Over 1 billion US$ in hidden debt

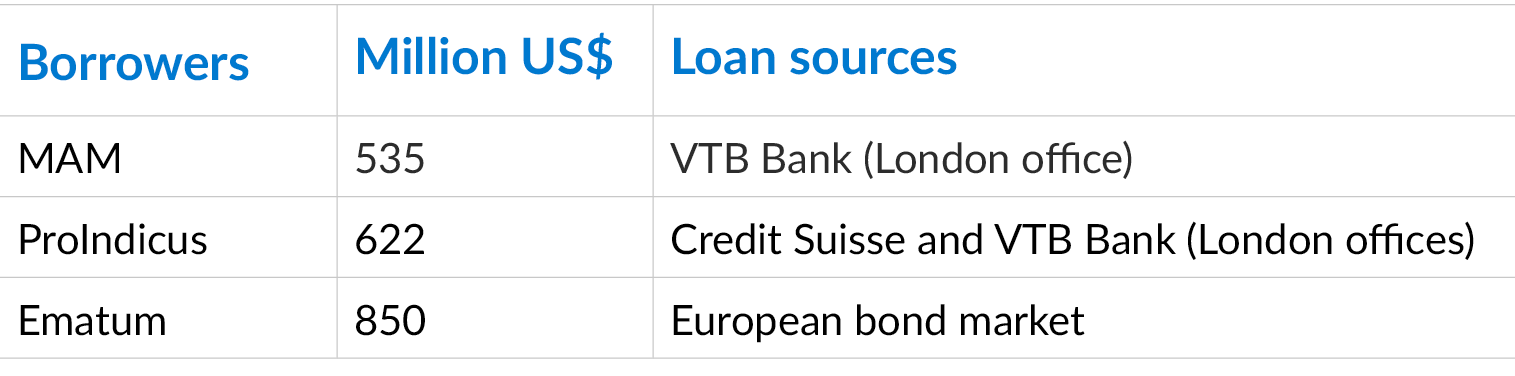

It was revealed in 2016 that semi-public entities in Mozambique had taken on debts backed by government guarantees without submitting them to the Assembly of the Republic as the Mozambican constitution requires (Williams and Isaksen 2016). The state-backed debts were taken on by three companies – Mozambique Asset Management (MAM), ProIndicus, and Empresa Moçambicana de Atum (Ematum):

Outwardly, it appeared as if the loans should pay for establishing tuna fishing and maritime security businesses. The loan sources were the London offices of Credit Suisse and VTB Bank for ProIndicus, VTB Bank for MAM, and the European bond market for Ematum. In spring 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) confirmed the debt to be over US$ 1 billion and announced the suspension of its programme with Mozambique. Suspecting some form of corruption, the G14 group of donors to Mozambique suspended all general budget support in May 2016 (Williams and Isaksen 2016). The IMF now categorises the country as being in public debt distress.

A thorough analysis of this case illustrating how illicit financial flows not only leave developing countries but can flow back into them, bypassing formal oversight mechanisms and lending rules is available in a 2016 U4 Issue: Corruption and state-backed debts in Mozambique: What can external actors do?

Audit into the hidden loans case – main lessons

The full report of an audit into the Mozambique hidden loans case was leaked in August 2017. The Mozambican attorney general’s office (PGR) commissioned the report from the forensic audit firm Kroll. Sweden and the IMF financed the work. The PGR originally promised to publish the full audit report, but have not yet done so.

The following analysis draws on the Kroll audit report and publicly available analysis of its results. We have also interviewed three individuals who know the loans case and audit process intimately – and refer to them as interviewees A, B, and C.

Secrecy persists and cooperation was limited

Kroll’s requests for detailed information about the loans from ProIndicus, Ematum, and MAM resulted in only very limited information shared. Trial balances and bank statements were incomplete and documentation around loan facility agreements and supplier contracts patchy (Kroll 2017). Hanlon (2017b) illustrates the degree of secrecy by pointing to a claim that Ematum kept 788 kg of intellectual property and technology transfer documents away from the auditor.

Interviewee C suggested that although development partners in Maputo are concerned about this secrecy – some believe that the national security concerns cited as reasons for holding back information are plausible.

Interviewee B indicated that an important question for development partners is whether the CEO of the three companies acted alone or with higher-level consent in obtaining the loans and maintaining secrecy around them. This CEO has self-identified as a senior official of the Mozambican security services (SISE)– Antonio Carlos do Rosario. Based on the available information, criminality, corruption and a certain vision of Mozambican patriotism, or some combination of these, are all plausible motives for the practices uncovered by the audit.

Business plans for the three companies were not credible

Kroll analysed the business plans and available feasibility studies. According to these, the three companies would generate combined operating revenues of US$ 2.3 billion by December 2016 (Hanlon 2017a). The audit found instead that ‘negligible revenue’ had been generated (Kroll 2017), and that there were significant risks that the Mozambique projects would not become operational. Kroll made requests for evidence of comprehensive due diligence undertaken to assess the suitability of specific contractors involved1f48797a0621, but did not receive any (Hanlon 2017a). Reid (2018) suggests Credit Suisse and VTB Bank showed little interest in evaluating the risks to the proposed business plans.

Interviewee A noted that there may have been an element of commission-hunting on the part of the banks. At the same time, one theory to explain the lack of credible business plans is that the loans would pay for arms and security equipment. The loans themselves appeared in 2013/2014 – coinciding with an April 2013-resurfacing of the conflict with the Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo). The self-identification of Antonio Carlos do Rosario adds plausibility to this theory (Hanlon 2017a).

Misconduct and rule breaking likely on many sides

Information in the Kroll report indicates likely misconduct and rule breaking on many sides. Although it does not make any formal allegations, Kroll suggests that Credit Suisse, as well as the three companies and their CEO, may have committed criminal acts (Kroll 2017, Hanlon 2017b). And although the Kroll audit could not offer insights regarding the due diligence undertaken by Credit Suisse or VTB Bank, the Ematum business plans and feasibility studies it reviewed included no plans for onshore tuna storage and processing, no people supplied for training, and no means of linking-up to the ProIndicus radar system.

The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) have opened probes into the roles of Credit Suisse and VTB Bank in the loans (Wirz et al 2017, Jubilee Debt Campaign 2018). In terms of the potential for involvement of past and current members of the Mozambican government’s executive branch, Interviewee A noted that SISE is a semi-autonomous body linked to the presidency and the current president served as defence minister when the loans were taken out. One theory is that the current president may have supported the audit because such an investigation would have no way of finding its way back to him, although there is too little data at this point to support such interpretations. A possibly related observation is that the decision to accept the audit came during a rapidly accelerating economic crisis precipitated by the hidden loans case.

Prospects for justice and accountability

Justice and accountability outside Mozambique

Criminal or other legal proceedings with regard to the involvement of the London-based banks are a possibility, with ongoing investigations by the FCA and FBI (Wirz et al 2017, Jubilee Debt Campaign 2018). The allegation is that the London-based banks may have violated UK anti-money laundering legislation by not providing the extra scrutiny needed in cases where the beneficial owners of companies receiving loans are politically exposed persons (FI News 2017). The Swiss financial regulator also reportedly opened a probe into the involvement of Credit Suisse, but has deferred to the UK and US investigations (Ward 2017).

In addition to the potential for criminal or other legal proceedings against the banks in the UK and the US, there is a legal reform possibility in the UK that could prevent other cases like the Mozambique situation. In July 2017, Roger Godsiff – a British Member of Parliament (MP) – submitted a motion to debate transparency of developing country debts, based on a concern about the Mozambican loans case:

‘(it) calls for measures to ensure that all loans under UK law given to governments or with government guarantees are disclosed publicly at the time they are made and comply with the law of the country concerned.’

Godsiff’s motion was signed by 100 MPs. But given no member of the majority British political party in government (the Conservatives) signed the motion it is unclear whether such reforms will be forthcoming.

In terms of aid conditionality, bilateral and multilateral donors to Mozambique have mostly not resumed support to the government. All 14 donors who used to provide general budget support have suspended their funding (Club of Mozambique 2018). DFID, for example, notes that all UK funding to the government was suspended when the loans case was uncovered in 2016, and that the case for resumption will be reviewed against evidence of ‘government reforms and good value for money’ (PDF).

A 2018 IMF staff report notes that although the Mozambican government announced a debt restructuring in October 2016, there had been a ‘lack of significant progress.’ As stated in the same report, the Mozambican authorities noted that they would actively resume discussions for restructuring their external public debt with six official creditors (Libya, Iraq, Angola, Bulgaria, Poland, and Brazil). A first meeting of foreign creditors would take place in London in March 2018.

Aid or lending suspensions cannot, however, be viewed as equivalent to justice since it is unlikely that such measures will directly affect individuals responsible for wrongdoing in the loans case.

Justice and accountability within Mozambique

In January 2018, the Mozambican attorney general’s office (PGR) opened a case at an administrative tribunal to establish ‘financial responsibility’ for the loans (Cotterrill 2018). Interviewee C notes that the Attorney General Beatriz Buchili appears to have the support of the president in pursuing this case, and that support from Western development partners is crucial given the powerful actors apparently implicated. The March 2018 IMF country report on Mozambique (PDF) describes this case – presumably erroneously – as a ‘criminal investigation.’ It notes that judicial proceedings have been delayed due to the complexity of the mutual legal assistance process, which requires assistance from the UK, the US and the United Arab Emirates.

Talking with journalists in May 2018, a spokesperson for the tribunal stated it was undertaking technical work to investigate the loans and guarantees (Club of Mozambique 2018). Long-term observers remark that the tribunal is unlikely to lead to criminal charges, however. Joseph Hanlon – an expert on Mozambique and international aid and development – has stated that the charges ‘look like a slap on the wrist for a few scapegoats’ (Cotterrill 2018).

Interviewee B suggested that, in addition to administrative legal proceedings brought by the attorney general, civil action cases might be pursued by ordinary Mozambicans (i.e. the victims) against the Mozambican state. However, no such case had been opened at the time of writing this Brief. Another possibility invoked by Interviewee B was the establishment of a specialised court with support from Western development partners.

Whatever form legal proceedings in Mozambique take, Interviewee C noted that the CEO of the three companies has threatened to fight any attempt to hold him accountable. Given his position as a high-ranking officer of SISE, this can be interpreted as a threat of violence.

Anti-corruption follow-up actions development partners to Mozambique should take

In the event that legal proceedings in Mozambique fail to deliver accountability for the hidden loans case donor countries could, in theory, apply two basic external sanctions:0cfdd4136ef8

- Not resume financial support to the Mozambican government

- Apply regulatory restrictions on foreign firms operating in Mozambique that are headquartered in donor country jurisdictions

Neither option is straightforward. Although there is little appetite among development partners to resume the same forms of support previously available to the Mozambican government, not resuming support to the government at all could further destabilise an already fragile political situation. This is particularly the case in the North close to the natural gas projects. It will also hurt Mozambique’s poor who would suffer under reduced social services unless perhaps alternative non-governmental programmes were available.

Applying serious regulatory restrictions on foreign firms operating in Mozambique could be detrimental to Western countries’ own economic interests.fcc7689198ab It may lead to further political destabilisation, and hamper the government’s efforts to regain debt sustainability. At least in terms of sanctions, donors’ potential anti-corruption actions therefore appear straightjacketed. Yet, development partners hold some cards they should play:

Facilitate information exchange with the UK and US investigations and take follow-up actions in Mozambique

To the extent possible – given the rules under which the FCA (UK) and FBI (USA) operate – development partners in Mozambique should closely follow their investigations and exchange information with them. Applying sanctions with regard to the London-based banks via these investigations could increase the likelihood of sanctions against individuals in Mozambique. This will however depend on the breadth of the respective investigations, their specific mandates, the data they uncover, and the legal limits in the various jurisdictions involved as to the use of this information. Travel and visa bans on individual Mozambicans found to have been involved in wrongdoing is one set of non-aid measures development partner governments could pursue following formal investigations. Practical experience from the application of travel and visa bans by the UK and US governments on corrupt individuals in Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is available to help guide such actions.

Support the attorney general’s efforts, consider a specialised anti-corruption court and victims’ civil lawsuits

Obtaining justice and accountability for wrongdoing in the loans case within Mozambique will be an arduous task. The existing administrative tribunal will need strong, consistent support from development partners for any progress to occur. Such support may be mutual legal assistance, legal or other analysis, cross-border network building, peer-to-peer coaching (e.g. via Norad’s Corruption Hunter Network), and meeting facilitation.

At the same time, there is a high risk that the tribunal will not succeed in holding actual wrongdoers to account. It is therefore advisable for development partners to explore other options, including support to establish a specialised anti-corruption court. In many countries, frustration with the justice machinery’s inability to deal with corruption cases has led many countries to set up such specialist courts. Stephenson and Schuette (2016) mapped this type of court in 17 countries. They note ‘the need for greater efficiency in resolving corruption cases promptly and the associated need to signal to various domestic and international audiences that the country takes the fight against corruption seriously’ as the most common argument to set up these courts. Although there are no definitive best practices for such courts, the mapping presents existing models and experiences that may guide those who consider similar institutions.

A further option for development partners would be to encourage legal support via third parties to Mozambican citizens who wish to bring civil action cases against the Mozambican state in relation to this case.

Follow-up the IMF’s monitoring systems for protecting countries against unsustainable debt

All interviewees agreed that the IMF could and should have done more to protect ordinary Mozambicans against the Mozambican state guaranteeing private loans that ultimately led to unsustainable levels of public debt. The primary control mechanisms to protect against such loans should have been those embedded in Mozambique’s constitution and legal system, as well as in the country of the lending banks – the UK. Even so, interviewees noted that the IMF could have more actively monitored public and private loans that could affect the country’s overall debt sustainability. Development partners should therefore instigate a review of the IMF’s monitoring systems for protecting countries against unsustainable levels of public debt. This should include considering whether a more active, preventative, monitoring system might have anti-corruption benefits by providing a “failsafe mechanism” in cases where wrongdoers seek to “game” national controls.

- These contractors were Privinvest Shipbuilding and Abu Dhabi Mar.

- Given that the opposition parties Renamo and the Democratic Movement of Mozambique (MDM) are critical of the hidden loans case, Mozambican voters could, in theory, also sanction Frelimo via the October 2019 presidential, legislative and provincial elections.

- Anadarko (USA), Exxon (USA), and ENI (Italy) are the main investors in Mozambique’s natural gas sector.