The renewable energy sector has great potential to create positive environmental and economic change across Zambia. Historically, however, the energy sector has been both a source and a target of corruption as it has the potential to generate massive economic rents.46adadcea5bf Moreover, the advent of independent power producers (IPP) has promoted the possibility of collusion between public officials and firms bidding for licenses. Where this occurs, it may lead to the overlooking of viable bids, causing a significant increase in costs. GAN Integrityd1f2a39fc455 reports that there is a moderate to high risk of corruption in the public utilities sector in Zambia, a finding that is confirmed by the perception index of Transparency International (TIZ). Particular to the energy sector, Mkokweza7c1460bb7018 finds that the Energy Regulation Act No. 12 of 2019 increased the powers of the Minister of Energy, which in turn has enhanced the potential for corruption. This is because the new law allows the Minister to overturn various institutional decisions at his or her discretion. The law was intended to attract vertical private participation in the energy sector and stimulate off-grid generation. However, by over-empowering the minister and allowing unchecked discretion, the law undermines the basic principles of transparency and accountability. Interviews conducted in the sector by the authors in June and July of 2021 confirm that corruption is a great concern, impacting on private sector investment and expansion.

At the request of U4 and Sida, this discussion paper provides a background and analysis of the continuous corruption in the renewable energy sector, looking at the following questions:

- With the restricted space and capacity of civil society, combined with a narrow and elite-dominated political space that is available in Zambia, what kinds of anti-corruption interventions are likely to have an impact?

- Furthermore, what evidence do we have about the effectiveness of anti-corruption interventions in Zambia over the last two decades that we can learn from?

To answer these questions above, the authors opted to embed the legal analysis in the political context of Zambia. A critical political economy approach ensures that external factors, notably the power structures and elite pacts, are taken into account. Zambia’s regime type ultimately shapes the operational setting of corruption and determines the success of anti-corruption initiatives.

Taking this approach enables us address the following overarching question:

Given Zambia’s political economy and legal framework, what are the existing mechanisms for redressing corruption that can be deployed in Zambia’s renewable energy sector?

In order to understand the political salience of corruption, the authors start their analysis with the President Mwanawasa era (2001–2008), which saw establishment of numerous anti-corruption initiatives and was followed by a period of decline in corruption. The case study in this article serves to highlight a legal mechanism as a successful way to fight corruption in the energy sector. The research methodology consists of a multi-disciplinary literature review and is combined with semi-structured interviews. The twelve interviewees represent the various stakeholders of the renewable energy sector in Zambia, namely the private sector, the financial institutions, the donors, the regulatory authorities and civil society.c98f74e962e4

The paper is structured as follows. First, we provide background information on Zambia’s political economy which situates the study; second, we provide a review of anti-corruption measures in Zambia and their effectiveness. This is followed in the section on potential anti-corruption interventions for Zambia’s energy sector, by a case study on debarment in the energy sector. Fourth, we consider how corruption impacts Zambia’s renewable energy’s private sector. Lastly, we look at potential anti-corruption interventions from comparable contexts and Zambia itself before we conclude and point to possible ways forward. It is important to note that the article was written ahead of the 12 August 2021 elections, which saw a change of regime in Zambia. The transfer of power has the potential to have a significant impact on the anti-corruption environment and will be taken into account in the final section.

Zambia’s political economy

‘Not very sure of factors that can reduce corruption in the sector. To me the problem is at the top. It starts with top leadership. It is at the highest level, it’s a governance issue.’cdc67e7c5e0c

The political transition in Zambia from one-party state to multi-party democracy in 1991 was accompanied by an ideological shift from state- to market-led economics. This shift required a restructuring and repositioning of Zambia’s economic governance and the civil service more broadly. While the liberalisation opened new avenues for private investors, the political elite had to re-establish itself in the new political and economic settlement. The reintroduction of multi-party rule in 1991 saw Zambia shift from a broad-concentrated to a broad-dispersed form of political settlement.89b897cdec22 Zambia has seen three electoral turnovers, that is, from the United National Independence Party (UNIP) to Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), MMD to Patriotic Front (PF), and PF to United Party for National Development (UPND). Zambia has also experienced coalitional shifts within the parties themselves, especially following the deaths of presidents Mwanawasa (2008) and Sata (2014). Below we highlight the main changes that provide an important backdrop to our discussion on governance and corruption in Zambia.

- Economic liberalisation led to ruptures between those in power and major socio-economic interest groups, like the trade unions and other professional associations. Over time, countervailing powers over the presidency have weakened.

- The privatisation of state-owned companies like the mines – the traditional mode of patronage – made State House, political parties and political actors more susceptible to the interests of politico-economic entrepreneurs (the so-called tenderpreneurs).f15d977efcf8

- Privatisation and the quest for short term ‘political survival’ had a profound effect on public finances as alternative rents were sought elsewhere within government entities, notably through government contracts, procurement, the national electricity company, pension funds, etc. In the process, privatisation undermined the relatively formal structures that previously guided accountability and oversight of the business lobby and associated deal-making processes.

- Particular to the PF regime (2011–to date) is a renewed centralisation of power and the supremacy of the Party reminiscent of Zambia’s one-party state (1972–1990). When PF came to power in 2011, it gradually implemented its manifesto, which set out that, ultimately, it is the party that controls the running of the government. The politicisation of the civil service has had an impact on the efforts to curb corruption, as informal rules became more dominant.

- The rapid turnover of presidents, parties and factions since 1991 had a negative effect on the bureaucracy, as turnovers in personnel were constant, ranging from State House staff all the way down to the level of Directors of Departments in Ministries and embassy staff. Ministries were variously added, removed and renamed and the boards of regulatory bodies overhauled by every new government (2011, 2015, 2016). Appointments were based on party political affiliation and being representative of a particular social identity rather than necessarily on competence.

That said, corruption has not always been a salient feature of Zambian society. Under the leadership of President Mwanawasa (2001–2008) corruption was more contained. The circumstances under which this occurred will be detailed below as they provide important lessons for possible solutions.

What can be ascertained is that Zambia has seen a rapid growth of corruption since 2015. Whereas in an earlier desk review by U4, published in 2014, there was a sense of optimism about the measures taken against corruption:

Zambia has made considerable progress in the fight against corruption in the last decade, as reflected by major improvements recorded in main governance indicators. The legal and institutional frameworks against corruption have been strengthened, and efforts have been made to reduce red tape and streamline bureaucratic procedures, as well as to investigate and prosecute corruption cases, including those involving high-ranking officials. In spite of progress made, corruption remains a serious issue in Zambia, affecting the lives of ordinary citizens and their access to public services.bb256f910634

By contrast, an updated U4 desk review in 2020, noted the following:

Zambia faces significant corruption challenges; public procurement and the justice sector are especially affected. A progressively authoritarian regime has resulted in increasing political violence against the opposition and government critics. With the onset of COVID-19, there are fears that, in a bid for survival, the ruling party may find ways of personal enrichment at the expense of public welfare.

This latter desk review further noted that the Zambian market functions under a weak institutional framework in which corruption and red tape play a major role.5da31bf18bdf In 2019 Zambia ranked 113 out of 180 in Transparency International’s 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) with a score of 34/100.

Potential anti-corruption interventions for Zambia’s energy sector

Given Zambia’s political economy and legal framework, what are the existing mechanisms for redressing corruption that can be deployed in Zambia’s renewable energy sector? The section discusses the background to the legal framework, gives an overview of the legal framework and then provides an overview of existing interventions or mechanisms for redressing corruption.

Background

At independence in 1964, Zambia did not have its own autochthonous legislation dedicated to fighting corruption. It instead relied on laws that were inherited from the United Kingdom.8edc877656ab The inherited laws included the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1916, the Public Bodies Corrupt Practices Act of 1889, and the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1906. The Penal Code, which codifies many conventional crimes, was for many years the principal legislation governing criminalisation of corruption in Zambia. Its main focus was on financial misconduct in the public sphere.

It was not until 1973 that the Zambian government began to respond to corruption at a policy level with the adoption of the Leadership Code. The code governed government officials and made it illegal for leaders to own a business or earn additional income other than their salaries. In terms of scope, the code applied to all persons holding positions in the ruling party (United National Independence Party), the civil service, local authorities, state enterprises, institutions of higher learning and in government.48ad6aa98038 It has to be noted that enforcement of the leadership code was inconsistent. It was also unpopular because of its restrictions and was abolished in 2002.

Another major development in the fight against corruption was in 1971, when government established the Special Investigations Team on Economy and Trade (SITET) with the purpose of investigating economic crimes. This was at the time when Zambia had in place strict exchange control regulations that prohibited the holding and externalisation of foreign exchange without the written permission of the central bank.f84f40ea1c9a Its mandate extended to matters of money laundering, illegal foreign exchange dealings, hoarding of commodities and smuggling. Although SITET was relatively successful in accomplishing its tasks, it was abolished in 1992 as it was seen to be inconsistent with democratic standards.dab98899214d

It was in 1980 that Zambia finally passed a specific law dealing with corruption: the Corrupt Practices Act of 1980. The act pooled or consolidated into one piece of legislation all crime-related offences and criminalised corruption both in the private and public sectors. To deal with corruption, it set up a specialised body, the Anti-Corruption Commission, to be the principal law enforcement wing fighting corruption. The Corrupt Practices Act has undergone several reforms, but its substance and spirit has been preserved in its successor legislation, currently reflected in the Ant-Corruption Act of 2012.

Current Anti-Corruption Framework

Zambia has a fairly comprehensive legal framework for addressing corruption. Although the law is not specific to the energy sector, it is of general application and deals with corruption across all sectors. The main pieces of legislation include the following:

Anti-Corruption Act 2012

The Act provides for the continued existence of the Anti-Corruption Commission as the main body responsible for fighting corruption in the country.4a67da21d864 The Commission is established as an autonomous institution not subject to the direction or control of any person or authority.347b4442092e The functions of the commission include preventing, investigating and prosecuting crimes of corruption.

Significantly, the Act contains a list of offences amounting or relating to corruption. It includes proscribed conduct in both the private and public sectors. The list of offences includes abuse of authority, possession of unexplained property, conflict of interest, payment of bribes, and concealment of property.671ec30f8590

The Forfeiture of Proceeds of Crime Act 2010

The Act provides for forfeiture to the state of any property believed to be derived from commission of a crime. The underlying idea is that those who commit crimes should not benefit from them, but should be deprived of the property accumulated from the crime. Forfeiture is generally done in one of two ways: conviction-based (where a person is convicted of a criminal offence) and civil forfeiture (where authorities simply target the property but the concerned person may not be visited with criminal prosecution).

The Public Interest Disclosure (Protection of Whistleblowers) Act 2010

The Act provides a framework for the protection of whistleblowers or those who disclose information, exposing corruption, crimes, maladministration or other similar wrongs. It sets out mechanisms for ensuring that the whistleblowers are protected from reprisals as a result of their actions.

The Plea Negotiations and Agreements Act 2010

This law sets out the mechanism for plea agreements. It only recognizes one type of plea agreement, that is, a charge reduction, ie the suspect agrees to plead guilty to a lesser crime than that actually committed. It does not expressly provide for sentencing pleas.

The Prohibition and Prevention of Money Laundering Act (as amended in 2010)

The Act proscribes money laundering and puts in place mechanisms for its prevention and investigation. This includes mechanisms for the disclosure of information on suspicion of money laundering activities by supervisory authorities and regulated institutions, forfeiture of property of persons convicted of money laundering, as well as international cooperation in the prevention, investigation and prosecution of money laundering.

The Financial Intelligence Act 2010

This is the main law dealing with intelligence-gathering for suspicious financial transactions. The Act establishes the Financial Intelligence Center (FIC), as the only designated agency responsible for the receipt, requesting, analysing and disseminating the disclosure of suspicious transaction reports. It is responsible for preventing money laundering, terrorism financing and other serious financial offences. It puts in place mechanisms for reporting and investigating suspicious financial transactions.

Public Procurement Act 2008 (As Amended by the Public Procurement (Amendment) Act 2011)

The Act establishes the Zambia Public Procurement Authority as the entity responsible for public procurement of goods and services (beyond a certain threshold). The Act is intended to enhance transparency and accountability in the public procurement process by putting in place standard procedures and practices. This would also ensure that the procurement process is fair to all stakeholders.

Existing mechanisms for addressing corruption and their potential effectiveness

The success of corruption intervention mechanisms in Zambia is to a large extent tied to the nature of the country´s political system. As explained in the political economy section above, Zambia has few effective countervailing mechanisms for holding the presidency in check. As a result, Zambia has a dominant presidential system which renders all other arms of government beholden to the executive. This has an effect when it comes to the fight against corruption, as it effectively entails that, although the country has adequate laws and institutions, their effective implementation is dependent on the political will emanating from the office of the president. As Professor John Hatchard has argued, in such a system much depends on the ‘tone from the top.’8fa38add0144

The dominance of the presidency in Zambia and its implications for accountability was succinctly stated in the African Peer Review Mechanism Country Report:

There is no real separation of powers between the principal branches of government and the executive is overly dominant, relatively unchecked and lacking accountability. The legislature is too weak and dominated by the executive for it to exercise effective oversight … the system of political patronage that permeates the entire organization of the government institutions renders all state institutions virtually beholden to the president.df2b071c42d4

Under this situation, the fight against corruption is and has largely been driven by the dispositions of the country’s presidents. While presidents Kaunda (1964–1991), Mwanawasa (2001–2008) and to some extent Sata (2011–2014) showed interest in fighting corruption, the regimes of presidents Chiluba (1991–2001), Rupiah Banda (2008–2011) and Edgar Lungu (2015–2021) showed limited interest. In the case of the Lungu regime, corruption seems to have degenerated into what journalist Michela Wrong has aptly called ‘State House’s system of authorized looting.’609eadc91b9e President Lungu, for example, was reported saying the following to senior government and ruling party officials in February 2018: ‘Ubomba Mwibala alya mwibala, tabatila kulya nembuto kumo’ [You can steal, but do not steal everything].b1b38034dded This was a classic case of sharing spoils among the elites with the aim of ensuring support for the president.

In August 2021, Zambia elected a new government that stood on a platform of economic recovery and a strong anti-corruption crusade. As already noted, the anti-corruption fight in Zambia is set by the tone of the president. In his inauguration speech, President Hakainde Hichilema promised:

The scourge of corruption has not only eroded our much needed resources, but it has also robbed us of the opportunity for growth. We shall have zero tolerance for corruption. This will be our hallmark. The fight against corruption will be professional and not vindictive. The institutions mandated to investigate and prosecute will be given unfettered autonomy to effectively and efficiently carry out their mandate without fear or favour of political bias.41677b50abf9

The new government and the strong anti-corruption rhetoric in the inauguration speech presents an opportunity for a new wave of anti-corruption interventions and corruption. If the new government keeps its word, this could see watchdog or anti-corruption institutions reinvigorated in the fight against corruption.

The measures discussed below should therefore be understood from this perspective of a dominant and overbearing executive.

Criminal prosecution

One of the available mechanisms for dealing with corruption is through the criminal prosecution of those involved in corruption. Many acts of corruption are recognisable crimes for which criminal charges can be preferred. Those convicted may face prison terms or other criminal sanctions.

The vigorous prosecution of officials for corruption has largely depended upon the commitment level of the president at the time. The most widespread and dedicated efforts at prosecuting officials was during the tenure of President Levy Mwanawasa (2001-2008). Because of the huge number of corruption cases the prosecution authorities had to deal with, the Mwanawasa government set up a Task Force on Corruption and hired a private specialised prosecutor, Mutembo Nchito, to handle the cases.1444fbe4787a Several high profile cases were prosecuted during this period, including former President Fredrick Chiluba, ministers and military generals.

To pave the way for Chiluba’s prosecution, the Mwanawasa government took the unprecedented move to ask parliament to remove Chiluba’s presidential immunity so that he could be prosecuted for cases of corruption he committed while in office.22b5e364f9cf Chiluba was duly charged and tried for multiple corruption cases. While the trial was still ongoing, President Mwanawasa died in office. His successor, Rupiah Banda, was accused of meddling in the case, leading to the controversial acquittal of Chiluba. Banda further disbanded the Task Force on Corruption on the grounds that it was a waste of public funds.

Mwanawasa’s crusade against corruption led to the arrest and prosecution of ministers and senior civil servants.e6f6f477ebae His successor, Rupiah Banda, did not have a similar zeal for addressing corruption. Soon after he assumed office in 2009, Banda disbanded the Task Force on Corruption and his government did not initiate any high level corruption prosecutions.103c346fa31d The most notable case during the tenure of Rupiah Banda was the prosecution of Henry Kapoko, a relatively junior human resources officer in the ministry of health, for cases of grand corruption relating to procurement of health supplies and services. Although this was a case of grand corruption, relating to the systematic looting of more than K30 billion (about US$ 10 million), and its complexity suggested the involvement of senior government officials, no senior government official was ever held accountable.ab17ccbad389

Michael Sata succeeded Banda in 2011, and Sata was elected on an anti-corruption platform. Although Sata did not fight corruption as aggressively as Mwanawasa had, he did send some clear messages in favor of prosecuting officials. Sata’s government lifted Rupiah Banda’s immunity, paving way for his prosecution. He dismissed some of his ministers accused of corruption, such as Ronald Chitotela and Rodgers Mwewa.ff2bfbdece7e

However, Sata had a short-lived presidency and died in office in 2014. His successor, Edgar Lungu, has been unresponsive to the fight against corruption, as he has made no commitment towards prosecuting corruption. The only successful high-level corruption prosecution was largely at the insistence of the country´s Western donors as the monies stolen in that case were British aid funds intended for a social cash transfer scheme. The case involved then Minister of Community Development, Emerine Kabanshi.25f1f7c32abf In other cases, the government has seemed more interested in immunising officials rather than prosecuting them. For example, Minister of Health, Chitalu Chilufya, was arrested and prosecuted for corruption in 2020. But instead of vigorously prosecuting the case, the Anti-Corruption Commission, taking an unprecedented move, went to Court to attest to his innocence, leading to an acquittal.10f07974106c

Asset declarations

One way of controlling corruption is through implementation of a robust asset declaration regime for senior government officials. Declaration of assets generally has a triple function. First, declaring assets protects honest public servants against false accusations of misuse of public funds. Second, it is a deterrent measure as it provides an early warning system of possible misuse of public funds and resources. Third, it provides compelling evidence of misuse of public funds and resources.8bf42db2bb77

In Zambia, asset declaration is governed by the Parliamentary and Ministerial Code of Conduct Act, which is the ethical code of conduct for Ministers and Members of Parliament. It, inter alia, requires those who fall under its jurisdiction to declare their assets, liabilities and income at set intervals. Declarations are made to the Chief Justice who keeps a register of the declarations that is accessible to the public.

Where the minister or member of parliament fails to make the declaration as required or makes a false declaration, anyone can write to the Chief Justice, requesting the Chief Justice to set up a tribunal to investigate the matter. This gives the Chief Justice a major gatekeeping role. A Chief Justice beholden to the executive, or not committed to the rule of law, will most likely not act on the complaints.

This has been the practice under the tenure of Chief Justice Irene Mambilima (2015–2021). She was asked on at least three occasions to set up tribunals to investigate misconduct of officials in line with the Parliamentary and Ministerial Code of Conduct, but declined to do so: In 2017, the Chief Justice refused to set up a tribunal to investigate allegations of corruption in maize exports involving agriculture minister Dora Siliya.957c75dc653d In 2019, the Chief Justice declined to set up a tribunal to investigate corruption allegations in the allocation of protected land involving Lands Minister Jean Kapata.4bceea08ec2f In 2021 Mambilima refused to set up a tribunal to investigate all the ministers and members of parliament who had failed to make declarations as required by the law.4a6ff0a71f8a

As these examples show, the mechanism of asset declaration can only work successfully where the gatekeepers are committed to the process and see value in it. Although this process was successfully employed under other former Chief Justices, Chief Justice Mambilima (2015-2021) has not used it successfully, as she used her gatekeeping role to block all applications to set up a tribunal to investigate allegations of corruption.

Oversight bodies

Zambia has several oversight and watchdog institutions. These include the Anti-Corruption Commission, the Public Protector, the Financial Intelligence Centre, the Drug Enforcement Commission and the Auditor General. Although all these institutions suffer from a lack of operational autonomy from the executive and are often subject to executive interference, two institutions appear to have been consistent and effective in exposing cases of grand corruption so far. These are the Financial Intelligence Centre and the office of the Auditor General.

The Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) is an autonomous public institution created to investigate suspicious financial transactions. It has been consistent in exposing cases of corruption since its creation. In 2016, for example, FIC reported that public officials or their associates received over K3 billion (about US$ 300 million) through kickbacks from public contracts.0888d2eef81e In 2017, the FIC figures more than doubled. It reported that politically exposed persons received more than K6.3billion (US$ 630 million) in kickbacks, mainly from infrastructure contracts.ef6a25bf7558 In the last five years, no investigation was initiated and no officials have been held accountable according to FIC reports.

Similarly, the office of the Auditor General has been forthright in exposing corruption. For example, responding to allegations of corruption in the infrastructure sector, the Auditor General in 2015 undertook an audit of the Road Development Agency (RDA), where it unearthed instances of massive corruption and wastage. The audit report documented numerous systematic shortcomings suggesting collusion between government officials and construction companies.df67156f3796 They include:

- Systemic delays in the engagement of supervising consultants for periods ranging from one to twelve months, resulting in projects being implemented without adequate supervision;

- Most of the projects commenced without detailed road engineering designs;

- The Road Development Agency (RDA) procured works of the unconstrained budget as opposed to the approved budget by parliaments;

- There were inexplicable variations on several contracts, ranging from 50% to 400%, which were beyond the allowed standard of 25%, and which significantly increased costs and for which RDA never sought approval of the Attorney General;

- Specifications were not adhered to leading to poor quality of work; and

- In many cases, the same contractor building the road was engaged to do detailed road designs for the same road0e61a98c52cd

The volume of these shortcomings suggests premeditation and not occasional lapses. The Auditor General, for example, found that 29 construction projects with an initial contract sum of K8,011,422,391 (about US$ 800 million) were procured and commenced without detailed designs.dbbda494c745

Although the office of the Auditor General has helped expose thefts, misapplications and abuse of public resources, once it has conducted an audit and issued its report, it lacks power to bring about compliance with public finance rules and regulations. It lacks power to sanction officials who have been found to have stolen, misused or misapplied public funds. It can only make recommendations to appropriate institutions and authorities on corrective measures to be undertaken. As a consequence, audit reports are routinely ignored by the executive.57299a4f6ea8

Because of the role the FIC and Auditor General have played in exposing corruption in the last five years, the government has several times tried to frustrate these two institutions. For example, in 2018, when FIC reported the substantial amount of kickbacks received by government officials, the government responded by withholding funding to the entity and by changing the FIC board.605ac858042b When the Auditor General exposed the abuse of resources in the construction sector, the government resorted to victimising the Auditor General by launching an investigation into alleged ‘irregularities’ and ‘lack of transparency’ in the office of the Auditor General.3df4adbc64c4

Civil suits

Sometimes to address corruption and recover public funds, it may be appropriate to institute civil cases. These are often instituted to recovery stolen money or follow the property purchased from the funds. The most successful use of this approach was the case against former President Fredrick Chiluba by the Zambian Attorney General in the United Kingdom.52ad383a7b07 From 1995 to 2001, the Ministry of Finance transferred large sums of money mainly into the Zamtrop account held by the Zambian government at the Zambia National Commercial Bank branch in London. The money was transferred for purposes of servicing or repaying the country’s external debts. Chiluba and his senior officers, including the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Finance and his intelligence chief, conspired to abuse these resources so that most of the money transferred for debt servicing was diverted for personal use. This money was then laundered through Meer Care and Desai, a law firm in the UK, using its client accounts, whereby Zambia officials would subsequently instruct the law firm to release the funds to support personal expenses. The money laundered in this manner was then used to buy enormous amounts of expensive clothes and luxurious properties in Belgium and South Africa. The UK´s High Court of Justice found that through this mechanism the culprits defrauded the Zambian people and found them liable to pay back a total of US$ 58 million.de0fe0ef62ef

In relation to Chiluba, the UK High Court had this to say:

At the end of the day he was the President at the top of the control of government finances. He was uniquely positioned to prevent any corruption. Instead of preventing corruption he actively participated in it and ensured it happened. It is difficult to find an adjective that adequately describes the failure on the part of FTJ [Chiluba]. He has defrauded the Republic. He has deprived the people over whom he was exercising stewardship on their behalf of huge sums of money which was supposed to be spent for their benefit. He has diverted those monies for wide ranging benefits of the Co-conspirators but has not shown restraint himself in the amount of money which he ‘plundered’ from the government coffers. It is a shameful series of actions and he should be ashamed.e7867dbce773

Civil remedies (via lawsuits) are also available to individual and corporate entities against an overbearing government that inordinately tries to interfere with the private sector. An interesting case involves the energy sector and was brought by the Copperbelt Energy Corporation (CEC), a private electricity company that supplies electricity to the mines. The suit was filed against the Attorney General, as representing the government.2b08d22f0ad3 One of the mines to which CEC supplied power is Konkola Copper Mines (KCM), a mine government recently repossessed from a private investor. KCM owed CEC more than US$ 144 million for electricity. When CEC tried to recover the money owed, the Minister of Energy in March 2020 reacted by declaring the transmission and distribution lines of CEC as common carriers, essentially allowing the government to control and use private property without the consent of the owners. Although the case is still ongoing as there is an appeal, the courts showed a possibility that they could be relied on to fend off an overreaching government in the private sector, by quashing the decision of the minister to declare government control over CEC’s infrastructure.

Societal norms

A non-legal remedy includes the establishment of societal norms, which means that corruption is publicly contested and becomes a precondition of government legitimacy and political longevity.

Scott Taylor8836e89fb0b1 captures the difference that the Chiluba trials made:

Certainly corruption continues in Zambia. Yet a different normative environment is slowly emerging, even within the bureaucracy. Moreover, at the presidential level, ‘the greatest benefit is laying a precedent’. In this respect, at least, it matters less that Levy Mwanawasa personifies the classical ‘big man’ than that he and those who follow his lead ‘to catch the big fish’ are binding themselves, consciously or otherwise, to an evolving set of norms and legal-institutional remedies that constrain future corruption.cdf7aa573e80

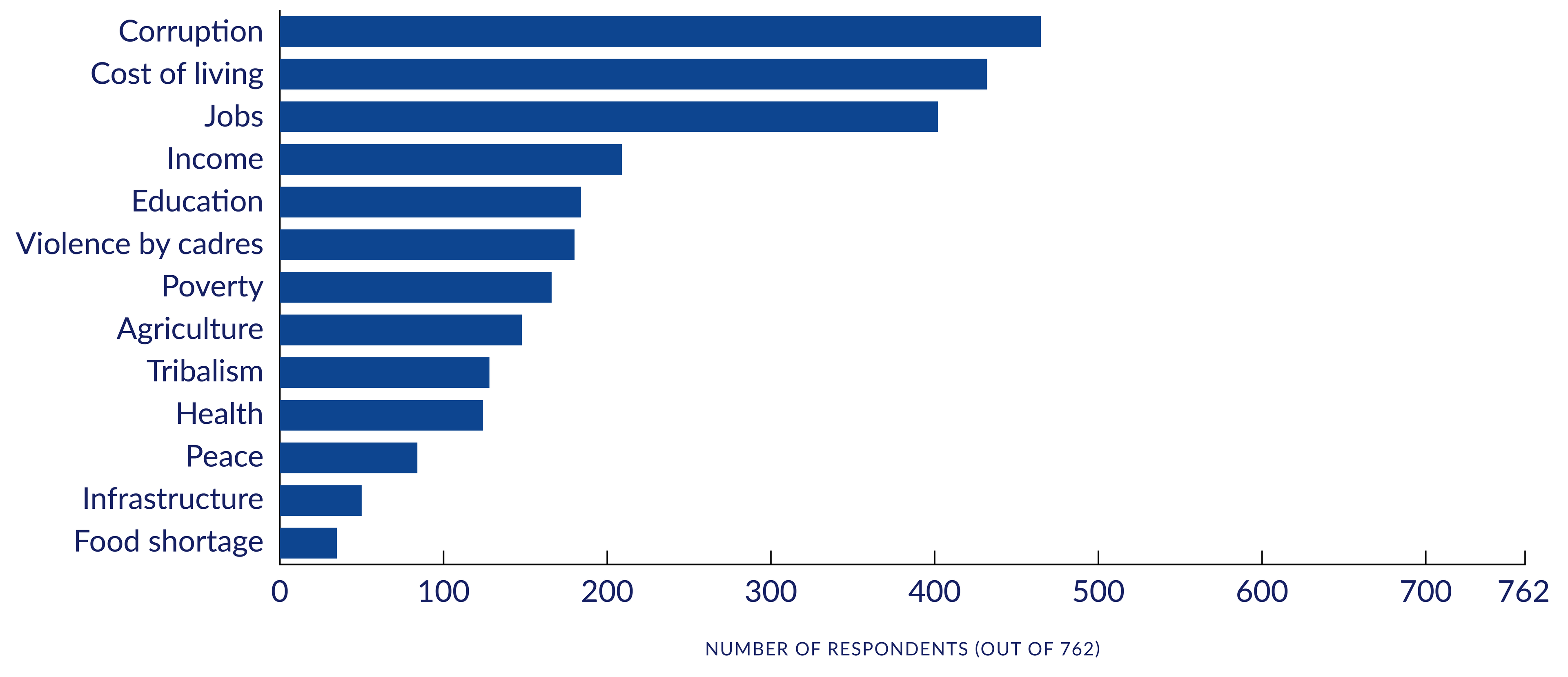

In fact, anti-corruption remains an important campaign platform for the opposition, as we can see in the current election cycle which ended on 12th of August 2021. Dissatisfaction with corruption features high in Zambia’s public sphere and therefore still matters in terms of political mandates (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Corruption and the cost of living are the top two issues facing the Zambian public

SAIPAR/BIEA survey May/June 2021 (based on 762 respondents)

The threat of debarment in the Zambian energy sector: a mini case study

There are very few successful anti-corruption mechanisms involving the energy sector. There have not been many high-level prosecution cases of officials or private sector leaders in the last five years. This could be due to the fact that prosecuting corruption in domestic courts requires a lot of political will. Without political will prosecuting corruption is unlikely to be sustained, especially since most of the corruption takes place in secrecy and only the state has an appropriate legal mandate and the mechanisms to access transaction details.

Although there have been very few high-level prosecutions, this does not mean that no interventions have been effective in fighting corruption in this area. This section highlights one mechanism that has successfully exposed cases of corruption in the energy sector, which is using debarments. Debarments have largely been applied to cases of corruption relating to procurement of services and projects in the energy sector. Three examples will be given for illustration.

Debarment, alternatively known as blacklisting or exclusion, is a process through which an individual or corporate entity is prevented or blocked from participating in tendering for projects for a specified period owing to previous involvement in corruption57f0f8e6d1dd Disbarment is now recognised as a significant mechanism for addressing corruption globally. It is thought that public resources are limited and must be put to good use. Contracting entities that are reliable and trustworthy ensure that public resources are applied to the right purposes.302776d35038

Where debarment is effectively implemented, it sends a message that access to the public procurement market is premised on compliance with laws and best practices. An individual or company subjected to debarment is likely to suffer tremendous economic loss and loss of reputation. This provides an incentive not to be involved in corruption.

In order to have an effective debarment mechanism, Professor John Hatchard3fba476d273f has proposed that the mechanism should have at least the following ingredients:

- Transparency: Individuals and companies should know clearly and in advance the kind of behaviour which will lead to debarment;

- Fairness: The debarment rules should allow the concerned individuals or companies to present their side of the story and be treated with fairness. The authorities should also apply the debarment rules uniformly and not selectively;

- Publicity: The outcome of debarment proceedings must be made public and widely publicised to ensure that potential contractors all over the world can easily undertake due diligence tests in contracting concerned individuals or companies;

- Proportionate penalty: There should be a sliding scale of punishment, taking into account the seriousness of the infraction and the size of the corporate entity involved; and

- Providing incentives to report: There should be built-in mechanisms for reporting, including for concerned companies (voluntary reporting), for example, a lesser punishment for a self-reporting company.8cbf15f8fa60

There is no comprehensive Zambian legal framework for the implementation of debarment. It is, therefore, unsurprising that the three case examples of debarment discussed below were at the instance of the World Bank. All three cases of debarment in Zambia by the World Bank involved corruption in procurement of contractors on energy projects by the state-owned Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation Limited (ZESCO).

The first case involves the Chinese firm Liaoning-EFACEC Electrical Equipment Company Limited (LEEEC). LEEEC was debarred by the World Bank in May 2020 for fraudulent practices relating to how it procured its contract with ZESCO on a project to enhance the transmission and distribution of hydro-electricity in Lusaka.42caf74ac64c The debarment makes LEEEC ineligible to participate in World Bank-funded projects for a period of 20 months.14d0a33afb31 As part of the settlement agreement, LEEEC agreed to undertake voluntary remedial actions, develop an integrity compliance programme, and fully cooperate with the World Bank on matters of integrity compliance.

The second example of debarment involved another Chinese company, Jiangu Zhongtian Technology Company Limited (ZTT), which manufactures and distributes fiber optic cables. It was debarred by the World Bank in May 2019 for its fraudulent conduct in the manner it obtained its contract with ZESCO on a project to improve the transmission and distribution of electricity in Lusaka. The debarment is for 20 months, disqualifying the company from participating in World Bank-funded projects during this period. As part of the settlement agreement, ZTT agreed to develop an integrity compliance programme and to continue to fully cooperate with the World Bank.d77c5a63933f

The final case example of debarment involves the French company, Alstom Hydro France and its affiliates. The World Bank debarred Alstom in 2012 for three years for payment misconduct or improper payment.0c6140d2bff7 It was established that in the process of obtaining a contract with ZESCO to work on a power rehabilitation project, Alstom paid a ‘consultancy’ fee to a company owned by a senior government official. As part of its settlement agreement, Alstom agreed to pay a restitution fee of US$ 9.5million and to continue cooperating with the World Bank in investigating the matter.fa7df2d360b6

Although these were successful cases of debarment, they also indicate limited political will for addressing corruption from the host country: No Zambian official involved in any of these cases was held accountable in Zambia. The import of these cases of debarment is that they address the demand side of corruption arising from the private sector. The success of these cases of debarment, however, may not apply to all players in the sector, specifically individuals and small entities without an international reputation to protect. Debarment is only likely to be a successful deterrent mechanism for corporate entities with global interests and/or a reputation to protect.fb26ed74e4d5

Impact of corruption on the renewable energy sector through the lens of Zambia’s renewable private sector

Based on the interviews with private actors and regulatory authorities in the renewable energy sector in Zambia, the following root causes and consequences of corruption are stated in their own words.

|

Poor leadership and low planning capacity in government, over-reliance on ZESCO |

|

As a result of a weakened Ministry of Energy, the private sector relies more heavily on plans by ZESCO, whereas ZESCO should just be another player in the field. |

|

High levels of corruption in procuring energy projects across the board and at the highest level. There is no transparency in ZESCO, it has not audited its accounts in many years. |

|

At policy level, government is sending mixed and worrying messages. While they say they want to open up the sector to the private sector, in reality, we saw a re-nationalisation of the sector. |

|

Government’s (fiscal) indiscipline and high levels of debt |

|

ZESCO is off taker as the national utility, but due to its credit worthiness and risk of default international lenders is not willing to fund projects. |

|

The high cost of doing business, due to exchange rate fluctuations, high interest rates and import duties creates other sources of corruption. For example, there is a significant business importing via Zimbabwe to avoid import tax on solar pumps imported through the agricultural sector, where solar pumps are tax exempt. |

|

The normalisation of bribes, like transport money for immigration and police officers, fees for headmen and chiefs, is a persistent problem. |

|

Multi-layered regulatory authorities and costs |

|

A number of processes have been put in place to prevent corruption. This has led to unforeseen outcomes, thanks to there being many layers of licensing and regulatory paperwork that a company may need. This then creates an incentive for the company to try to get around those regulatory hurdles in other ways. |

|

The politicisation of regulatory bodies and appointment of non-specialists to boards also poses problems, including inflated board member fees, leading to a cadre of ‘professional board members.’ |

|

Costs of running business remains high, which leads to corruption in order to circumvent costs. The regulatory institutions increase costs that are passed on to the consumer. |

|

The Rural Electricity Authority (REA) has established an Integrity Committee that has disciplinary codes. It submits quarterly reports to the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC). However, ACC does not take any of the report further for investigation, as it was rendered toothless under the PF administration. |

An overview of evidence on anti-corruption interventions and effectiveness in the renewable energy sector from comparable contexts

Several studies outline solutions to the problem of corruption in the renewable energy sector. Rahman870f51e3d5ca provides multiple possible avenues through which this corruption can be addressed. These include instituting enforceable transparency requirements on contracts and strengthening basic institutional structures. Komendantova et alfd83ddfb6ecf propose anti-corruption renewable energy reforms, such as reducing the number of bureaucratic hurdles and requiring in-depth verification and auditing of projects.

On the project preparation phase, Sobjakb0dd98c65003 suggests a few key policies to improve governance. First and foremost, she proposes dividing project preparation into four sub-stages. The rationale here is that this approach would allow officials to more methodically analyse and identify country-specific sources of corruption. She also suggests building capacity for project design within the relevant ministries and governments, improving the transparency of decision-making procedures, and using NGO-developed tools to evaluate project preparation.

Specifically, in the case of Zambia, Ndulo4f94bfaa9b51 reviews Zambia’s anti-corruption frameworks and proposes improving the transparency of its main anti-corruption agencies. His first suggestion is that they publicly and fully disclose their assets in order to combat conflicts of interest; secondly, he notes that the appointment procedure for anti-corruption agencies should be made more impartial and transparent so as to prevent appointees from being politically inclined. Most importantly, he suggests increased pressure from NGOs and the media to increase the political and societal will to fight corruption. These mechanisms would encourage the fair and impartial enforcement of anti-corruption laws, which, therefore, in turn would deter corruption in the first place.

Zambia could also attempt to emulate previously successful anti-corruption initiatives conducted by other countries and organisations. For example, the European Union’s Renewable Energy Directive demands that all relevant information and data be uploaded to an online public database for transparency purposes (European Lex). Additionally, the World Bank-funded Global Environment Facility (GEF) has invested billions of dollars in the renewable energy projects of emerging economies. This fund has successfully promoted further transparency and integrity in the renewable energy sector. Zambia could also establish non-partisan government agencies to take the lead on energy and infrastructure contracts.0c643935697b Sobjak57ce83649bd8 identifies Gabon as a successful example of this approach: Despite corruption being rampant throughout the government, the non-partisan Gabon Strategic Investments Fund has attracted investors due to its high professional standards and strong track record.

Importantly, there are other factors that must be considered when designing any anti-corruption reform for Zambia. Firstly, any anti-corruption measures must avoid falling into the same traps as those that have previously failed. Baker and Milne8cea78ff6fee find that Cambodia’s history of liberal reforms has failed to dispel corruption. Most Cambodian anti-corruption reforms emphasize checks and balances against corruption in the government itself. However, these reforms can shield governing bodies from political scrutiny while allowing them to continue consolidating their rule. Indeed, in Tanzania and Mozambique, governments have used anti-corruption reforms to cover-up further acts of corruption and profiteering.3e8980a3927e Instead, Zambia should adopt democratic anti-corruption reforms based on meaningful citizen participation in decision-making, which would render the government accountable to an entity other than itself.

This brings us to other stakeholders that can play their part. Increased pressure from NGOs to address corruption is needed. Consumer NGOs can make the link between corruption and the cost of renewable energy. Investigative media is needed to expose both sides of corruption. In addition, media can promote renewable energy so that it becomes seen as a ‘public good’ and thereby be promoted and defended. Donors may also play a role by increasing the visibility or reputational risks for junior companies, helping local authorities scrutinise locally based companies and avoid allowing decentralisation to become another layer of corruption risk, and reinforcing ethics codes through the REA and other institutions. But donors can also help companies adjust their standards and norms to the political environment in which they operate (ie culture of compliance), encourage shareholder or partner pressure to address corruption risks, promote actions on whistle-blower protection, and place a focus on anti-corruption in the upcoming deal with the IMF.

Way forward for Zambia

Taking the general lessons from above, combined with insights from the sector specific interviews, the following gaps and interventions are proposed:

Tackle Zambia’s constitution and the legal framework

- Reduce the executive powers of the president.

- Strengthen separation of different arms of government and enhance the autonomy and professionalism of oversight institutions.

- Harmonise the anti-corruption laws, enhance international anti-corruption legal standards in Zambia.

- Blacklist and debar corrupt (renewable) energy companies.

Enhance governance institutions, by domestic and international actors

- Create a culture in which it is deemed unacceptable to behave in a corrupt way and in which there is whistle blower policy.

- Enhance transparency in the way that financial transactions are reported.

- Strengthening the role of international organisations, beyond the western donors.

Advocacy for integrity by IFIs, civil society and media

- Learn from World Bank protocols that track procurement to implementation in order to fight corruption.

- Enhance the role of international organisations, like Actors in Minigrid Development (AMDA), Africa Clean Energy Technical Assistance Facility, Alliance for Rural Electrification (ARE).

- Civil society and consumer bodies should highlight the costs of corruption in the energy sector and their effects on costs to the end user, the consumer.

- Promote media campaigns to further the cause of renewable energy7c6909e90a4d and enhance investigative journalism to scrutinise corruption in the energy sector.

Adaption by small companies

- In a corrupt setting: avoid government tenders where possible.

- Offer specialised services that can be single-sourced; establishing trusted contact points within institutions.

- Provide symbolic gifts to chiefs and headmen.

- Leverage the local need for the product, ie ‘you need our investment’ arguments.

Need for more research

- Zambia’s political economy and legal analysis should be updated, especially in light of the recent change of administration

- The study could map the new regime type and new avenues of influence, look at the details of anti-corruption reforms and institutional capacities, and measure the effects of the business environment on off-grid companies.

- 2019.

- 2020.

- Gennaiolo Tavanoi, 2016.

- To protect their identity, we have kept the informants anonymous.

- International Financial Institution, interview, 22 June 2021.

- Hickey, 2019. See Hickey for more on this typology of political settlements. Briefly, power can be relatively ‘concentrated’ around ‘dominant’ ruling coalitions – ie Rwanda and Uganda – and the other scenario where power is more ‘dispersed’ within much more ‘competitive’ contexts (ie Ghana and Zambia).

- Tenderpreneurs: companies and individuals who profit from government procurement and tenders by being close to those in power.

- Chene, 2014.

- Rahman, 2020.

- Ndulo, 2014.

- Ndulo, 2014.

- Ndulo, 2014.

- This relates primarily to the right to own property. It was felt that SITET was too restrictive and an unnecessary restriction on the right to own property by public officers.

- Section 4 Anti-Corruption Act 2012.

- Ibid, sections 5 and 6.

- Ibid, Part III.

- Hatchard, 2014, 37.

- African Peer Review Mechanism, 2013, para 4.2.11.

- The Mast, 2018.

- Wrong, 2010, 184.

- Inauguration Speech by The President of the Republic of Zambia His Excellency Mr Hakainde Hichilema, 24 August 2021.

- Ryder, 2011, 4.

- Fredrick Jacob Titus Chiluba v Attorney General Appeal No. 125 of 2002.

- Lusaka Times, 2020.

- Lusaka Times, 2009.

- Notably Katele Kalumba, who was Minister of Finance; Stella Chibanda, Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Finance; Kashiwa Bulaya, Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Health; Richard Sakala, Special Assistant to the President; and Professor Benjamin Mweene, who was Secretary to the Treasury. Military generals were also not spared: the Army Commander, Geojago Musengule; Air Force commander, Christopher Singogo; National Service Commander, Wilford Funjika; and Director of the Intelligence Service, Xavior Chungu, were prosecuted for various cases of corruption.

- Mwebantu, 2013.

- Lusaka Times, 2020.

- Lusaka Times, 2021.

- Hatchard, 2014, 40.

- The Mast, 2021.

- Digger News, 2019.

- Lusaka Times, 2017.

- Iibid, 10.

- FIC, 2017.

- Auditor General, 2017.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 18.

- Chanda, 2003, 23.

- Daily Nation, 2018.

- Newsdiggers, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Hatchard, 2014, 34 and 189.

- Attorney General of Zambia v. Meer Care and Desai and other [2007] EWHC 952 (Ch), para 443.

- The People v. Attorney General and The Energy Regulation Board (Appeal No. 33/2020) [2020] ZMCA 86.

- 2009.

- Taylor quoted in van Donge. 2009, 89.

- Ibid.

- Rahman, 2020.

- 2014.

- Ibid, 264.

- Ibid.

- World Bank, 2020.

- World Bank, 2019.

- Ibid.

- World Bank, 2012.

- Dougherty, 2015, 10.

- 2014.

- 2020.

- 2018.

- 2014.

- 2018.

- Martin et al 2014.

- Sjobak 2018.

- 2019, 1.

- From interview: ‘If we take the case of rampant load shedding in 2016 and 2017; the media highlighting the importance of solar equipment and educating the masses, it led to increases in purchases.’