Are anti-corruption measures included in peace agreements?

Corruption, or ‘the abuse of entrusted authority for private gain’, thrives in war-to-peace transitions and is exacerbated by weak state institutions and large influxes of international funding.d4acf1c5a6d7 An intensification of corruption after a political settlement is reached can rapidly undermine peace and plunge a country back into violent conflict.5fbb40b26ff2 The design of a negotiated settlement laid out in a peace agreement – a ‘formal, publicly available document, produced after discussion with conflict protagonists and mutually agreed to by some or all of them, addressing conflict with a view to ending it’2eed09b5b534 – has been linked to post-war stabilisation. The process of negotiation, setbacks, and the agreement of terms by conflict parties collectively forms a peace process. This is largely understood as a ‘structured attempt to resolve radical disagreement between conflict parties’,7a937d022999 which varies considerably in scope, content, complexity, and goals. However, anti-corruption measures established within peace processes will not guarantee that corruption cannot become endemic in the reformed political settlement (see Box 1).645a9532975b

This U4 Issue presents evidence on how often anti-corruption provisions appear and are used in peace processes, interpreted through peace agreements over a 34-year period. Using data from the University of Edinburgh’s Peace Agreements (PA-X) Database,2b32199b315e it analyses the prevalence and content of explicit anti-corruption provisions identified in 140 peace agreements signed as part of 62 peace processes between 1990 and 2023. The analysis does not include negotiated outcomes that contain implicit anti-corruption provisions, such as strengthening institutions and the rule of law.3e7186dc9e41

Box 1: Corruption in war-to-peace transitions

Post-war corruption can take many forms – from elite cronyism to endemic corruption affecting large segments of the population. After successive peace agreements in South Sudan, ‘embezzlement, bribery, and misappropriation of state funds by political elites’ remained merely the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of corrupt practices (OHCHR 2021). Whereas, in Afghanistan, ‘administrative bribery was singled out as placing the greatest burden on the economic wellbeing of Afghan citizens’ (UNODC 2012, p. 7). The type of corruption depends on which actor holds entrusted authority. For instance, after the 2017 liberation of Mosul, Iraq, non-state militias requested bribes from the displaced to ensure their ‘safe’ return (SIPRI 2019, p. 1). Peace tends not to influence the level of corruption and the anti-corruption measures established within peace processes do not guarantee that corruption will not become endemic (Jarvis 2020, p. 169). In countries such as Afghanistan and Nepal, back-room deals and organised crime operated as alternative conflict-resolution mechanisms (Jarvis 2020; Goodhand 2008). It is argued that the use of power-sharing may increase the prevalence of corruption in the post-settlement phase (Haass and Ottmann 2017). Power-sharing in the executive may be used by negotiators to deter spoilers and ‘buy the peace’ and allow warring parties to secure rent through state office – for instance, as seenin the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (early 2000s) and Liberia (1993–2001) (Cheng and Zaum 2008, p. 303–4.). Such systems do not promote a ‘positive’ (sustainable) peace but can promote a quasi-stable situation of ‘no war, no peace’ lasting many years (Cheng and Zaum 2008, p. 303–4).

With heightened calls to incorporate an anti-corruption agenda in peace processes, the focus on explicit anti-corruption provisions allows us to establish a precedent of how anti-corruption measures have been incorporated in peace agreements. This also enables us to see the extent of these practices, which has not been documented in the literature. The emphasis is not on identifying best practice0cdc185b2586 – the examples used are decontextualised. Rather, the aim is to identify the content and language of anti-corruption to improve understanding, create an instructive body of case study examples, and establish a precedent for practitioners, which has been lacking.f096aac0af0a The analysis highlights the gaps in previous approaches and suggests where additional efforts can be made in the intersectionality of anti-corruption measures, such as in regard to broad societal participation and gender inclusion.

This U4 Issue does not seek to argue that including anti-corruption measures in peace agreements should be the norm in every negotiated peace process. The absence of anti-corruption provisions in peace agreement texts is a result of various complex factors, including that the anti-corruption agenda may be pushed down to the technical level or into negotiation channels that run in parallel to the ‘political track’, such as the ‘constitutional track’. Also, anti-corruption measures may be explored in other fora of negotiation that operate alongside the peace process, including the judiciary or the legislature.

The research questions guiding this inquiry are:

- How are anti-corruption initiatives incorporated and conceptualised in peace processes?

- How often do peace agreements provide for anti-corruption and at what stage of the negotiations?

- What type of anti-corruption approaches are provided for?

To answer these questions, the U4 Issue draws on data from the Peace Agreements (PA-X) Database that assembles 2,055 peace agreements from between 1990 and 2023. The database includes 156 agreements that address ‘corruption’ – which pertains to ‘any mention of measures to address corruption, including references to auditing (eg the establishment of an auditor general) and mechanisms for “transparency and accountability.”’1fc6ab959fbd Using the methodology of Braun and Clarke (2006), corruption references where further coded into 32 sub-categories related to anti-corruption initiatives and rhetoric.d8b56fc697b7 The final dataset consisted of 140 agreements signed as part of 62 different peace processes (listed in Annex 2). Each agreement has affiliated metadata which factors into the analysis: country, name of agreement, date, agreement type, peace process name, and so forth. Less clear is the analysis of ‘provisions’, which is used in this U4 Issue to broadly refer to articles, sections or paragraphs in a peace agreement. A provision can vary widely in detail and scope – from multiple paragraphs to a short bullet point – and so there is no attempt to provide any descriptive statistics concerning the number of anti-corruption provisions. Of the 140 agreements analysed in this scoping study, most (112) are ‘intra-state’ related to civil wars, with 14 agreements are ‘inter-state related to intra-state conflict’ and 12 agreements are ‘inter-group’, (that is, local or sub-state). Two agreements are ‘inter-state agreements’.

The following section provides an overview of the prevalence of anti-corruption provisions in peace agreements over a 34-year period. It further outlines when anti-corruption provisions are most likely to be incorporated into a peace process.

Anti-corruption measures in peace agreements 1990–2023

Peace processes are opportune moments to seek reform in the political settlement of a post-war country or region. Aspects confirmed in a peace agreement – such as the foundation of rule of law, and strong public financial management – can help to establish strong institutions and systems of good governance. This can boost the legitimacy of a process and help to avoid conflict recidivism.3c80a9cfe865 The inclusion of anti-corruption provisions early in peace processes can help to legitimise the agreement’s implementation and stabilise conflict. Within policy circles, anti-corruption measures are one of the avenues explored in contemporary peace processes when dealing with how to engage non-state criminal actors (such as cartels).d7b8b519216a Also, target 16.4 of UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 seeks to ‘significantly reduce illicit financial (and arms) flows by 2030, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organised crime.’ Integrating anti-corruption initiatives into peace settlements, therefore, ranks highly on practitioner and scholarly agendas worldwide.4c2f8e2b96b2

Of 171 peace processes, anti-corruption provisions appear in 62 (see Annex 2). This means that 36% of peace processes mention anti-corruption, but in two-thirds of these processes, provisions are limited in scope or largely rhetorical. Only ten peace processes contain a broad range of coded provisions that address multiple aspects of anti-corruption (15–44 codes) (see Box 2); 13 processes contain a mid-tier range of coded provisions across agreements (6–14 codes),4fb76018701b and 39 processes contain five or fewer codes.01e5378d9862

Box 2: Agreements with detailed anti-corruption provisions

Burundi

Arusha Accords, 2000

Colombia

Solución al Problema de las Drogas Ilícitas, 2014

Agreement on Security Guarantees, 2016

Final Agreement & Agreement on Security Guarantees, 2016

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Sun City Agreement, 2003

Transitional Constitution, 2004

Libya

Libyan Political Agreement, 2015

Nepal

Constitution of Nepal, 2015

Somalia

Provisional Constitution, 2012

South Sudan

ARCSS, 2015

R-ARCSS, 2018

Yemen

NDC Outcomes Document & Peace and National Partnership Agreement, 2014

Zimbabwe

Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (no. 20), 2013

The post-2000s donor agreements on Afghanistan included a broad scope of anti-corruption provisions across multiple agreements, but no particular agreement stands out in regard to anti-corruption content in contrast to the processes above.

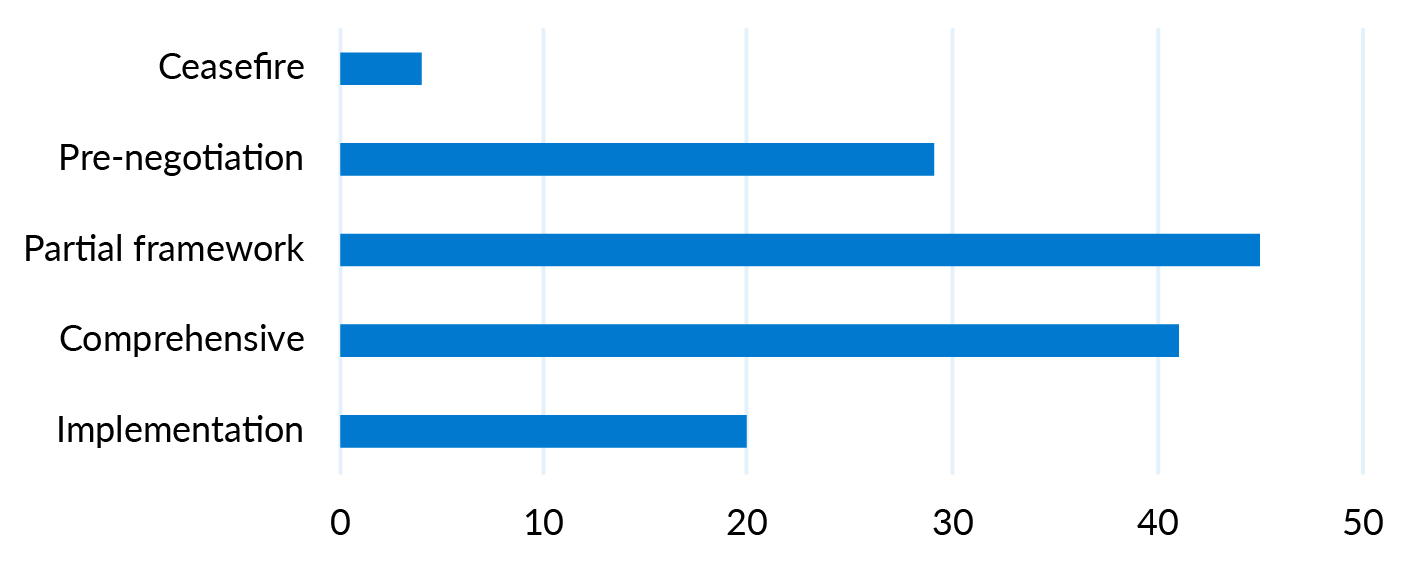

On average, 7% of all peace agreements mention anti-corruption. This reflects that it is not necessary or prudent to include anti-corruption in every agreement during a peace process. Of the 199 comprehensive peace agreements on PA-X, 41 (21%) contain anti-corruption provisions. This indicates that anti-corruption measures are nearly three times as likely to be incorporated during stages aimed at broad institutional reform.

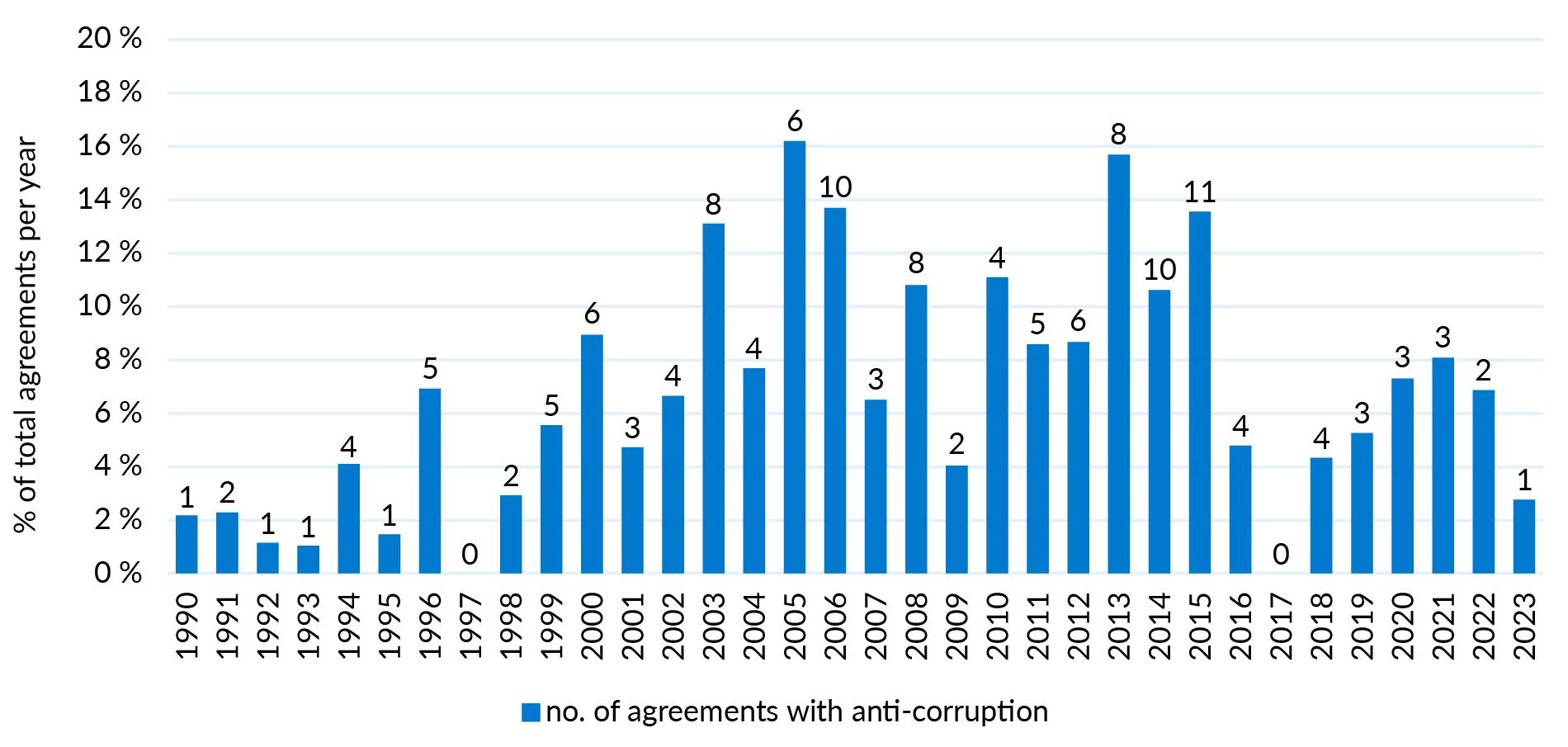

The adoption of anti-corruption initiatives in peace agreements was most frequent between 2003 and 2015 (see Figure 1). In general, the prevalence of anti-corruption provisions varies across different time periods, and a larger number of agreements containing detailed anti-corruption clauses were signed after 2010 (see Box 2).

Figure 1: Percentage of agreements containing anti-corruption provisions per year

The drop in peace agreements containing anti-corruption provisions in the past decade (see Figure 1) is related to factors such as: a proliferation in the marketplace of states’ mediating agreements (many of them illiberal); a move away from UN negotiated peace process frameworks (Libya, Yemen, Syria, and so on), which has pushed negotiations to away from the national level to the subnational level; and a drop in the number of comprehensive peace agreements signed since 2015.487c76cd4f98

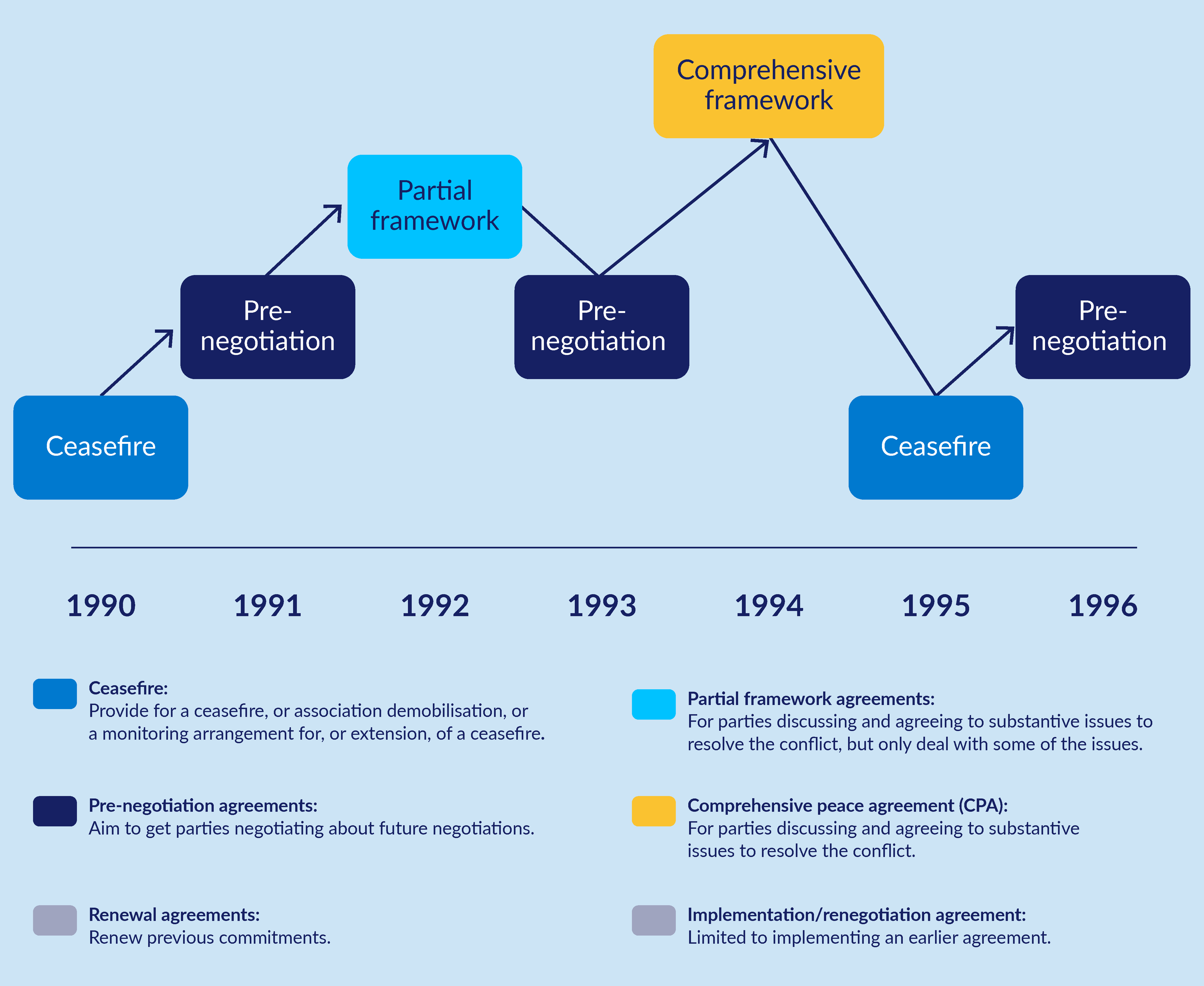

Anti-corruption initiatives in peace mediation stages

In the peace agreements that mention anti-corruption, 61% of provisions appear in framework agreements and comprehensive peace agreements. These agreement categories represent the more substantive peace agreement types that include extensive reforms with broad societal implications. This indicates that discussions of anti-corruption require greater levels of confidence between mediating parties that must sit with one another over longer periods during the drafting process.

Anti-corruption initiatives and references are not usually incorporated into other peace agreement types (see Figure 3). In ceasefire agreements, corruption provisions may be included ad hoc as confidence-building measures, but this is uncommon. One example appears in Myanmar’s 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement which commits to planning projects in local communities according to the standards of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Anti-corruption provisions in ceasefires could have the potential of increasing transparency, but are unlikely to increase accountability due to a lack of overall governance in place. The absence of anti-corruption provisions in ceasefires further highlights the sensitivities of including anti-corruption measures and potential weaponisation of such provisions against opposition parties. Ceasefires can also include a prohibition on inflammatory rhetoric between conflict parties. Under these terms, accusations of corruption could be interpreted as a ceasefire violation. Therefore, instead of using specific anti-corruption clauses, a ceasefire may represent an opportunity to outline implicit provisions for anti-corruption such strengthening good governance.

Figure 2: Peace agreement types and non-linearity of sequencing

Credit: Source: Drawn from Bell et al. (2024b). by-nc

Figure 3: Anti-corruption provisions across peace process stage

Half of pre-negotiation agreements that have anti-corruption provisions mention anti-corruption rhetorically as a principle to be incorporated in negotiations. In some instances, in preparation for further discussions, a pre-negotiation agreement may provide an understanding of how corruption has contributed to a conflict – such as the following example from Nigeria:

‘… the Berom people with the connivance of the Plateau State Government (Nigeria) and the police have consistently [limited Fulani rights] through confiscation of their legally acquired lands and orchestrated attacks.’5a0f6aa096a1

Overall, anti-corruption provisions are only found in 29 of the 537 pre-negotiation agreements included on the PA-X Database, indicating that it is not a widespread practice.

Why aren’t there more anti-corruption references in peace agreements?

The relative absence of specific references to anti-corruption in peace agreement texts highlights multiple tensions between the anti-corruption and peace mediation agendas. First, these limitations show the sensitivities surrounding the integration of anti-corruption among negotiating parties. This can be circumvented by avoiding the language and terms of anti-corruption and instead relying on the interpretation of good governance, reforming public management, and instituting competent checks and balances.

Second, the absence of anti-corruption provisions may indicate a desire among certain actors to avoid oversight during the transitional phase. This could be to secure their position with the state’s political elite networks through cronyism. It could also involve purchasing alliances through mutually beneficial (and corrupt) business opportunities. Substantive anti-corruption reforms and enforcement mechanisms are usually contained in comprehensive peace agreements including ‘peace agreement constitutions’.e2b12cb2245c This may indicate that, even without high levels of trust, conflict parties are willing to discuss and adopt anti-corruption measures when they have sufficient confidence in the process.This coincides with the moment when a process is more inclusive, indicating that perhaps expanding beyond politically elite groups helps place anti-corruption initiatives higher on the mediation agenda. Other factors must be considered, including a mediator’s sensitivity to good governance concerns, civil society pressures, and the increased involvement of multilateral actors in constitution-building.

Third, when included in peace agreement texts, ‘corruption’ is usually interpreted as an ‘illegal act’. The appearance of codes of ethics and other anti-corruption principles not defined as legal or illegal highlights how some conflict parties attempt to institute anti-corruption as a set of norms in an attempt to overcome partisan definitions of corruption that can be mobilised to de-legitimise opponents and potentially undermine peace gains.

Types of anti-corruption content in peace agreements

In addition to descriptive provisions where agreements spell out specific practices that are considered corrupt,bb8074faa58b there are four main types of anti-corruption provisions.

The two most prevalent types relate to the ‘implementation of anti-corruption measures’ and ‘commitment to anti-corruption reform in specific sectors’ (see Table 1). The third-largest category relates to provisions that give rhetorical commitments to anti-corruption. The smallest category relates to dealing with past instances of corruption and asset recovery.

Table 1: Frequency of coding for anti-corruption sub-categories

|

Provision type |

No. of peace agreements |

|

Implementation of anti-corruption measures |

98 |

|

Commitment to anti-corruption reform in specific sectors |

79 |

|

Rhetorical commitments |

48 |

|

Dealing with past corruption, asset recovery |

11 |

An overview of coding and frequency of codes is available in Annex 1. ‘Implementation of anti-corruption measures’ includes provisions on legal reform, use of international law, ways of enforcing anti-corruption measures, how third parties are incorporated, as well as tools such as codes of ethics, vetting, disclosure procedures and laws, public awareness and training, and the use of conditional funding. Provisions including ‘commitments to anti-corruption reform’ usually commit to reforms in the civil service, private sector, electoral reforms, judicial, and instituting anti-corruption in economic interest are as such as illicit financial flows and natural resource extraction. ‘Rhetorical commitments to anti-corruption’ include general statements committing the parties to the principles of anti-corruption and can stand as single provisions or appear alongside more substantive provisions. Last, provisions ‘dealing with past corruption’ seek to implement retrospective justice in regards to corrupt activities, including the recovery of assets.

Commitments to transparency

Commitments to transparency are among the most prevalent clauses. References are most often rhetorical – they do not include implementable actions – but in several cases they may include clauses specifying the disclosure of funds by senior officials; reporting requirements by public bodies; the implementation of freedom of information acts and other similar transparency regulations; and guarantees of media access to information.

For example, the 2014 National Dialogue Conference Outcomes Document from Yemen notes, that:

‘…the law shall provide guarantees to access information by citizens, [civil society organisations] and the media, use of such information and to perform a role in monitoring and enhancing aspects of transparency in public policies, administrative actions, especially those related to finance to enable citizens, political parties and stakeholders [to perform] their role in the process of control and accountability.’

Legal reform

Legal reform to promote anti-corruption is also among the most common provisions relating to implementing an anti-corruption agenda. Many provisions are limited to signalling intent to conduct legal reform to bolster anti-corruption principles. A 2006 agreement from Nepal, for instance, notes that ‘policies shall be adopted to take strict actions against those who, occupying governmental positions of benefit, have amassed huge properties through corruption’.4b95b5c8e7f2

Other texts contain regulations that will become law through ratification by the legislature or as a constitutional amendment (extrajudicial or inline with constitutional parameters).3acbce5b90a3 Prohibitions may also include practices that are identified as corruption, such as the following example from Cibitoke province, Burundi, which notes: ‘do not request pots of wines, because they are in fact of corrupt practices’.21c3f1c35694

Legal reform promoting anti-corruption can touch on any area where corruption is identified. This includes procurement and tendering, election funding, taxation, governance of state properties, and regulation of financial services. One specific case from Cote d’Ivoire relates to legal reform to bolster anti-corruption in the regulation of citizenship.cb789ceab2dc Provisions also regularly established to ensure transparency, due process, and to avoid conflicts of interest, such as by prohibiting senior officials’ family members from working in customs and taxation, and prohibiting senior officials from appointing civil servants.52336b2a284e

Sectoral reform

Multiple agreements commit to anti-corruption reforms in specific sectors of the political system or economy. Two main aspects emphasised in the public sector were the ‘civil service’ and ‘systemic’ – that is, non-specified inter-sectoral reform. In Guatemala, for instance, an agreement underscored the importance of the state being run by a ‘skilled labour force’, drawing links between civil service professionalism and integrity.25efc3fda750 This is further reflected by 15 agreements that highlight the use of codes of ethics, honour, or professionalism for senior officials and members of the civil service, thereby promoting cultures of integrity. Other agreements attempt to tackle the underlying politicisation of state structures through the verification of civil servant backgrounds in contexts as diverse as Colombia, Iraq, and Mozambique.97eaaac305d9

Table 2: Commitments to sectoral reform

|

Public/economic sector |

Sector |

Coding frequency in 140 peace agreements |

|

Public sector |

Civil service, public administration |

23 agreements |

|

Systemic reform (non-specified sector) |

17 |

|

|

Security sector incl. police, gendarmerie, military |

14 |

|

|

Judiciary |

12 |

|

|

Elections |

11 |

|

|

Economic sector |

Private sector and procurement mechanism |

16 |

|

Natural resource extraction |

10 |

|

|

Finance and illicit financial flows |

8 |

Establishing enforcement bodies

The most frequent provisions include establishing (or reforming) anti-corruption enforcement and oversight bodies. The ‘creation of a committee to fight corruption and financial mismanagement’, one agreement from Mali notes, is central to the promotion of ‘genuine national reconciliation.’cb7ec196cbb3 There are three main types of enforcement body relating to audit, corruption commissions, and budgetary oversight. Other less common means of anti-corruption enforcement (the ‘other’ category) include courts and ‘self-enforcement’ or ‘self-monitoring’ (mostly found in the security services).

- Auditing and compliance bodies

Peace agreements (or legal reforms) may establish and enable an Office of General Audit and provide for its internal governance, checks and balances, and processes of recruitment, censure, or replacement. Audit bodies are often set up alongside other anti-corruption mechanisms. In Afghanistan, parties outline a comprehensive roadmap for the establishment of several anti-corruption bodies. Provision for creation of an Audit Law means they can also rely on external audits of the Control and Audit Office.7598c10271a1 Other agreements opt to reform existing auditing bodies or their mandates, such as agreements from the Central African Republic, Comoros, Gabon, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Nepal, Sri Lanka, South Sudan, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. Rarely are the intelligence services placed under the purview of a state audit authority.742cdcb73630 No agreement provides for an audit during the war-to-peace transition as a means of increasing confidence in the peace process.

Power over the Auditor General’s Office is particularly fraught in circumstances of territorial power-sharing. In Liberia’s 1993 Cotonou Agreement, the position of Auditor General was subject to a power-sharing arrangement. In Sri Lanka, the Tamil Tigers argued for autonomy of the Auditor General in the northeast.7f0e4703c7ab Meanwhile, in an agreement between the Autonomous Bougainville Government and the Papua New Guinea National Government, the mandate of state audits is discussed in the context of the larger territorial power-sharing arrangement. In the final agreement it was stated that Port Moresby could withhold budgetary funding if there were cases of abuse, misuse, or misappropriation of public funds in Bougainville that were not sufficiently dealt with by local officials.5eef7eb5b4e7 - Budgetary oversight

Provisions on budgetary regulation, reform and oversight aim to counter corruption by strengthening public management. A common aspect in multiple agreements relates to transparency and accountability, as well as the prohibition on multiple budgets or supplementary budgets. Addressing imbalances in the public budget and rationalising expenditures is seen as an important pillar in the anti-corruption reforms envisioned by the 2014 Peace and National Partnership Agreement in Yemen.6f4f33189342 - Anti-corruption commissions

Implemented through peace accords, such commissions are varied in structure and mandate. Some, such as the Kenyan Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, are not strictly limited to anti-corruption. They can investigate a broad spectrum of issues, including human rights violations.f10011a3d053 Most agreements demonstrate two main modalities: either they provide a generic stipulation for the establishment of an anti-corruption commission without additional detail; or comprehensive peace agreements may include extensive provisions outlining the structure, mandate and bylaws governing such an entity, often in parallel with other necessary reforms.0c28dac95fa4 South Sudan’s 2018 Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) provided for the review of the 2009 Anti-Corruption Commission Act. It emphasised the institutional independency of the commission and its protection from political interference. It also stipulated the harmonisation of the Anti-Corruption Commission’s work with the Ministry of Justice, the police force, and the Public Prosecution. - Other means of enforcement

In addition to auditing and anti-corruption commissions, agreements may establish other pathways of enforcing anti-corruption regulations, including the establishment of anti-corruption courts, and strengthening the Public Prosecution, among others. Several agreements seek to harmonise anti-corruption efforts between the various modalities identified in the sections above with additional ministries and entities. In Mozambique, the parties established the Commission for Monitoring the De-Partisanship of the State. In Colombia, the parties committed to establishing an Integrated Information System as well as an inter-agency group to combat corruption in the implementation of the 2016 Final Agreement.1f0c9bd1cc12 Agreements may note how anti-corruption bodies are located in the hierarchy of the state, and the branch of government – executive, legislative, judiciary – they should coordinate with. Alternatively, they may establish chains of reporting and ombudsmen to allow for whistleblowing, and other protections. Sectoral commissions – particularly electoral commissions – may be responsible for deterring corruption in their particular sector.* Several agreements stipulate that the police will combat corruption.e92f01b8b54b

Involving third parties

Third-party involvement in anti-corruption efforts range from active involvement74e6de8ba930 to operating as independent auditors.db762ff2c05f In the context of government contracts, the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement provides for collaboration with ‘independent international experts’ if necessary (p. 29). The international community may more generally be identified as the guarantor of the implementation process. Third parties may be called on to safeguard vulnerable communities from corruption, including displaced persons (especially women).b226b581217c

Third parties mentioned in agreements include the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, international groups of ‘friends,’b02b52bf1165 UN organisations or missions including the United Nations Development Programme or African Union Mission in Somalia, or international non-governmental organisations. For instance, in South Sudan, parties commit to ‘joining the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative to enhance accountability in the management of the petroleum and mining industry.’ea26f08c7ca1 A third party to anti-corruption monitoring or enforcement may also include representatives from the international or local media.02635e1d814c

International law

Only a handful of agreements call for anti-corruption legislation to align with international agreements.783fe54ec240 Five agreements from Afghanistan and South Sudan reference the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) directly and Afghanistan provides a timeline for the convention’s ratification. Afghanistan also stipulates the implementation of recommendations by the Financial Action Task Force – Asia Pacific Group on anti-money laundering and combating terrorist financing.d0cdc2538d86 The Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) and its revised R-ARCSS agreement provide for South Sudan’s accession into UNCAC as well as the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption. This echoes the practice of referencing UN Security Council resolutions and international conventions in peace processes regarding other areas of strategic concern, such as affirming the rights and inclusion of women.

Broadening participation

One of the key requirements for combating corruption is public investment in anti-corruption measures to ensure that people have access to the necessary tools.22bca48c9f39 As noted by the 2013 Participacíon Política agreement in Colombia:

‘Citizen participation and control are essential to ensuring the transparency of public administration and that resources are used correctly. It is also an important part of making progress in the fight against corruption and the penetration of criminal structures in public institutions.’ab0e622751b8

Broad societal participation is noted as a barrier to corruption. It achieves this through monitoring and oversight, and opening public channels of communication about corruption (such as via ombudsmen). Despite this, participation does not intersect with anti-corruption in many agreements. In some contexts, members of civil society may be recruited to national anti-corruption bodies.7aa8cf3abe9c In the DRC, for instance, civil society representatives were appointed to anti-corruption institutions during the period of transitional government. Alternatively, agreements may stipulate that the planning of activities likely to impact local communities – such as natural resource extraction – requires the participation of opposition groups to ensure transparency, as was the case in Myanmar.

Incorporating gender issues

Gender issues are mostly incorporated in anti-corruption measures through generic references to ‘men and women’, with a few exceptions. The 2018 R-ARCSS agreement from South Sudan states that women’s organisations should be involved in policy advocacy against corruption. In Colombia, strengthening the justice system to ensure transparency and deter ‘private justice’ is recognised as contributing ‘to ensuring the effective administration of justice in cases of gender violence, free of gender-based stereotypes or sexual orientation’.18a3ee7a896f The agreement further emphasises the protection of women, children and adolescents affected by criminal organisations. A similar provision relates to displaced women in the 2006 Darfur Peace Agreement.0bfacc9cf9c5

The 2003 Sun City Agreement from the DRC places ‘clientelism, sexual harassment, bribery, [and] the abuse of power’ on its list of ‘anti-values and non-transparent practices’. The sandwiching of ‘sexual harassment’ between otherwise well-established acts of corruption implies a recognition of ‘sexual corruption’ – that is, when an entrusted authority abuses their power to obtain a sexual favour in exchange for a service or benefit.* An agreement may stipulate a quota for women’s participation in anti-corruption bodies, such as the Interim Anti-Corruption Commission in Somalia or the Governance Reform Commission in Liberia.ddfa22d452f4

Other anti-corruption measures

Agreements may include several additional methods for promoting anti-corruption. The most frequent is the establishment or reform of a ‘code of ethics’, which appears in 15 agreements. The next most common aspect includes the dismissal or impeachment of civil servants and political leadership on the grounds of corruption and incompetence. This is usually pursued by a body in a different branch of government (that is, a judge may be dismissed by the president; the president dismissed by the legislature, and so on). On rare occasions, an agreement may provide for a purge:

‘As a matter of urgency and priority, the Broad-based Transitional Government shall rid the administrative apparatus of all incompetent elements as well as authorities who were involved in the social strife or whose activities are an obstacle to the democratic process.’ae03bc484306

Other methods include the vetting and disbarment of political figures involved in corruption, or placing conditions on funding (from national to regional government, or from UN to governmental) based on adherence to anti-corruption principles. A handful of agreements provide for awareness campaigns, training, or educational programmes aimed at deterring corruption. As noted in a 2002 agreement from Sudan: ‘bribery must be eliminated by civil authorities at all levels […] through good policies, conducting political rallies, seminars and workshops, mass enlightenment and civic education.’ee0e6d0d7ab7

The potential for improving anti-corruption measures in peace mediation

Despite the inclusion of anti-corruption measures in a third of peace processes over the past 34 years, their scope is often limited and unambitious. This highlights the potential and the challenges that practitioners face, and the gaps in existing practice. Throughout the dataset, there are no agreements with anti-corruption provisions related to the health, environmental, migration, and education sectors. Only a handful of agreements touch on the areas of asset return, illicit financial flows, gender, procurement, resource extraction, and customs. The absence of anti-corruption initiatives highlight a paradox inherent in peace processes in that there is a risk that the new political settlement emerging after an agreement is signed helps facilitate the capture of the state by the political elites making the deal. Another reason is that certain groups fear that anti-corruption measures may be used against them, thereby jeopardising greater support for the peace process.1e57fdc82b08 Conflict parties and mediators may also interpret corruption as an issue that can be handled separately to, or after, the mediation process. Potentially, there could also be a lack of expertise on how to integrate anti-corruption measures into a process.

Using anti-corruption measures in a peace process comes with explicit restraints, particularly when the peace agreement, as a highly sensitive political document, may not be the ideal platform for extensive anti-corruption reforms. To navigate this, negotiators can defer the detailed initiatives to supplementary frameworks that allow for gradual, context-specific implementation. Implicit anti-corruption initiatives may be incorporated into peace agreements via larger structural reforms to promote transparency and good governance – which could boost accountability. The absence of the anti-corruption measures detailed above may be a result of the anti-corruption agenda being pushed down to the technical level or moved into other negotiation fora operating in parallel to the main political route. Alternative fora include the legislature, constitutional reform bodies, executive decisions, judicial decisions, and working groups which provide valuable pathways for incorporating anti-corruption reforms and mechanisms.

Underexplored entry points in peace agreements should be considered for further development. While references to anti-corruption measures are made, they often lack substance. It is important to find ways to translate general sentiments and expressed commitments into actionable steps. This can be achieved through various approaches, including collaboration with political elites, engaging at the technical level, and fostering grassroots support. To circumvent the politically fraught decision of whether to include anti-corruption measures or not, rhetorical commitments offer a compromise. However, as highlighted by a 2024 study on the Bangsamoro peace process in the Philippines, it is easy for rhetorical commitments in peace agreements to remain unimplemented when they are not effectively translated into actionable steps.b9a8b70ee26d

Minimal inclusion of anti-corruption measures within a peace process could be limited to:

- The signing, ratification and integration of UNCAC into domestic law

- Joining EITI and integrating the principles of transparency into local, regional, and state bodies, and enhancing the role of civil society in these processes.

- Reforming or establishing an independent commission focused on good governance – including provisions outlining its core operating principles in line with the 2012 Jakarta Principles.d1abb04f0fec Such a commission is also an opportunity for the inclusion of a 30-50% gender quota. In the meantime, establish an interim good governance commission with a clear timeline for establishing an independent commission, which shall ensure that the negotiated settlement adequately considers and addresses principals of good governance during implementation.

Each of the above items should include timeframes for implementation to ease their incorporation into subsequent implementation agreements and to monitor the implementation process.

Annex 1

Anti-corruption provisions in peace agreements

|

Category |

Code |

Agreements that include the category |

Percentage of total 2,055 agreements on PA-X Database |

|

Generic |

General commitment to anti-corruption |

48 |

2.3 |

|

Anti-corruption as a duty |

10 |

0.5 |

|

|

Roadmap |

17 |

0.8 |

|

|

Language of anti-corruption |

Terms for corruption/corrupt activities |

24 |

1.2 |

|

Concepts linked to corruption |

32 |

1.6 |

|

|

Consequences of corruption |

6 |

0.3 |

|

|

Reasons for corruption |

5 |

0.2 |

|

|

Substantive provisions/ implementation |

Commitment to transparency/disclosure |

38 |

1.8 |

|

Legal reform |

29 |

1.4 |

|

|

Enforcement/other bodies |

39 |

1.9 |

|

|

Enforcement/auditing body |

23 |

1.1 |

|

|

Enforcement/anti-corruption commission |

25 |

1.2 |

|

|

Enforcement/national budget |

11 |

0.5 |

|

|

Enforcement/self-regulation |

4 |

0.2 |

|

|

International law |

10 |

0.5 |

|

|

Third-party monitoring/assistance |

19 |

0.9 |

|

|

Safeguarding and whistleblowers |

6 |

0.3 |

|

|

Code of ethics |

15 |

0.7 |

|

|

Vetting public figures |

11 |

0.5 |

|

|

Disclosure of information/Freedom of Information laws |

13 |

0.6 |

|

|

Education, public awareness, training |

8 |

0.4 |

|

|

Conditional funding |

2 |

0.1 |

|

|

Substantive |

Dealing with past corruption and asset recovery |

11 |

0.5 |

|

Substantive/reform |

Civil service reform |

23 |

1.1 |

|

Private sector reform, including procurement regulations |

13 |

0.6 |

|

|

Security sector reform, including police, military, rebel groups |

14 |

0.7 |

|

|

Electoral reform (substantial) (not including generic ‘transparency in elections clauses’) |

11 |

0.5 |

|

|

Judicial reform |

12 |

0.6 |

|

|

Systemic reform (multisector and unspecified sector) |

23 |

0.8 |

|

|

Participation (general) |

21 |

0.7 |

|

|

Participation/gender |

16 |

0.4 |

|

|

Dealing with natural resources |

10 |

0.5 |

|

|

Dealing with illicit financial flows |

5 |

0.2 |

Annex 2

List of peace agreements including references to anti-corruption

|

Country |

Agreement name |

Date |

Peace process |

|

Afghanistan |

London Conference |

1 Feb 2006 |

Afghanistan: 2000s post-intervention process |

|

Paris Conference |

12 June 2008 |

||

|

London Conference Communique |

28 Jan 2010 |

||

|

The Resolution Adopted at the Conclusion of the National Consultative Peace Jirga |

6 June 2010 |

||

|

Renewed Commitment by the Afghan Government to the Kabul Conference Communique |

22 July 2010 |

||

|

Istanbul Process on Regional Security and Cooperation for a Secure and Stable Afghanistan |

2 Nov 2011 |

||

|

Bonn Conference |

5 Dec 2011 |

||

|

Tokyo Conference |

8 July 2012 |

||

|

Agreement between the two campaign teams regarding the structure of the national unity government |

21 Sept 2014 |

||

|

Algeria |

Plate-forme portant consensus national sur la période transitoire |

26 Jan 1994 |

Algeria: Bouteflika process |

|

Bahrain |

Bahrain National Dialogue Proposals, Executive Summary |

28 July 2011 |

Bahrain: Reform-based peace process |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina/ Yugoslavia |

Political agreement on principles for ensuring a functional Bosnia and Herzegovina that advances on the European path |

12 June 2022 |

Bosnia peace process |

|

Burundi |

Déclaration des partis politiques agrées et du gouvernement contre les fauteurs de guerre et en faveur de la paix et de la sécurité |

6 July 1994 |

Burundi: Arusha and related peace process |

|

Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi |

28 Aug 2000 |

||

|

Constitution de transition du 28 Octobre 2001 |

28 Oct 2001 |

||

|

Constitution of 18 March 2005 |

18 Mar 2005 |

||

|

Social contract between farmers and pastoralists in the commune Rugombo, Cibitoke province, Burundi |

23 Mar 2006 |

Burundi: Local process |

|

|

Cambodia |

Statement of the Five Permanent Members of the Security Council of the UN on Cambodia Incorporating the Framework for a Comprehensive Political Settlement of the Cambodia Conflict |

28 Aug 1990 |

Cambodian peace process |

|

Agreement on a Comprehensive Political Settlement of the Cambodia Conflict (Paris Accords) |

23 Oct 1991 |

||

|

Central African Republic (CAR) |

Bangui National Reconciliation Conference |

5 Mar 1998 |

CAR: Bangui process |

|

Transitional National Charter (Interim Constitution) |

18 July 2013 |

CAR: coups and rebellions process |

|

|

Pacte Républicain pour la paix, la réconciliation nationale et la reconstruction en la Républicain Centrafricaine |

11 May 2015 |

||

|

Synthesis of the Harmonised Claims of the Armed Groups of the RCO Bouar, of 30 August 2018 |

30 Aug 2018 |

CAR: African Initiative (and related) process |

|

|

Khartoum Accord |

5 Feb 2019 |

||

|

Chad |

Accord de paix entre le gouvernement de la République du Tchad et le Mouvement National (MN) |

25 July 2009 |

Chad: Fourth war process |

|

Colombia |

Acuerdo de 'Agenda Comun por el Cambio hacia una Nueva Colombia', Gobierno Nacional-FARC-EP |

6 May 1999 |

Colombia III – Arango |

|

Comunicado FARC-Gobierno del viaje a Europa, 23 de Febrero de 2000 |

23 Feb 2000 |

||

|

Comunicado FARC-Gobierno del viaje a Europa, 2 de Marzo de 2000 |

2 Mar 2000 |

||

|

Acuerdo sobre Reglamento para la Zona de Encuentro, Gobierno Nacional-ELN |

14 Dec 2000 |

||

|

General Agreement for the Termination of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace |

26 Aug 2012 |

Colombia V – Santos |

|

|

Participacíon política: Apertura democrá¡tica para construir la paz |

6 Nov 2013 |

||

|

Solucion al Problema de las Drogas Ilicitas |

16 May 2014 |

||

|

Agreement between National Government and ELN to establish peace talks in Colombia |

30 Mar 2016 |

||

|

Agreement on security guarantees |

23 June 2016 |

||

|

Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace |

24 Nov 2016 |

||

|

Acuerdo de Mexico |

10 Mar 2023 |

Colombia VI – Government-ELN post-2015 process |

|

|

Comoros/ (Anjouan) |

Accords d'Antananarivo |

23 Apr 1999 |

Comoros-Anjouan islands peace process |

|

Maroni Agreement |

20 Dec 2003 |

||

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

Linas-Marcoussis Agreement |

23 Jan 2003 |

Cote D'Ivoire: peace process |

|

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) |

Acte d'Engagement Gaborone |

24 Aug 2001 |

DRC: Second Congo War process |

|

Draft Constitution of the Transition |

1 Apr 2003 |

||

|

The Sun City Agreement |

2 Apr 2003 |

||

|

Accord Politique pour la gestion consensuelle de la transition |

19 Apr 2002 |

||

|

The Pretoria Agreement |

16 Dec 2002 |

||

|

Compte Rendu de la Rencontre Entre la Delegation du Gouvernement de la RDC Conduite par le Ministre de la Defence et la Delegation du Group Arme du Commandant Cobra Matata, en Presence de la MONUC a Aveba |

18 Nov 2006 |

DRC: Eastern DRC processes |

|

|

Declaration finale du forum sur la paix dans le territoire de Nyunzu |

10 Dec 2015 |

DRC: local agreements (East) |

|

|

Gabon |

Accord de Paris |

7 Oct 1994 |

Gabon peace process |

|

Guatemala |

Agreement on the Social and Economic Aspects and Agrarian Situation |

6 May 1996 |

Guatemala peace process |

|

Agreement on the Strengthening of Civilian Power and on the Role of the Armed Forces in a Democratic Society |

19 Sept 1996 |

||

|

Stockholm Agreement |

7 Dec 1996 |

||

|

India/ (Darjeeling) |

The Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (Amendment) Act 1994 |

28 Feb 1994 |

India-Darjeeling peace process |

|

India/ (Bodoland) |

Memorandum of Settlement on Bodoland Territorial Council |

10 Feb 2003 |

India Bodoland peace process |

|

Indonesia/ (Aceh) |

Third Meeting of the Joint Forum, Switzerland, 23–24 September 2000 |

24 Sept 2000 |

Indonesia-Aceh peace process |

|

Helsinki Memorandum of Understanding |

15 Aug 2005 |

||

|

Iraq/ (UN) |

Memorandum of Understanding between the Secretariat of the United Nations and the Government of Iraq on the Implementation of UNSC Resolution 986 |

20 May 1996 |

Iraq peace process – first Iraq war |

|

Memorandum of Understanding between the UN and the Republic of Iraq |

23 Feb 1998 |

||

|

Iraq |

Law of Administration for the State of Iraq for the Transitional Period |

8 Mar 2004 |

Iraq peace process – second Iraq war |

|

United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 1546 |

8 June 2004 |

||

|

Constitution of Iraq |

15 Oct 2005 |

||

|

Iraq/ (Kurds-Kurdistan) |

Erbil Agreement |

7 Nov 2010 |

Kurdistan/Iraq territorial conflict |

|

Ireland/ United Kingdom/ (Northern Ireland) |

New Decade, New Approach |

10 Jan 2020 |

Northern Ireland peace process |

|

Israel/ (Palestine) |

A Performance Based Roadmap to a Permanent Two-State Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict |

30 Apr 2003 |

Israel-Palestine peace process |

|

Kenya |

Kenyan National Dialogue and Reconciliation: Annotated Agenda and Timetable |

1 Feb 2008 |

Kenya peace process |

|

Kenyan National Dialogue and Reconciliation: How to Resolve the Political Crisis |

14 Feb 2008 |

||

|

Kenya National Dialogue and Reconciliation – Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission |

4 Mar 2008 |

||

|

Kenya National Dialogue and Reconciliation, Statement of Principles on Long-term Issues and Solutions |

23 May 2008 |

||

|

Resolutions of Peace and Cohesion Meeting of Leaders from Mt. Elgon Sub-counties, Bungoma, County: Abbey Resort Resolutions |

31 Mar 2015 |

Kenya local agreements |

|

|

Lebanon |

Memorandum of Understanding between Hezbollah and the Free Patriotic Movement |

6 Feb 2006 |

Lebanon peace process |

|

Lesotho |

The Electoral Pledge |

11 Dec 2014 |

Lesotho process |

|

Liberia |

Abuja Peace Agreement to Supplement the Cotonou and Akosombo |

19 Aug 1995 |

Liberia peace process |

|

Accra Agreement |

18 Aug 2003 |

||

|

Libya |

Libyan Political Agreement (Sukhairat Agreement) |

17 Dec 2015 |

Libyan peace process |

|

Palermo Conference for and with Libya, Conclusions |

13 Nov 2018 |

||

|

Roadmap for the Preparatory Phase of a Comprehensive Solution |

19 Nov 2020 |

||

|

The Second Berlin Conference on Libya |

23 June 2021 |

||

|

Declaration of the Paris International Conference for Libya |

12 Nov 2021 |

||

|

Reconciliation Charter between Tebu and Zway Tribes from Kufra |

20 Feb 2018 |

Libyan local processes |

|

|

Mali/ (Azawad) |

Accord Pour la Paix et la Reconciliation au Mali – Issu du Processus d'Alger |

20 June 2015 |

Mali-Azawad Inter-Azawad peace process |

|

Mozambique |

Declaração de Princíp ios sobre a despartidarização da Função Pública |

23 June 2015 |

Mozambique process – post-2012 Renamo insurgency |

|

Myanmar |

11-Point Common Position of Ethnic Resistance Organizations on Nationwide Ceasefire (Laiza Agreement) |

2 Nov 2013 |

Myanmar ceasefires process with ethnic armed groups |

|

The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement between the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the Ethnic Armed Organisations |

15 Oct 2015 |

||

|

Nepal |

25-Point Ceasefire Code of Conduct Agreed between the Government of Nepal and SPN (Maoist) |

25 May 2006 |

Nepal peace process |

|

Decisions of the Seven Party Alliance (SPA) – Maoist Summit Meeting |

8 Nov 2006 |

||

|

Comprehensive Agreement concluded between the Government of Nepal and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) |

21 Nov 2006 |

||

|

Nepal Interim Constitution |

15 Jan 2007 |

||

|

23-Point Agreement between the Top Leaders of the Seven-Party Alliance |

23 Dec 2007 |

||

|

Constitution of Nepal 2015 |

20 Sept 2015 |

||

|

Nigeria |

Kafanchan Peace Declaration, The Southern Kaduna State Inter-communal Dialogue |

23 Mar 2016 |

Nigeria – local agreements |

|

Nigeria/ (Plateau State) |

Declaration of Intent (by the Fulani Dialogue Steering Committee) |

19 May 2013 |

Nigeria – Plateau state process |

|

Declaration of Intent and Signatures |

10 July 2013 |

||

|

Pakistan/ (Taliban) |

Ahmadzai Wazir Wana Peace Agreement |

15 Apr 2007 |

Pakistan-Taliban process |

|

Papua New Guinea/ (Bougainville) |

Bougainville Peace Agreement |

30 Aug 2001 |

Bougainville: peace process |

|

Philippines/ (Mindanao) |

Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro |

15 Oct 2012 |

Philippines – Mindanao process |

|

The Independent Commission on Policing and its Terms of Reference |

27 Feb 2013 |

||

|

Rwanda |

Protocol of Agreement on Power-sharing within the Framework of broad-based Transitional Government between the Government of the Republic of Rwanda and the Rwandese Patriotic Front |

30 Oct 1992 |

Rwanda-RPF process |

|

Sierra Leone |

Abidjan Accord |

30 Nov 1996 |

Sierra Leone peace process |

|

Lomé Agreement |

7 July 1999 |

||

|

Somalia |

The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic |

29 Jan 2004 |

Somalia peace process |

|

Decision on the High-Level Committee, Djibouti Agreement |

25 Nov 2008 |

||

|

The Kampala Accord |

9 June 2011 |

||

|

Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia |

1 Aug 2012 |

||

|

Kampala Roadmap |

6 Sept 2011 |

||

|

Protocol Establishing the Technical Selection Committee |

22 June 2012 |

||

|

End of Transition Roadmap |

6 Aug 2012 |

||

|

Agreement between the Federal Government of Somalia and Jubba Delegation |

27 Aug 2013 |

||

|

Somalia/ (Puntland) |

Agreement between the Federal Government of Somalia and Puntland State of Somalia |

14 Oct 2014 |

|

|

South Africa |

National Peace Accord |

14 Sept 1991 |

South Africa peace process |

|

South African Constitution of 1993 (Interim Constitution) |

18 Nov 1993 |

||

|

South Sudan |

Yau Yau Agreement |

9 May 2014 |

South Sudan: Post-secession Local agreements |

|

Protocol on Agreed Principles on Transitional Arrangements Towards Resolution of the Crises in South Sudan |

25 Aug 2014 |

South Sudan post-secession process |

|

|

Framework for Intra-SPLM Dialogue |

20 Oct 2014 |

||

|

Arusha Agreement |

21 Jan 2015 |

||

|

Areas of Agreement on the Establishment of the Transitional Government of National unity (TGoNU) in the Republic of South Sudan |

1 Feb 2015 |

||

|

Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) |

17 Aug 2015 |

||

|

Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) |

12 Sept 2018 |

||

|

Rome Initiative for Political Dialogue in South Sudan, Declaration of Principles, 10 March 2021, Naivasha, Kenya |

10 Mar 2021 |

||

|

Waat Lou Nuer Covenant |

6 Nov 1999 |

South Sudan: pre-secession local peace processes |

|

|

South Sudan/ Sudan |

Outcome of the First Consultative Pankar Agreement |

20 Sept 2002 |

|

|

Outcome of the Second Pankar Consultative Meeting |

31 Oct 2002 |

||

|

Agreement on Permanent Ceasefire and Security Arrangements Implementation Modalities between the Government of Sudan and the SPLM/SPLA During the Pre-interim and Interim Periods |

31 Dec 2004 |

Sudanese (North-South) peace process |

|

|

Comprehensive Peace Agreement (Naivasha Agreement) |

9 Jan 2005 |

||

|

Agreement between the Government of Sudan and the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) (Cairo Agreement) |

18 June 2005 |

||

|

The Interim National Constitution of the Republic of Sudan 2005 |

6 July 2005 |

||

|

South Sudan/ Sudan/ (Darfur) |

Juba Declaration on Dialogue and National Consensus |

30 Sept 2009 |

|

|

Sri Lanka |

Sri Lanka Constitution Bill, an Act to Repeal and Replace the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka |

3 Aug 2000 |

Sri Lanka Kumaratunga/devolution processes |

|

The LTTE's Proposal for an Agreement to Establish an Interim Self-Governing Authority for the Northeast |

31 Oct 2003 |

Sri Lanka LTTE 2002 onward process |

|

|

Sudan |

Framework agreement between the Transitional Government of Sudan and the Darfur Track |

28 Dec 2019 |

Sudan transition process |

|

Juba Agreement |

3 Oct 2020 |

||

|

Draft Political Framework Agreement |

15 May 2022 |

||

|

Sudan/ (Darfur) |

Darfur Peace Agreement |

5 May 2006 |

Darfur-Sudan peace process |

|

Sudan/ (Eastern Sudan) |

Eastern Sudan Peace Agreement |

19 June 2006 |

Eastern Sudanese peace process |

|

Togo |

Dialogue Inter-Togolais: Accord Cadre de Lomé |

27 Sept 1999 |

Togo peace process |

|

Dialogue Inter-Togolais: Accord Politique Global |

20 Aug 2006 |

||

|

Tunisia |

Charte d'Honneur des Partis Politiques, des Coalitions et des Candidats Indépendants pour les élections et les référendums de la République Tunisienne |

22 July 2014 |

Tunisia reform process |

|

Yemen |

National Dialogue Conference Outcomes Document |

25 Jan 2014 |

Yemen peace process |

|

The Peace and National Partnership Agreement (PNPA) |

21 Sept 2014 |

||

|

Riyadh agreement between the legitimate Government of Yemen and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) |

5 Nov 2019 |

||

|

Zimbabwe |

Memorandum of Understanding between the Zimbabwe African National Union (Patriotic Front) and the two Movement for the Democratic Change Formations |

21 July 2008 |

Zimbabwe post-election process |

|

Agreement between the Zimbabwe African National Union-Global Political Agreement |

15 Sept 2008 |

||

|

Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 20) 2013 |

19 Mar 2013 |

- Haass and Ottmann 2017.

- PeaceRep 2024.

- Bell et al. 2024a, p. 11.

- IEP 2015.

- Rose-Ackerman 2008; Spector 2010, p. 416.

- Bell et al. 2024a.

- According to the World Bank, aspects that promote anti-corruption in peace processes include: improving public sector management; institutional restraints on power; increasing political accountability; increasing civil society participation; and the creation of a competitive economic sector (Boucher et al. 2007, p. 6.). Also see Forster 2020; Le Billon 2014, p. 770.

- An example is the Peace and National Partnership Agreement that formed a power-sharing government in bad faith between the Internationally Recognized Government of Yemen and the Houthi rebels (Ansar Allah) in 2014.

- Kovács 2024, p. 40.

- Bell et al. 2024a, p. 72.

- For an overview of coding, see Annex 1. Secondary coding removed 16 agreements not directly addressing anti-corruption, including references to criminal activities, trafficking of narcotics, smuggling, kidnapping, extortion and terrorism, as well as references to ‘transparency in elections’.

- Hegre and Nygård 2015.

- Amaya-Panche 2024.

- Spector 2012, p. 46; Lindberg and Orjuela 2014, p. 728; UNDP 2010.

- Sudanese (North-South) process, Liberia peace process, South African peace process, Iraq (second Gulf war) process, South Sudan (pre-secession local peace processes), Sudan transition process post-2019, Sri Lanka (Kumaratunga) process, Sierra Leone process, Lebanon peace process, Togo peace process, Kenya peace process, Mozambique de-partisanship process, Kurdistan process (Iraq).

- Rhetorical anti-corruption provisions appear in a limited capacity in inter-group (non-state) agreements from eight countries (Burundi, DRC, Kenya, Libya, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Sudan, and South Sudan/Sudan).

- Badanjak and Peter 2024, p. 36.

- Nigeria, Declaration of Intent (by the Fulani Dialogue Steering Committee), 15 May 2013.

- Nathan 2020.

- According to the coding category ‘language > terms for corruption’ (from 24 agreements), practices identified as corruption in peace agreements include: sabotage; embezzlement; waste and damage to public property; malevolence; defamation; fraud; malpractice; misappropriation; influence peddling; nepotism; favouritism; tribalism; regionalism; political patronage; clientelism; sexual harassment; bribery; abuse of power; forgery and deceitfulness; informal taxation; forceful collection of donations and financial support; creating a hurdle to legitimate development activities; and financial inducement.

- Nepal, Decisions of the Seven Party Alliance-Maoist Summit Meeting, 8 November 2006, p. 5.

- Bell and Forster 2020.

- Burundi, Social contract between farmers and pastoralists in the commune Rugombo, Cibitoke province, 23 March 2006, p. 3.

- Cote d’Ivoire, Linas-Marcoussis Agreement, 23 January 2003, p. 5.

- Afghanistan, London Conference Communique, 28 January 2010, p. 3; Yemen, National Dialogue Conference (NDC) Outcomes Document, 25 January 2014, p. 77.

- Guatemala, Agreement on Social and Economic Aspects and Agrarian Situation, 6 May 1996, p. 4.

- For instance, Colombia, Agreement on security guarantees, 23 June 2016, pp. 16-17.

- Mali, Accord Pour la Paix et la Réconciliation au Mali, 20 June 2015, p. 11.

- Sri Lanka, The LTTE’s Proposal for an Agreement to Establish an Interim Self-Governing Authority in for the Northeast, 31 October 2003, p. 4.

- Papua New Guinea, Bougainville Peace Agreement, 30 August 2001, p. 44.

- Afghanistan, Kabul Conference Communique, 22 July 2010, p. 3.

- However, a suggestion to include intelligence services is expected in Yemen, NDC Outcomes Document, 25 January 2014, p. 97.

- Yemen, The Peace and National Partnership Agreement, 21 September 2014, p. 2.

- Kenya, Kenya National Dialogue and Reconciliation – Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission, 4 March 2008, p. 1.

- Ireland/UK, New Decade, New Approach, 10 January 2020; Nepal, Constitution of Nepal, 20 September 2015, p. 99; Zimbabwe, Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (no. 20), 19 March 2013, pp. 100-101; Liberia, Accra Agreement, 18 March 2003, p. 12; DRC, Sun City Agreement, 2 April 2003, p. 72.

- Colombia, Final Agreement, 24 November 2016, p. 210.

- Sudan, Sudan Peace Agreement (Juba Agreement), 3 October 2020, p. 128.

- Iraq, Memorandum of Understanding between the Secretariat of the UN and the Gov. of Iraq on the implementation of UNSCR 986, 20 May 1996, p. 5.

- Somalia, Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia, 1 August 2012, 37; Sri Lanka, The LTTE’s Proposal for an Agreement to Establish an Interim Self-Governing Authority in for the Northeast, 31 October 2003, p. 4.

- Sudan, Darfur Peace Agreement, 5 May 2006, p. 42.

- Such as the International Contact Group on Liberia.

- South Sudan, ARCSS, 17 August 2015, p. 34.

- Aceh, Helsinki Memorandum of Understanding, 15 August 2005, p. 6.

- Afghanistan, London Conference Communique, 28 January 2010; Yemen, NDC Outcomes Document, pp. 80-82.

- Afghanistan, Tokyo Conference, 8 July 2012, p. 11.

- Boucher et al. 2007, x.

- Colombia, Participacíon Política : Apertura democrática para construir la paz, 6 November 2023, p. 15.

- Liberia, Accra Agreement, 18 August 2003, p. 9; DRC, Sun City Agreement, 2 April 2003; DRC, Accord Politique pour la gestion consensuelle de la transition en République Démocratique du Congo, 19 April 2002, p. 2.

- Colombia, Agreement on Security Guarantees, 23 June 2016, pp. 2-3.

- Sudan, Darfur Peace Agreement, 5 May 2006, p. 42.

- Somalia, Kampala Roadmap, 6 September 2011, 11; Liberia, Accra Agreement, 18 August 2003, p. 12.

- Rwanda, Protocol of Agreement on Power-sharing, 30 October 1992, p. 14.

- South Sudan/Sudan. Outcome of the First Consultative Pankar Agreement, 20 September 2002, p. 20.

- Hopp-Nishanka, Rogers, and Humphreys 2022, p. 25.

- Kovács 2024.

- Clarified by UNODC 2020.