autonomy could be enhanced through technical assistance to human resources management alongside financial support to ensure that FIUs enjoy adequate expertise and resourcing, such that they are not overly dependent on the whims of incumbent officials in the executive branch (Marcus 2019: 6-7).

AML/CFT programming must be sensitive to Do No Harm principles and avoid financial exclusion

While there is broad consensus of the necessity of a global anti-money laundering regime, there are some concerns about the unintended ramifications of these systems in fragile states, particularly in terms of AML/CFT slowing the delivery of humanitarian assistance (The New Humanitarian 2023), in pressuring civic space (France 2021) and in exacerbating financial exclusion (Center for Global Development 2015).

Indeed, the implementation of AML/CFT regulations have sometimes led banks to adopt a practice known as “de-risking” to limit their exposure to illicit finance in certain low-income or fragile countries. Knoote and Malmberg (2021: 18) highlight how excessive de-risking initiatives, while intended to avoid risks of involvement in financial crimes, often result in financial exclusion of citizens and their associations in affected countries.

Ironically, in the literature on AML/CFT in fragile states, financial exclusion itself is often highlighted as a risk factor in money laundering, terrorist financing and other forms of illicit finance (Passas 2015). An OECD report focussing on illicit trade in West Africa found that financial exclusion contributes significantly to the growth of criminal markets and illicit financial flows, particularly in countries where reliance on cash transactions and alternative remittance systems like hawala networks are prevalent due to limited access to formal banking (OECD 2018b: 108). The OECD (2018b: 108) suggests that better access to official credit for artisanal gold miners in Mali may have helped to progressively formalise the sector, by giving them access to the capital needed to afford licences and buy equipment.

The unintended consequences of poorly designed AML/CFT systems can also affect civil society organisations – including those that work to curb corruption, organised crime and dirty money – by restricting access to funding and limiting their operational freedom (France 2021; Knoote Malmberg 2021: 17-18).

International partnerships, regional work and global cooperation

Another recurring theme in the literature is the potential of regional and global cooperation to strengthen efforts against money laundering. For instance, in its recent report on IFFs in Africa, one of UNCTAD’s (2020) core recommendations was to strengthen African collective efforts to counter corruption and money laundering on the continent. Supporting and further developing regional bodies, such as the Inter-governmental Action Group against Money-Laundering in West Africa, is one pathway (UNCTAD 2020). Another example relates to the Central African Economic and Monetary Community, which in 2016 adopted AML/CFT regulations that its member countries are expected to comply with (Lando 2022: 97).

Cross-border collaboration can help countries to overcome challenges like legal and regulatory disparities, data sharing and trust issues, and encourage authorities in different jurisdictions to share information such as bank account details, property holdings, and trade patterns and volumes (Sanctions Scanner n.d.).

The need to coordinate AML/CFT efforts applies not only to aid-recipient countries. The establishment of multi-donor coordination platforms that regularly seek to align objectives between providers of technical assistance and identify areas of competitive advantage and cooperation could help avoid issues of duplication between international organisations and donors (Durner & Cotter 2018: 19). Referring specifically to fragile and post-conflict states, Cohen (2018) calls for international actors, including UN agencies and financial regulators, to set up “lines of communication” to share “observations on the ground and information on suspicious transactions in places like London, New York, Paris, Geneva and Dubai”.

Policy coherence with other development strategies

There is also some scepticism about the efficacy of conventional law enforcement approaches in curbing illicit financial flows and money laundering in fragile settings in which criminal economies “provide basic livelihoods” (OECD 2018b: 108). One implication of this for those looking to strengthen AML systems in fragile settings could be to focus on reforms to ensure that the basic functions of the criminal justice system are operational. In environments in which the wider justice system is highly dysfunctional, efforts to establish highly specialised AML institutions may struggle to make much of an impact, even if they do develop into “pockets of effectiveness”.

Tackling potentially sophisticated forms of financial crime relies on considerable state capacity, resourcing and political backing. Precisely these conditions are likely to be lacking in fragile settings, which may suggest that more fundamental state-building measures should be prioritised. The OECD (2018b: 111), for example, recommends that donors wanting to support aid-recipient governments to crack down on illicit economies align law enforcement, criminal justice and security sector responses with interventions intended to promote “sustainable livelihoods, financial inclusion and strategies to ensure integrity in the public services”.

- The UN Statistical Commission defines IFFs as “financial flows that are illicit in origin, transfer or use, that reflect an exchange of value and that cross country borders” (UNCTAD 2023: 5).

- Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions encompass entities that are not primarily involved in financial activities but handle assets that could potentially be used to launder money or finance terrorism. They include casinos, real estate agents, lawyers, accountants, company service providers and dealers in precious minerals.

- The Wolfsberg Group was the first business-driven collective action compact, bringing together some of the world’s major financial institutions to work collectively for better AML/CFT compliance (see Pieth 2012: 9).